WHEN British soldiers memorably climbed out of their trenches on the Western Front over Christmas 1914 and fraternised with the Germans in an unofficial truce, a few among them could claim a certain distinction.

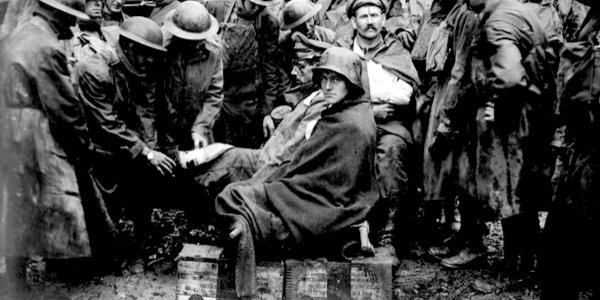

They were the original members of the British Expeditionary Force who were sent to France on the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914 – the men who would go down in history as the Old Contemptibles. Tragically, by late December, most of them had been annihilated.

Those losses 110 years ago should perhaps concentrate today’s military minds after the statement earlier this month by Alistair Carns, the Minister for Veterans, that the entire current British Army would be wiped out in ‘six months to a year’ during a major war.

After Britain entered the war on August 4, 1914, the four infantry divisions and one cavalry division that comprised the BEF were dispatched across the Channel under the command of General John French to help repel the Germans who were threatening to overrun northern France.

With an initial complement of about 80,000-90,000, the force was marginally larger than the whole of today’s British Army, which consists of only around 72,000 trained soldiers ready for deployment, the smallest number since the Napoleonic Wars.

The men of the BEF were seasoned regulars, some of them veterans of the Boer War of 1899-1902, where invaluable lessons had been learned about tactics and deployment. They were armed with magazine-fed Lee Enfield rifles, and highly trained in using them to deliver accurate, rapid fire. They would prove formidable weapons and fighters.

The German Kaiser, Wilhelm III, unwittingly gave these soldiers their name when he reportedly issued an order on August 19 telling his commanders: ‘It is my royal and imperial command that you concentrate your energies, for the immediate present, upon one single purpose, and that is that you address all your skill and all the valour of my soldiers to exterminate first the treacherous English and walk over General French’s contemptible little army.’

What exactly the Kaiser meant, or whether he even said it, remains controversial. But to veterans, the words were a badge of honour and after the war they took to calling themselves the Old Contemptibles.

But that was yet to come. By the end of 1914, after a series of bruising battles, thousands of the irreplaceable professionals who had marched out with the BEF that summer were dead or wounded. By the autumn, reinforcements massively boosted the British forces, but as Christmas approached, the original warriors had almost been wiped out.

However, by then the old sweats of the BEF had done their bit in blunting the steamroller advance of the German armies and helping save France from total defeat. Their finest hour came at Mons on August 23, where the rifle fire of the battalions dug in along the Canal du Centre devastated the German attackers. A British soldier was trained to hit a man-sized target 15 times a minute at a range of 300 yards with his Lee Enfield and the Germans reportedly thought they were being by assailed by machine guns.

But the respite was only brief. After Mons, the BEF had to join the French in a 200-mile fighting retreat southwards, punctuated by costly clashes with the enemy, until in September the Germans were halted and thrown back in the Battle of the Marne outside Paris. By late November, the British had made their way north to Ypres, where they stood fast, and the war became the trench stalemate that was to last until 1918.

Parallels between the BEF and the situation in today’s British Army only go so far, of course. But it is a sobering thought that the whole of our land-based fighting forces could simply be obliterated in a short time – and, unlike in 1914, there would be no mass armies of volunteers or conscripts ready to replace them.

On an uplifting footnote, it is heartening to read the story of Scotsman Alfred Anderson, who served with the Black Watch in France from November 1914. He was the last surviving Old Contemptible and the last surviving participant in the Christmas Truce. He died in November 2005 at the age of 109.

About the truce, Alfred recalled: ‘All I’d heard for two months in the trenches was the hissing, cracking and whining of bullets in flight, machine-gun fire and distant German voices. But there was a dead silence that morning, right across the land as far as you could see. We shouted “Merry Christmas”, even though nobody felt merry. The silence ended early in the afternoon and the killing started again. It was a short peace in a terrible war.’