IT’S THE same every time a bit of windy weather comes along, isn’t it? Storm Eowyn brought out the usual hysterical reporting, being described as ‘record-breaking’, ‘once-in-a-generation’ and ‘battering the UK with hurricane-force winds’.

Needless to say, none of these claims was true.

The Irish Met Office said Eowyn’s winds of 114mph set a record for Ireland, beating the 113mph recorded in 1945 and 1961. (During the 1945 storm, the measuring equipment reached 113mph before it broke, almost certainly meaning wind speeds were higher still.)

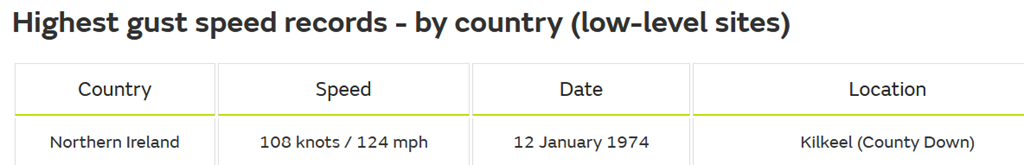

Unfortunately they were lying, because winds of 124mph were recorded at Kilkeel in Northern Ireland in 1974:

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/maps-and-data/uk-climate-extremes

That same storm in 1974 also brought much stronger winds to most of Britain than anything seen last week, including 97mph at Eskdalemuir, 83mph at Ringway and 94mph in the Scillies.

The headline event trumpeted by the Met Office during Eowyn was the declaration of 100mph winds at Drumalbin in Scotland. However, as we have now become thoroughly accustomed to, this was measured on top of an 800ft hill in the middle of the windswept Lanarkshire Hills. The Met Office started recording winds there only some time after 1994.

It was this that led to wildly inaccurate headlines of ‘100mph winds sweeping the country’.

It is now the standard practice of the Met Office to use locations on exposed clifftops and hilltops to advertise the windiest places. They are all automatic stations set up since 1990, so none appears in the older archives, which typically list representative sites where people actually live.

While Drumalbin’s hilltop saw 100mph winds, other places in Scotland and Northern Ireland typically did not get above 80mph. This was the part of the country which Eowyn hit the hardest. Still very windy, of course, but no more than the sort of storm we see every few years. You don’t even have to look hard to find examples. Eighty years ago to the month, for instance, a storm brought 113mph winds to Pembrokeshire (the same speed as those 113mph+ winds in Limerick which broke the equipment!).

Storms in 1969, 1989 and 1990 each set records in Scotland, with wind speeds much higher than Eowyn:

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/maps-and-data/uk-climate-extremes

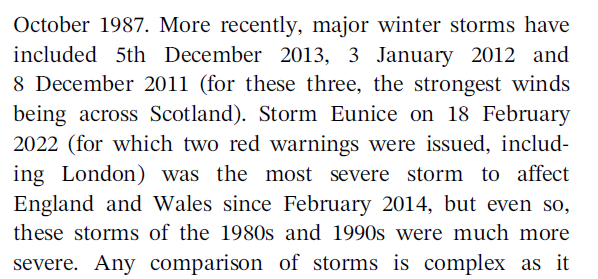

The Met Office at least brought a hint of reality when they said it was the strongest storm in ten years. But even that does not stand up to scrutiny as Eunice brought stronger winds three years ago, with 122mph measured on the Needles, another clifftop site on the Isle of Wight, in 1996. More to the point, Eunice itself was not unusually powerful, as the Met Office State of the Climate Report last year revealed:

https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/joc.8553

Indeed it is this relative absence of really strong storms in the last decade or so which made Eowyn seem ‘exceptional’. It is well known that those 1980s and 90s storms were at another level – not only the Great Storm of 1987, but also Burns Day in 1991, the Braer Storm in 1993 and the Boxing Day storm in 1998. To call Eowyn ‘once in a generation’ is an insult to all those who suffered then.

The claim that Eowyn brought ‘hurricane-force winds’ is a total misunderstanding of how hurricanes are categorised. According to the official Saffir-Simpson scale, a storm has to be at least 74mph before it can be categorised as a hurricane. But, crucially, this is measured as an average, sustained speed over one minute, not just a gust speed, which is what Drumalbin’s 100mph was.

Nowhere in Britain did sustained winds reach 74mph (other than possibly the tops of a few mountains). The flagship weather stations at Armagh and Eskdalemuir, which were both at the heart of the strongest winds, recorded 42mph and 39mph respectively, officially gale force on the Beaufort Scale.

It is, of course, all part of a deliberate media narrative to convince the public that our weather is getting worse, encouraged and directed by the Met Office. No wonder that the younger generation, who have no memory of the really devastating storms of the past, genuinely believe that storms such as Eowyn really are unprecedented and the consequence of climate change.

