Professional historians have no special expertise. In the study of the past, there is no difference between a professional and an amateur historian. If they put their minds to the task, even untutored undergraduates might discover a more profound truth about the past than their learned professor, the limits of their knowledge notwithstanding.

Historians All!

What was Carl Becker thinking? When, on December 29, 1931, Becker delivered the presidential address to the annual meeting of the American Historical Association, he was already something of a controversial or, perhaps more accurately, an enigmatic, figure.[i] Having studied as an undergraduate with Frederick Jackson Turner at the University of Wisconsin and having completed a doctorate at Columbia under the supervision of James Harvey Robinson, Becker was among the proponents of the “New History.” Some members of his audience undoubtedly regarded him as a skeptic and a relativist who denied the possibility of absolute, objective truth. Others saw him as a populist who extolled the common man and castigated the elite.[ii]

An iconoclast, or at least a nonconformist, Becker rejected the conviction that history was a science. He doubted that historians need only to accumulate and arrange the facts to produce an exact transcript of the past. In his own diverse scholarship, he asked penetrating questions but seemed always to be unsatisfied with the answers. He was never quite sure of anything. “No doubt throughout all past time,” he wrote:

there actually occurred a series of events which, whether we know it was or not, constitutes history in some ultimate sense. Nevertheless, much the greater part of these events we can know only imperfectly; and even the few events that we think we know for sure we can never be absolutely certain of, since we can never revive them, never observe or test them directly. The event itself once occurred, but as an actual event it has disappeared; so that in dealing with it the only objective reality we can observe or test is some material trace which the event has left–usually a written document.[iii]

Historians perforce viewed the past only at a distance, their vision at once clarified and obscured by documents that always required interpretation. In his presidential address, Becker thus challenged the prevailing orthodoxies of the history profession, chief among them the belief that objectivity was viable and the confidence that facts spoke for themselves to yield unassailable truth.[iv]

Whatever else he may have been, Becker was also a trickster, a persona never more evident than in “Everyman His Own Historian.” Becker lulls his audience into a comfortable familiarity with a character whom they think they already know: an ordinary man living an ordinary life and doing ordinary things such as paying his debts. Mr. Everyman is troubled by the nagging feeling that he has forgotten a matter of some importance. When memory fails him, he consults his archive of personal records to discover that he must pay for the coal he has purchased to keep his home warm during the winter. It turns out that not only is his memory faulty, but his records are also mistaken. When he arrives at the offices of Mr. Smith to settle the account, Smith informs him that, in fact, Everyman owes Mr. Brown, for Brown had the kind of coal that Everyman wanted. Smith passed the order on to his competitor. Mr. Everyman then goes to Brown’s office to pay what he owes.

Becker concludes that to get through life and to solve the problems that confront him, Mr. Everyman has done historical research and continued to refine his analysis until he uncovered a truth that worked for him. He owes Brown, not Smith. Mr. Everyman is his own pragmatic historian. He identified a problem. He did the research, both by reviewing documents and conducting oral history interviews, to find the information that enabled him to answer his questions. He then took the course of action that the information indicated was prudent. He paid Brown.

But Becker’s account is disturbingly simple. His description of the process of discovering truth and meaning in history belies his objection to the idea that history is a science. The apparent representative of the common American during the early 1930s, Mr. Everyman owes $1,017.20 for the purchase of twenty tons of coal. These figures are preposterous.The first indication of trouble is that twenty tons is an enormous amount of coal, more than anyone could ever store let alone use. Unless Mr. Everyman lived in a castle, which would disqualify him as an ordinary American, he bought far more coal than he needed. In addition, the coal he purchased was too expensive. In 1931, the going rate for a ton of coal was $13, which included the cost of delivery. Unless Brown had criminally inflated his prices, even had Mr. Everyman bought twenty tons of coal, he ought to have paid only $260 for it. Instead he paid $50.86 per ton. Why would a reasonable man ever agree to such a price, especially when the average annual income in 1931 was $1,850? According to the figures that Becker supplies, Mr. Everyman spent 54.9 percent of his annual income on coal. To have engaged in such a transaction would constitute economic madness, unless, unlike most of his fellow Americans in 1931, Mr. Everyman literally had money to burn.

