In Welsh, “Capel-y-Ffin” means “chapel at the boundaries.” It is an apt name, not only because of its location in the border land between Wales and England, but also because it is a place where the boundaries between religion and reality, monasticism and morality, chastity and carnality, and (it must be said) sanity and insanity were explored and violated.

My visit to England last summer took me to the Welsh Marches where I re-visited the ruins of Tintern Abbey in the Wye Valley, about which William Wordsworth— the grandaddy of romantic poets— wrote, and about which I commented here. Beyond Tintern is the town of Hay-on-Wye, and nearby lies the hamlet of Bredwardine—the parish of country vicar and diarist Francis Kilvert. More recently I regaled our readers with the story of Father Ignatius—the eccentric Anglican deacon who dreamed of restoring monastic life at Llanthony Priory and instead established a community in the same neck of the woods at Capel-y-Ffin in the Black Mountains.

My visit to England last summer took me to the Welsh Marches where I re-visited the ruins of Tintern Abbey in the Wye Valley, about which William Wordsworth— the grandaddy of romantic poets— wrote, and about which I commented here. Beyond Tintern is the town of Hay-on-Wye, and nearby lies the hamlet of Bredwardine—the parish of country vicar and diarist Francis Kilvert. More recently I regaled our readers with the story of Father Ignatius—the eccentric Anglican deacon who dreamed of restoring monastic life at Llanthony Priory and instead established a community in the same neck of the woods at Capel-y-Ffin in the Black Mountains.

Francis Kilvert and Father Ignatius were contemporaries, and in his diary Kilvert records how he hiked across the hills to visit Father Ignatius at his fledgling monastery.

I walked over to Capel y Ffin to see Father Ignatius and the Benedictine monks. Father Ignatius struck me as being a man of gentle simple kind manners, excitable, and entirely possessed by the one idea. His head and brow are very fine, the forehead beautifully rounded and highly imaginative. The face is a very saintly one and the eyes extremely beautiful, earnest and expressive, a dark soft brown. When excited they seem absolutely to flame. He wears the Greek or early British tonsure all round the temples, leaving the hair of the crown untouched. His manner gives you the impression of great earnestness and single-mindedness. Father Ignatius thinks every one is as good as himself and is perfectly unworldly, innocent and unsuspicious. He gave the contractor £500 at first, took no receipt from him. And so on. The consequence is that he has been imposed upon, cheated and robbed right and left.

Romantic at heart, Kilvert was intrigued by Fr Ignatius and his monastic endeavors, but comes away with sadly sensible conclusions:

I fear the monastery will never prosper. It is a noble and beautiful idea, but the time is not yet come for such a revival in the English Church. The soil is not prepared. The world is too strong. The monks are too few, too poor, too isolated. They have no endowment, no security, no sympathy from the clergy or the people round about. They live from hand to mouth. Father Ignatius is full of faith and fire, but he is building on sand. The storms will come, and great will be the fall of it. He trusts too much in men, and men will fail him. Already there are murmurs and desertions. One novice has gone back to the world, another is wavering. The contractor has cheated him, the neighbors laugh at him, the Bishop disapproves. Yet there is something very touching in the sight of these few pale young men in their black habits, working with their hands, praying at all hours, trying to live the life of the 6th century in the 19th. If only the Church were ready to receive them. But she is not. I came away sad at heart, with a heavy foreboding that this fair vision will fade and perish like the morning mist in the valley.

There must be something in the Welsh/English air in those valleys to inspire such unrealistic romanticism. Wordsworth felt it. Kilvert recorded it. Father Ignatius prayed it, and it is not surprising that another Englishman—driven by religion, romanticism and art was drawn to the same location.

Father Ignatius died in 1908, and in August 1924 the artist Eric Gill arrived at Capel-y-Ffin to establish an artistic monastic community on the site of Father Ignatius’ abandoned monastery. Gill arrived with his wife Mary, their growing family, and a handful of disciples— including poet-painter David Jones, printer René Hague, and assistant Lawrence Cribb.

Gill was born on February 22, 1882, in Brighton, Sussex, to a middle-class family of strict Protestants. His father was a Baptist minister, and other relatives were missionaries. He was apprenticed as a mason and stone carver at age 16 and trained first in making stone memorial inscriptions. By 1904 he had married Mary Ethel Moore, a former governess, and in 1914 they converted to Roman Catholicism.

After working in London, in 1907 Gill relocated to Ditchling, Sussex, where he founded a community of artists, craftsmen, and Dominican tertiaries. They aimed to lead a life of prayer and manual work inspired by the anti-industrialist and anti-capitalist ethos of William Morris. Distributism was a Catholic alternative, and Gill was friendly with Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton, and other prominent Catholic artists and writers of the age.

When Gill and his artistic ménage arrived at Capel-y-Ffin the site was a crumbling shell: leaky roofs, no electricity, and a valley so remote that supplies arrived by pony.

The rural retreat was beautiful but the weather harsh. The cold wind, rain, poverty, and hard work seemed perfectly suited to Gill’s vision of austerity and art. However, like Father Ignatius, he was away a lot. His work in sculpture and typography flowered, but he had to travel to follow up friendships, contacts, and commissions. David Jones’ painting and poetry also flourished. Their collaboration is chronicled in a recent book, Try the Wilderness First, by Jonathan Miles.

Gill was not only chasing commissions. He was also chasing skirts. His reputation has suffered enormously after Fiona McCarthy’s 1989 biography, which drew from Gill’s previously unpublished diaries. In them he recorded what Miles understatedly calls his “exuberant sexuality”. Despite his attempts at Dominican spirituality and determined Catholic commitment, Gill conducted numerous extra-marital affairs, made and collected nude drawings of friends, family, and visitors, and not only enjoyed nudity and promiscuity, but was incestuous with his sister and daughters.

Gill’s sojourn at Capel-y-Ffin, like Father Ignatius’, was short-lived. After four years he decamped to Pigotts in Buckinghamshire, where he set up another artist’s colony, completed his most famous commission—the Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral— and continued his “exuberant” mixture of religion, art, and indulgence.

In Welsh, “Capel-y-Ffin” means “chapel at the boundaries”. The lives of Father Ignatius and Eric Gill make it an apt name, not only because of its location in the border land between Wales and England, but also because it is a place where the boundaries between religion and reality, monasticism and morality, chastity and carnality, and (it must be said) sanity and insanity were explored and violated.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

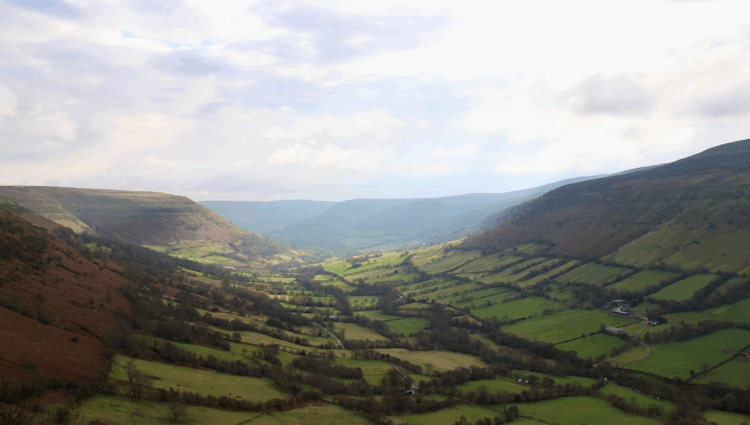

The featured image, uploaded by JamesWoolley, is a photograph of Capel-y-ffin, taken on 23 November 2010. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.