If you are unfamiliar with theological classics and want an easeful entryway, here is what you should do: run to On the Incarnation, a short treatise written by St. Athanasius of Alexandria in the fourth century, in the English translation done by Sister Penelope Lawson in 1944. It features an introduction by C S. Lewis, no less, who praises both the work and the translator for bringing it to life for modern audiences. It is the Church-Fatherly style as represented in this work that I want to dwell on here for a brief moment.

If you are unfamiliar with theological classics and want an easeful entryway, here is what you should do: run to On the Incarnation, a short treatise written by St. Athanasius of Alexandria in the fourth century, in the English translation done by Sister Penelope Lawson in 1944. It features an introduction by C S. Lewis, no less, who praises both the work and the translator for bringing it to life for modern audiences. It is the Church-Fatherly style as represented in this work that I want to dwell on here for a brief moment.

Athanasius’s little book would not be inaptly described as a breeze, a rarity for a work of theology to put it charitably. I read it in about two hours, spaced over a couple of days. Athanasius’ subject is the central Christian idea that fallen humanity needed a redeemer, and he argues why the Incarnation accomplished this in the only possible way. Refuting the arch-heretic Arius, the Egyptian cleric highlights the close connection between the Incarnation and the Atonement on the cross, showing why the latter completed the former. His theology emphasizes Creation and its goodness, and how Christ’s redemption restores the divine image in man. And he does all this in a way that is, as it comes across in Sister Penelope’s translation from the Greek, bracing and vivid and concise.

Lewis, a classical scholar himself, praises the work’s “classical simplicity.” The Athanasius–Lawson–Lewis triad forms a powerful nexus, suggesting an enduring style of Christian persuasion down through the ages. Lewis says as much in his introduction, pointing to the existence of a long line of “Christian classics” from the Bible and the Church Fathers on down to Francis de Sales, Pascal, Dr. Johnson, and many more, which all point to a substantial body of agreed truth despite differences in the finer points of belief and theology.

Enough of my comments—here is an excerpt from Athanasius himself, from his second chapter:

We saw in the last chapter that, because death and corruption were gaining ever firmer hold on them, the human race was in process of destruction. Man, who was created in God’s image and in his possession of reason reflected the very Word Himself, was disappearing, and the work of God was being undone. The law of death, which followed from the Transgression, prevailed upon us, and from it there was no escape. The thing that was happening was in truth both monstrous and unfitting. It would, of course, have been unthinkable that God should go back upon His word and that man, having transgressed, should not die; but it was equally monstrous that beings which once had shared the nature of the Word should perish and turn back again into non-existence through corruption. It was unworthy of the goodness of God that creatures made by Him should be brought to nothing through the deceit wrought upon man by the devil; and it was supremely unfitting that the work of God in mankind should disappear, either through their own negligence or through the deceit of evil spirits. As, then, the creatures whom He had created reasonable, like the Word, were in fact perishing, and such noble works were on the road to ruin, what then was God, being Good, to do?

It grabs you like a detective mystery, does it not? The whole treatise pulls you along with that kind of energy. Through his own style compounded of sound logic and true rhetoric, Athanasius sheds light on the Divine Style, on why God acts as he does. (You didn’t think God had a style, or had a right to a style? Our styles are mere epigonic imitations of his. Study the lilies, or the leaves, or a work of theology.)

I am emphasizing the question of style here for a good reason, namely that I feel it has gone out the window. Too often it seems that the way we express or carry ourselves doesn’t matter so long as we assume the right ideological posture. I am here to say (and I fancy that St. Athanasius will back me up, if he is listening) that manner matters just as much as matter, and medium is to a large degree one with message. Truth must be properly clothed—incarnated, you might say. Bare bones without out flesh, without the juice of real life, cannot satisfy the soul. Ideological posturing devoid of style is often accompanied by a know-nothing relationship to the great tradition, a lack of engagement with “the best that has been thought and said.” We live in narrow little rooms, and we would all become broader if we read the great books.

The Church Fathers lived at a time before the Gospel was unanimously accepted by all of society. They were members of an outsider camp, and they had to work hard to defend the beliefs of that camp and persuade the majority culture. (Our adversaries, of course, are no longer pagans but post-Christians, a different but related thing.) They did this through the exercise of a particular style, which was more often than not urgent, direct, simple, and emphasizing the fundamentals of the faith: creation, sin, redemption. Their essential closeness—both in time and in the temper and categories of their thought—to the apostles and Christ himself makes their writing invaluable to us. There is a purity in their diction that remains compelling today and reminds us why the Fathers have always been, through the Church’s history, a reference point and a compass, a source of clarity and unity.

Maybe part of the appeal of their writings is that they deal mostly with the basics and are not yet weighted down with a lot of ancillary questions, about who is saved and justified and how. For this reason, the Fathers have served as an antidote to modern controversies and the narrow concerns of an overdeveloped culture; speaking from the very dawn of Christian culture as it was born out of the ancient world, they are perennially fresh and relevant. Perhaps it’s a romantic sentiment, but the patristic period has always had in my mind the misty freshness and promise of an early spring dawn.

C.S. Lewis wisely says that we should “keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books.” The Church Fathers rank high on this list for the reader who is a believer, and Athanasius seems a fine place to start. He and his fellow Fathers are vital and necessary, and in a time of confusion (as no doubt the first centuries A.D. were as well) they can redirect our thoughts to the good, true, and eternally beautiful.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

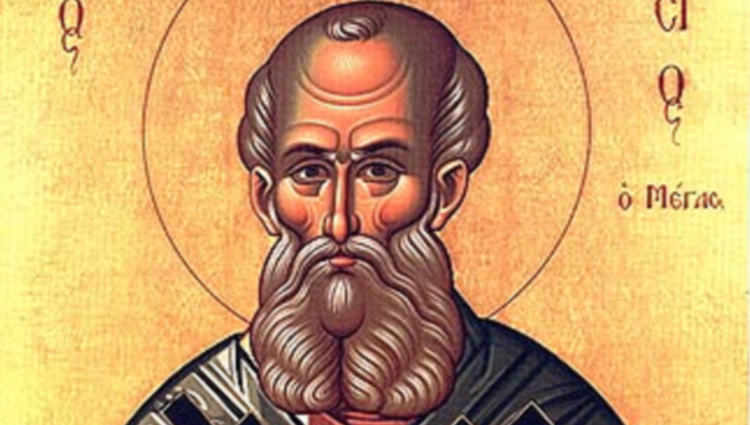

The featured image is an icon of Athanasius von Alexandria, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.