Becker seems to be enjoying a good joke at our expense. Surely his audience at the annual meeting of the American Historical Association knew that his figures were exaggerated and that the exaggeration was deliberate. I, by contrast, had to do research to determine the cost of coal, the average annual income, and the amount of coal that a homeowner would buy to see his family through the winter. As a consequence, I return to my original question: what was Carl Becker thinking? In all candor, I do not know. Was Becker intellectually perverse? Was he merely toying with us? Alternately, was he illustrating an important point about the nature of historical facts? Caveat lector.

Although Becker explains all the pertinent facts about Mr. Everyman’s situation, he leaves a distorted image of reality. The facts that he presents are themselves at best inaccurate and at worst false. Having begun my inquiry, it was comparatively easy to find out the price of coal and the average annual income in 1931. It was harder, first, to know that I needed to verify Becker’s figures and, second, to establish the context that gave the facts meaning. Becker acknowledged that “every generation, our own included, will, must inevitably, understand the past and anticipate the future in light of its own restricted experience.”[v] I have no experience ordering coal. I have no idea what various items cost in 1931. My experience is restricted. Although I could examine the vast historical record to learn more than I had from experience alone, I would have been embarrassingly mistaken in my conclusions were I to accept without question the information that I found. I could have accumulated a series of facts and still misinterpreted the past.

At times, Becker pulls back the veil and hints at the method that guides his madness. Mr. Everyman has a utilitarian and instrumentalist view of history, which enables him to make sense of experience, to function in society, and to maintain a coherent identity. Such matters are hardly trivial, as Becker made clear:

In the realm of affairs Mr. Everyman had been paying his coal bill; in the realm of consciousness he had been doing that fundamental thing which enables man alone to have, properly speaking, a history: he had been reinforcing and encircling his immediate perceptions to the end that he may live in a world of semblance more spacious and satisfying than is to be found in the narrow confines of the fleeting present…. Without historical knowledge… his to-day would be aimless and his to-morrow without significance.[vi]

But as his own historian, Mr. Everyman“takes facts as they come to him, and is enamored of those that seem best suited to his interests or promise most in the way of emotional satisfaction.” He respects the “cold, hard facts, never suspecting how malleable they are, how easy it is to coax and cajole them.”[vii] Mr. Everyman wants a history that works to serve his immediate purposes. History is only important to him because it is useful. He ought perhaps to have been more circumspect, reflecting that there are more things in heaven and on earth than were dreamt of in his philosophy.

Becker recognized the democratization of historical thinking that had taken place during the twentieth century. Like his contemporary, the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga, Becker understood that modern men and women had become historians by nature. People understood themselves and their world by investigating the past. “Historical thinking has entered our very blood,” Huzinga asserted.[viii] Mr. Everyman’s sense of the past orients him in the present, and prepares him as much as possible for the future. It had become impossible for him “to divorce history from life.”[ix] The past for Everyman was not dead. It was, in fact, as Becker declared, intimately connected to the life of the present and the future:

Running hand in hand with the anticipation of things to be said and done, enables us, each to the extent of his knowledge and imagination, to be intelligent, to push back the narrow confines of the fleeting present moment so that what we are doing may be judged in the light of what we have done and what we hope to do. In this sense a living history, as Croce says, is contemporaneous; in so far as we think the past…, it becomes an integral and living part of our present world of semblance.[x]

Surely Becker also knew that the title of his address paraphrased Martin Luther’s famous declaration “every man his own priest.” In the sixteenth century, Luther intended to defy the exclusive authority of the Roman Catholic Church to interpret scripture and thereby to control the spiritual lives of the faithful. He lived to regret his pronouncement. It led to all manner of interpretations of scripture and diverse expressions of faith, most of which horrified Luther, who knew religious and spiritual anarchy when he saw it.

