THE media called it the Storm of the Century. Hurricane Melissa, which devastated Jamaica last week, was certainly catastrophic: the death toll at the time of writing stands at 29. And, based on atmospheric pressure, it was the most intense Atlantic hurricane since Wilma in 2005. But Storm of the Century it most certainly was not.

Sadly, Jamaica has a long history of such hurricanes. One killed an estimated 400 people in 1722. Hurricane Charlie in 1951 cost 152 lives. The Greater Antilles hurricane of 1909 killed an estimated 4,000 across the Caribbean, notably in Haiti, and dumped an incredible 135 inches of rain on Jamaica. The biggest storm of the lot came in 1780. In what was known as the Great Hurricane, an estimated 27,500 lost their lives across the Caribbean. And so the list goes on.

Every time there is a big hurricane, the media are quick to use it as climate porn, putting the blame on global warming. As usual, the BBC was quick off the mark with this outright lie from its weathergirl, Sarah Keith-Lucas: ‘The frequency of very intense hurricanes such as Melissa is increasing.’

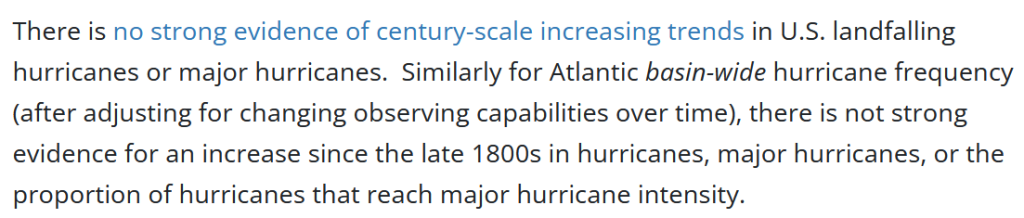

Not according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the acknowledged leading authority on Atlantic hurricanes. In their latest review on hurricanes published earlier this year, they stated:

https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/global-warming-and-hurricanes

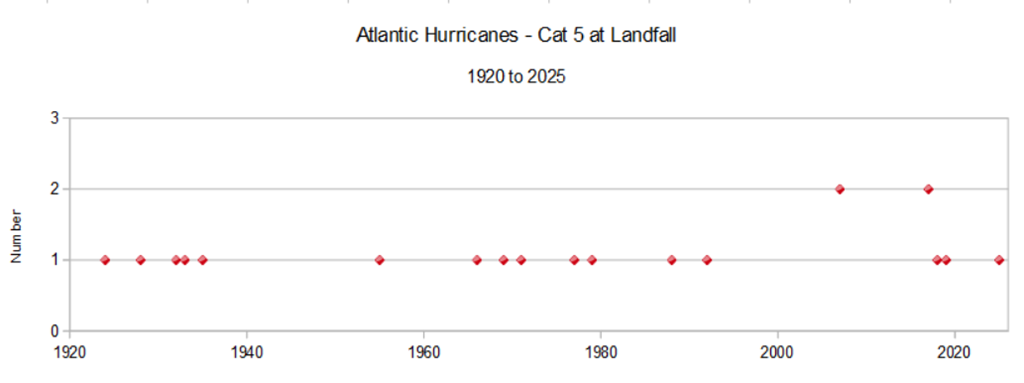

Major hurricanes are those rated Cat 3 and over. Below is a plot of hurricanes that have made landfall as Cat 5s, the highest category, including Melissa:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Category_5_Atlantic_hurricanes

There have been seven since Andrew hit Florida in 1992 out of a total of 20 since 1924. They are clearly not becoming more frequent.

The question of observation capabilities is crucial in the understanding of hurricane trends. Nowadays we have 24/7 satellite coverage providing data on wind speeds. In addition, there are hurricane hunter aircraft, robust enough to fly for hours inside the strongest of storms. With a full array of monitoring equipment on board, they are able to pinpoint peak wind speeds in a hurricane, even hundreds of miles from their base. Fifty years or so ago, this would not have been possible. Little was known about hurricanes out at sea, as ships would inevitably steer well away. As a result, many hurricanes out at sea which are recorded now would either have been missed in the past or recorded at much lower wind speeds.

One study by leading US hurricane experts in 2012 examined the ten most recent Cat 5 hurricanes and concluded that only two would have been classed as Cat 5 using technology available in the 1940s.

Estimation of wind speeds in the past largely relied on extrapolation from atmospheric pressure, which in turn needed a working barometer at the exact centre of the hurricane. The lower the pressure, the higher the wind speeds. Invariably, anemometers were blown to pieces in hurricane-force winds. Wind speeds historically tended to be understated at landfall as it was rare to get a pressure reading at the centre of the storm, which is normally only a few miles wide.