The Boxing Day Storm of 1998

THE LAST really severe storm to hit the UK was the Boxing Day Storm of 1998.

It hit both Northern Ireland and Scotland with 110mph winds, while many areas had winds of over 90mph, including Glasgow where 93mph winds blew down the steeple of St Stephen’s Church. The storm also shut down the Hunterston nuclear power plant.

Shortly after the storm, the Met Office told an inquiry into the resulting widespread power cuts that ‘the chance of a storm of similar severity occurring in Great Britain is probably of the order of one in four years’.

In short, severe storms were commonplace at that time. But there has been nothing since then that has remotely matched the Boxing Day Storm.

Paying for too much wind

Even if Ed Miliband manages to triple wind and solar power by 2030, as he plans, there will still be weeks when there is not enough wind power to supply demand. As I often say, double nothing is still nothing!

And the more wind capacity we build, the bigger the problem of surplus wind power becomes. Having too much power on the grid is as big a problem as too little. If supply exceeds demand, the system is overloaded, which can lead to blackouts when electrical equipment trips out.

At present NESO, who run the grid, can simply call on a generator to switch off in such an event. As both electricity demand and supply are pretty predictable, this is rarely an issue. But as the share of unreliable and unpredictable wind and solar power grows, the problem of surplus power becomes a serious one.

NESO will have no alternative but to pay wind and solar farms to switch off in these circumstances. They have estimated that this will cost over £3billion a year by 2030, all of which will end up on our energy bills. The boss of Octopus Energy reckons the bill could end up as high as £6billion.

We already pay £1billion for what are officially known as Constraint Payments, but these are invariably for Scottish wind farms because of the limited transmission capacity to England where the demand is. Octopus’s figure of £6billion will be on top of these existing payments.

NESO’s projections for 2030 state that a third of wind power generated will be surplus to requirements. Their £3billion cost estimate assumes that we can export most of this to Europe, albeit at a loss.

However when we have too much wind, it is likely that the rest of NW Europe will as well. There is unlikely therefore to be any demand for our electricity, unless we virtually give it away. If this happens, the bill could well exceed £6billion, with the electricity essentially being thrown away.

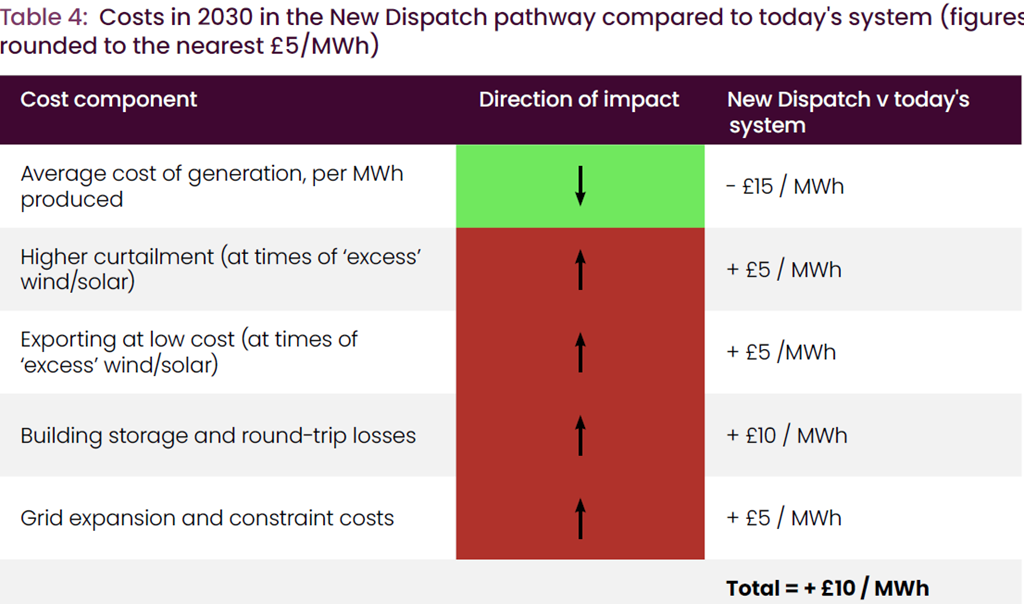

Miliband and NESO claim that these costs will be offset because, they say, renewables are cheaper than gas. However this is based on a lie. As the table below shows, they claim that generation costs will fall by £15/MWh. But this is based on the assumption of a massive increase in Carbon Tax on gas power, which would put up electricity prices. By replacing gas power with renewables, they can then claim that this has reduced prices, even though they will be no lower than they are now.

Based on NESO’s own costings, Miliband’s plan to build more wind and solar power could raise electricity prices by £30/MWh, which would mean a bill of £10billion a year, once all the costs of the transition are accounted for.

NESO Clean Power 2030