Becker tried to forestall the rise of similar chaos by positing two visions of history. Actual History consisted of events that had taken place in the past but that no longer existed. Ideal history is the past that human beings remember, affirm, and interpret. If Actual History is absolute and unchanging—“It was what it was whatever we do or say about it,” Becker conceded—Ideal History was subject to numerous interpretations. The past is fixed. The understanding of the past is variable. It changes in response of the increase in or refinement of knowledge, or the altered perspectives, concerns, and values that historians bring to their inquiries. Becker never seems to have question whether the world, past and present, was real, but portions of it existed separately from what human beings could know. Historians must do their best to make Ideal History correspond as closely as possible to Actual History. They must, in other words, strive to find the truth, or at least to eliminate what is not true. Yet, because Ideal History is intimately connected to life in the present, because it is a living entity, it cannot be static.”History in this sense,” Becker argued, “can not [sic] be reduced to a verifiable set of statistics [as in the account of Mr. Everyman’s coal purchase] formulated in terms of universally valid mathematical formulas. It is rather an imaginative creation, a personal possession which each of us… fashions out of his individual experience, adapts to his practical or emotional needs, and adorns as well as may be to suit his aesthetic tastes.”[xi] The mind constructs reality, although reality itself is no mere construct.

Historians thus carry out the imaginative reconstruction of vanished events that took place in a lost world according to the needs and purposes of their time. They must strive to establish the facts with as much accuracy as possible but should never assume, as did the scientific historians of the nineteenth century, that their interpretations are definitive or that the facts speak for themselves. For Becker, the facts per se did not even exist. It is not “the undiscriminated fact, but the perceiving mind of the historian that speaks.”[xii] Needs and purposes change. Each generation rewrites history anew. From the epistemological deficiencies of scientific history emerged the need for such historical judgment and revision, which, however imprecise and incomplete, was often more insightful and profound than the facile conclusions of scientific historians. Abandoning the pretense of objectivity and omniscience, historians, in Becker’s view, must accept their own fallibility. They must become critically introspective, reminding themselves never to be too certain of anything.[xiii]

The value of history remained undiminished even though historians did not and could not provide an exact transcript of the past. That all historical conclusions were speculative, provisional, and limited, Becker maintained, only reflected the complex and variable nature of reality itself . “Regarded historically, as a process of becoming,” he pointed out, “man and his world can obviously be understood only tentatively, since it [sic] is by definition something still in the making, something as yet unfinished.”[xiv] Truth there is, but in Becker’s estimation the truth that human beings can know is neither complete nor final. “I have no faith in the infallibility of any man, or of any group of men, or of the doctrines or dogmas of any man or group of men,” he said, “except in so far as they can stand the test of free criticism and analysis. I agree with Pascal that ‘thought makes the dignity of man’; and I believe therefore that all the great and permanently valuable achievements of civilization have been won by the free play of intelligence in opposition to, or in spite of, the pressure of mass emotion and the effort of organized authority to enforce conformity in conduct and opinion.”[xv] Becker’s skepticism offers an essential corrective to an age rife with factionalism–an age propelled by the assurances of intellectual fanaticism and moral absolutism. But is the skeptical attitude of mind that Becker exemplified sufficient to an age that also seeks affirmation and hope?