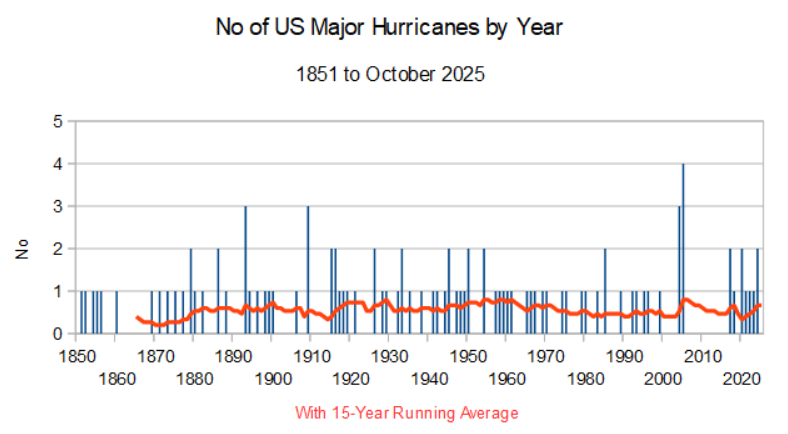

All in all, you simply cannot compare hurricane activity nowadays with that of the past. However, NOAA have very good data going back to 1851for hurricanes which have hit the US mainland. This data, as they have stated, confirms ‘no strong evidence of century-scale increasing trends’.

And here is their evidence:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-24268-5

Another trick deployed by the BBC and others is to compare mid-ocean wind speeds with landfall ones. For instance, it has been claimed that Melissa’s wind speeds of 185mph were as strong as the Labor Day storm which hit Florida in 1935 and is acknowledged to be by far the most powerful hurricane to hit the US. But Melissa’s wind speeds were not measured at landfall – instead they were estimated by hurricane hunters miles out at sea several hours before landfall.

This is an important point. Hurricanes almost invariably weaken as they approach land, partly due to shallower water and partly because the contours of the land disrupt the hurricane’s airflow. We, of course, see the latter effect with storms here in Britain. To compare winds at sea with those on land is therefore misleading. Yet this sort of misuse of statistics is now the norm where reporting of hurricanes is concerned.

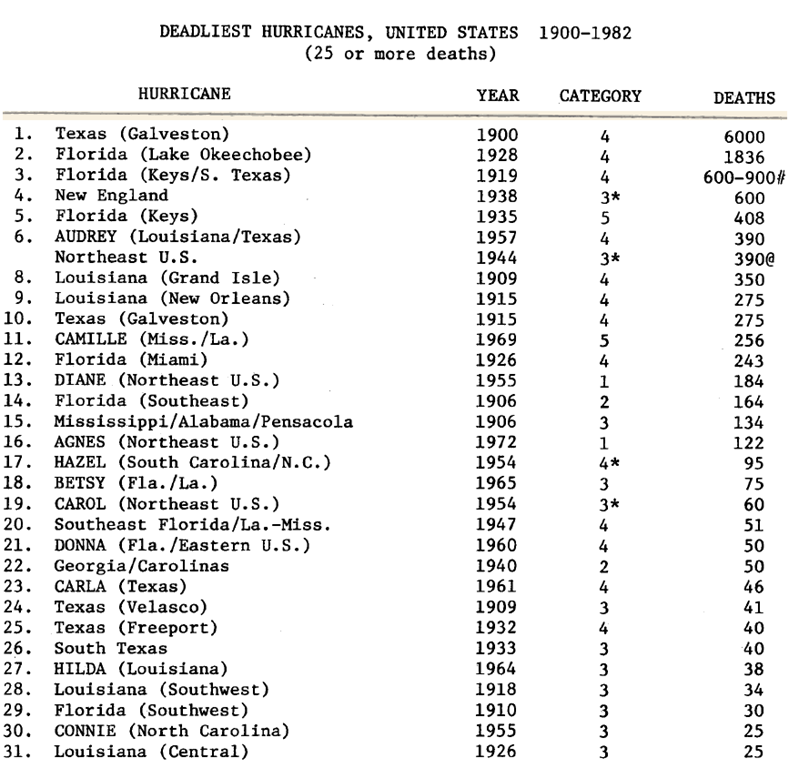

The simple reality is that catastrophic hurricanes have always brought death and destruction to the US and Caribbean. In 1983, long before hurricanes were looked at through the lens of global warming, NOAA published a review of US hurricanes which included this table:

Was Melissa any worse than the 1900 Galveston hurricane? Or Okechobee? Or the Great Miami hurricane of 1926, which wiped the city off the map and set back Florida’s newly burgeoning economy for a decade?

Or the Labor Day storm in 1935, still by far the most powerful hurricane ever to have hit the US? Or Camille in 1969, the second strongest? The answer is clear.