The Quest for Reality

Human beings do not live by doubt alone. The accumulation and refinement of historical knowledge on some level ought to yield greater understanding of the past and bring greater clarity to life. As Becker insisted, “one of the first duties of man is not to be duped, to be aware of his world; and to derive the significance of human experience from events that never occurred is surely an enterprise of doubtful value.”[xvi] Historians should thus work tirelessly to identify the facts. But to think that such knowledge is the product of a neutral and objective inquiry into the evidence rather than an intellectual construct is to embark on a fool’s errand. By the 1960s and 1970s, critics of objectivity had far exceeded Becker’s admonition. Although seemingly impartial, historians, they alleged, did not seek the truth but instead, perhaps unwittingly, expressed their own prejudices, beliefs, interests and commitments. Hardly a category of thought or a form of knowledge, history was at best no more than another literary genre, an elaborate fiction advertised as reality.[xvii]

This critique had the benefit of exposing the often arbitrary ways in which human beings accumulate information and generate knowledge, and the mechanisms by which some information and knowledge comes to be accepted, valued, and privileged. It further illustrated how language itself shaped consciousness and determined reality, liberating the study of history once and for all from the dictates of positivism. At the same time, it rendered “meaning” and “truth” not merely subjective but also solipsistic. Like all human beings, historians were the prisoners of their own categories of thought and their own systems of communication. Neither omniscient nor authoritative, historians could know nothing beyond the discourse that they had created and in which they were fully immersed. Reality as such was purely conceptual, no more than an elaborate fiction. It did not exist outside the mind.

This effort to think about thinking has been indispensable to understanding the past and the present, our ancestors and ourselves, and the world, both inherited and made. Confronting the limits of our knowledge should chasten and humble us, but should also reveal how our methods of gathering, organizing, and authenticating knowledge may distort rather than focus our vision. Yet, however much the rejection of objectivity provided a salutary check on intellectual arrogance, it also constituted another form of determinism, a new absolutism, that categorically denied to historians, along with everyone else, the capacity to think beyond their own interests and identities.

To disavow the validity of objective truth does not entail a simultaneous denial of reality. The critics of objectivity went too far. Insisting that reality does not exist outside the mind, they contended that knowledge, understanding, and communication are impossible. Most historians, by contrast, have long known that language is artificial and imperfect. But language is not arbitrary. Its significance and utility rest on a set of conventions. Even as language changes over time, the people who use it in writing and speech develop a consensus of meaning that permits them to communicate with one another. Although no precise correspondence exists between reality and the words we use to describe it, language arises from human contact with the world. Human beings use language to make sense of a reality that exists outside the self. We “clothe thought in words,” as Jacob Burckhardt attested.[xviii] This act is no mere discourse on discourses. The imperfect knowledge of something, and the inadequate means available to discuss it, does not negate its existence. [xix]

By itself, without attention from historians, the past is inert. Only when historians begin to ask questions about the past does it come alive in the present. Knowledge originates in the mind. As Becker stated, “the historical facts lying dead in the records can do nothing good or evil in the world. They become historical facts, capable of doing work, of making a difference, only when someone, you or I, bring them alive in our minds by means of pictures, images, or ideas of the actual occurrence. For this reason I say that the historical fact is in someone’s mind, or it is nowhere….”[xx] Implied in Becker’s commentary is also the recognition that knowledge begins with a subject whose perspective is neither dispassionate nor transcendent. Knowledge is not objective or subjective. It is personal. “The historian,” Becker contended, “cannot eliminate the personal equation.”[xxi] An interactive relation exists between the knower and the thing known; subject and object are intertwined and inseparable.

Objectivity in history, as in every other human endeavor, is impossible, even if it were desirable. No account of the past is, or can be, impartial and definitive. When applied to history, the illusion of objectivity means that knowledge and truth exist outside the mind. If such were the case then different historians would inevitably and invariably arrive at the same conclusions, which would also be the only conclusions that it was possible for them to reach. The subjectivist attack on objectivity is preferable, but still marred by its own species of determinism. The English historian and philosopher R.G. Collingwood, for example, appreciated that different historians writing at different times,in different places, and under different circumstances would fashion different interpretations of the past. For historical inquiry takes place in the mind of the historian and nowhere else. “How does the historian discern the thoughts which he is trying to discover?” Collingwood asked. “There is only one way in which it can be done: by re-thinking them in his own mind.” He elaborated:

It may thus be said that historical inquiry reveals to the historian the powers of his own mind. Since all he can know historically is thoughts that he can re-think for himself, the fact of his coming to know them shows him that his mind is able… to think in these ways. And conversely,whenever he finds certain historical matters unintelligible, he has discovered a limitation of his own mind; he has discovered that there are certain ways in which he is not, or no longer, or not yet, able to think. Certain historians, sometimes whole generations of historians, find in certain periods of history nothing intelligible, and call them dark ages; but such phrases tell us nothing about those ages themselves, though they tell us a great deal about the persons who use them, namely that they are unable to re-think the thoughts which were fundamental to their life.[xxii]

Notwithstanding Collingwood’s admirable formulation that the past comes to life, or not, only in the minds of historians, and that different historians were bound to see the past from different angles of vision, he assumed that they could not escape their own time, place, and circumstances. Augustine of Hippo, an African and early Christian, Louis-Sébastien Le Nain de Tillemont, a seventeenth-century Frenchman, Edward Gibbon, an eighteenth-century Englishman, and Theodor Mommsen, a nineteenth-century German, each had a distinctive interpretation of Roman history. “There is no point in asking which was the right point of view,” Collingwood observed. “Each was the only one possible for the man who adopted it.”[xxiii] It is imperative that historians admit the historicity of their thought by clarifying its sources, nature, purposes, and limitations. It is quite another matter to presume that historians cannot liberate themselves from their environments and their identities, and are thus constrained only and ever to think as they do.

Ironically, René Descartes, the thinker most responsible for the dichotomy between subject and object, may also have effected one of the most significant advances in human consciousness. A mathematician, Descartes was principally interested in the external structure of the world. He invented a method that he called “geometrical calculus” (calcul géométrique) by which he applied algebraic equations and formulas to the problems of geometry. Although he gave scant and rather feeble attention to the workings of the mind, his celebrated formulation cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore, I am) established mind as an integral component of reality.“From the very fact that I know with certainty that I exist,” Descartes began, “and that I find that absolutely nothing else belongs necessarily to my nature or essence except that I am a thinking being, I readily conclude that my essence consists solely in being a body which thinks or a substance whose whole essence or nature is only to think.”[xxiv] As thinking creatures, Descartes implied, human beings knew and understood the world as much from the inside out as from the outside in.

The historian John Lukacs confirmed Descartes’s intuition–an intuition that Descartes himself almost completely disregarded. “As in the advancing life of a person,” Lukacs wrote, “we have learned (or at least should have learned) more and more about ourselves. This is what the evolution of historical consciousness is all about; but we must recognize that our experience and knowledge of the outside world, too, comes from the inside: it is we who are doing the knowing and the thinking, we are the knowers, with all of our limitations.”[xxv] Like life, thinking required persistent concentration, intellectual discipline, and active engagement. Knowledge was not wholly objective nor was reality wholly external. Interior reflection–thinking–was essential both to understanding the world and to validating the existence of the self. The way to reality, even for Descartes, lay in and through the mind.

Everyone has their biases, preferences, and aversions. Yet, having cast off objectivity, human beings must retain the ability to distinguish fact from fiction, truth from falsehood. Interpretations of reality, past and present, must be verifiable, even when contested. Evidence must be accessible so that historians may question, confirm, refine, modify, or eliminate the interpretations of others. It would thus be a grave error to dispose of the scientific method altogether and to try to restore a premodern, prescientific world view that stunted critical analysis. The Spanish philosopher Julian Marías affirmed that in the modern world–the very designation “modern” suggests the evolution of historical consciousness–such a perspective was, in fact, indispensable:

We cannot understand the meaning of what a man says unless we know when he said it and when he lived. Until quite recently, one could read a book or contemplate a painting without knowing the exact period during which it was brought into being. Many such works were held up as “timeless”models beyond all chronological servitude. Today, however, all undated reality seems vague and invalid, having the insubstantial form of a ghost.[xxvi]

Ideas and insights, concepts and theories are fragile and susceptible to change. Historians writing at different times are almost certain to interpret the past differently than those who came before them. Successive generations do not so much revise or discard older views as they reinvest the past with contemporary significance. In each case no one knows the whole of the past, but the past is all anyone knows.

Critics, many of whom reject the competence of experts and the value of expertise, tend to regard the frequent reassessment of the past, just as they do the revision of scientific findings, with disdain.[xxvii] Such modifications seem to invalidate all research and scholarship, confirming the relativism and subjectivity of historical judgments by reducing them, at best, to mere opinion. But truth is rarely static. There are moments of truth, which may pass away or lose their importance. By the same token, truth is rarely singular or unitary. There is a multiplicity of truth. It is, as Lukacs has shown, through “re-thinking” rather than “re-search” that historians again bring the past to life.[xxviii] New versions of familiar narratives are not exercises in intellectual hubris or caprice. The imaginative reenactment of the past results instead from the accumulation of knowledge and experience that, over time, deepen and enrich human consciousness.[xxix] For the purpose of knowledge is not certainty but understanding and, perhaps, if we are fortunate, illumination.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[i] Carl Becker, “Everyman His Own Historian” (Washington, D.C., 2009).

[ii] Later generations, inaccurately I think, came to view, and sometimes to condemn, Becker as the harbinger of post-modernism who denied not only the existence of objective truth but also of any reality outside of a constructed literary discourse. Yet, Becker did write that “the form and substance of historical facts, having a negotiable existence only in literary discourse, vary with the words employed to convey them.” Becker, “Everyman,” 17.

[iii] Ibid., 5.

[iv] See Peter Novick, That Noble Dream: The “Objectivity Question” and the American Historical Profession (Cambridge, U.K., 1988).

[v] Becker, “Everyman,” 18.

[vi] Ibid., 10, 7.

[vii] Ibid., 14.

[viii] Johan Huizinga, “The Idea of History,” in Fritz Stern, ed., The Varieties of History (New York, 1973), 303.

[ix] Becker, “Everyman,” 11

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid., 12. See also Carl L Becker, “What Are Historical Facts?,” The Western Political Quarterly 8/3 (September 1955), 327-40.

[xii] Ibid., 17. See also Carl Becker, “Detachment and the Writing of History,” The Atlantic Monthly 106 (October 1910), 524-36.

[xiii] To his credit, Becker exposed ideas that he approved as well as those he opposed to the same critical skepticism and analysis. See, for example, his review of James Harvey Robinson’s New History in The Dial 53 (1 July 1912), 21. See also Robert Allen Skotheim, American Intellectual Histories and Historians (Princeton, NJ, 1966), 80.

[xiv] Becker, “Everyman,” 19.

[xv] Quoted in “Carl Becker: In Memoriam,” American Historical Review 50/4 (July 1945) . Becker’s skepticism had only a negligible effect on the history profession until after the First World War. Following the Second World War, many historians attacked, rejected, or ignored his epistemology. See, for example, Chester McArthur Destler, “Some Observations on Contemporary Historical Theory, American Historical Review 55/3 (April 1950), 503-29. Destler’s essay was subsequently reprinted as “The Crocean Origins of Becker’s Historical Relativism,” History and Theory 9 (1970), 334-42; Perez Zagorin, “Carl Becker on History: Professor Becker’s Two Histories: A Skeptical Fallacy,” American Historical Review 62/1 (October 1956), 1-11. For a more extensive discussion and analysis of the debate, see Novick, That Noble Dream, 105-107, 400-405.

[xvi] Becker, “Everyman,”16.

[xvii] For additional discussion, see Lorraine Daston and Peter Gailson, “The Image of Objectivity,” Representations 40 (Fall 1992), 81-128. This criticism ironically reduces history again to a branch of literature, the very identity that scientific history arose to discredit and overcome.

[xviii] Jacob Burkhardt, “The Three Powers,”in Reflections on History (Indianapolis, IN, 1979), 94.

[xix] See John Lukacs, Historical Consciousness: The Remembered Past (New Brunswick, 1994), 108-14.

[xx] Becker, “What Are Historical Facts?,” 332.

[xxi] Ibid., 335.

[xxii] R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (London, 1977), 215, 219.

[xxiii] Quoted in T.M. Knox, Editor’s Preface to The Idea of History, xii.

[xxiv] René Descartes, Discourse on Method and Meditations, trans. by Laurence J. Lafleur (Indianapolis, IN, 1960), 132.

[xxv] Lukacs, Historical Consciousness, 346.

[xxvi] Julian Marías, Generations: A Historical Method (Tuscaloosa, AL, 1972), 178.

[xxvii] I feel constrained to add that the skepticism about experts and expertise is both healthy and dangerous. For more than thirty years, I told my students that the nature and quality of their thinking about the past was not fundamentally different from mine. Except for my more extensive knowledge of the past and my more complete understanding of how to write history and document my research, the process of my thinking about the past was identical with theirs. Most did not believe me or understand the point I was making.

Professional historians have no special expertise. In the study of the past, there is no difference between a professional and an amateur historian. If they put their minds to the task, even untutored undergraduates might discover a more profound truth about the past than their learned professor, the limits of their knowledge notwithstanding. My courses were predicated on disabusing students of the conviction that they should repeat to me what they thought I wanted to them to say and persuading them instead to tell me what they saw and understood, especially if they made the effort to enter the world of the past in thought and imagination and not simply to see it as a dim replica of their own. No one ought to be surprised that, as a teacher, I was a miserable failure.

The danger arises, in part, from the notion, which many of the students whom I taught believed, that knowledge and wisdom are illusory, and that what passes for instruction is deceptive and fraudulent. No one really knows anything about anything. As such, no one has the right or the authority to judge the ideas and conclusions of others. Those who sit in judgment only have the power to do so–a power that institutions and bureaucracies confer on them and that is thus illegitimate, arbitrary, and unjust.

[xxviii] Lukacs, Historical Consciousness, 328, n. 6. Italics in the original.

[xxix] On the contrary, should human beings forget, or should they cease to recognize or understand, what they once knew, it may be because their minds have grown lazy and shallow, because they have become indifferent or distracted, or because previous knowledge has become irrelevant to them, no longer addressing their needs or enabling them to solve their problems. See, for example, the discussion in Owen Barfield, History, Guilt, and Habit (Middleton, CT, 1981), 74.

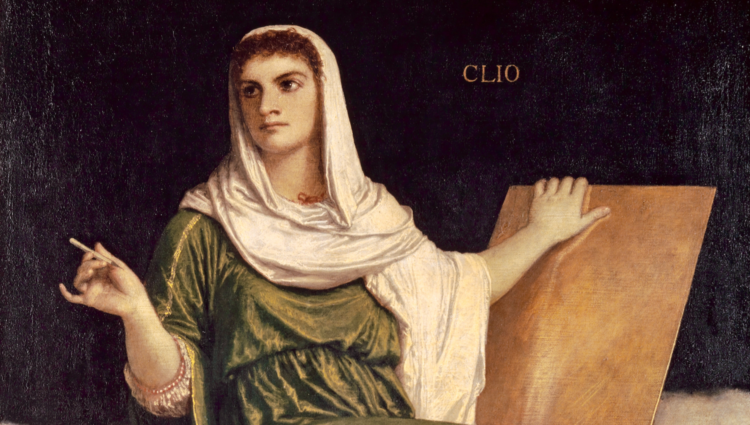

The featured image is “Clio” (1875), by Arnold Böcklin, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.