Can acts of seemingly pure self-sacrificial love be morally reckless? F. Marion Crawford’s dexterous handling of such questions in “The Heart of Rome” marks the novel as deserving a place in the canon of great twentieth-century literature.

Having just finished writing a fifty-part series for Crisis Magazine on “Unsung Heroes of Christendom”, I’ve been spending much time over the past two years with those who have been unjustly forgotten or neglected. These include authors who are not as well-known or as celebrated as they should be, such as Maurice Baring and Malachy G. Carroll, the former of whom wrote several bestselling novels between the two world wars and the latter of whom wrote several novels in the years following World War Two.

Having just finished writing a fifty-part series for Crisis Magazine on “Unsung Heroes of Christendom”, I’ve been spending much time over the past two years with those who have been unjustly forgotten or neglected. These include authors who are not as well-known or as celebrated as they should be, such as Maurice Baring and Malachy G. Carroll, the former of whom wrote several bestselling novels between the two world wars and the latter of whom wrote several novels in the years following World War Two.

Carroll’s best-known and most successful novel, The Stranger, which enjoyed considerable success when it was published in 1952, has been resurrected recently in a new edition by Cluny Media enabling a new generation of readers to enjoy the saga of an unjustly maligned priest who seeks refuge in a small town in Ireland. In my essay for Crisis Magazine, I praised John Emmet Clarke and Scott W. Thompson of Cluny Media for publishing the new edition of The Stranger, rescuing it from oblivion. Similar praise is due to John Riess, the founder of Angelico Press, for having the vision to bring back into print The Mass of Brother Michel, an historical novel by Michael Kent, set in sixteenth century France, which is one of the finest works of twentieth century Catholic fiction, the neglect of which since its publication in 1942 has been scandalous.

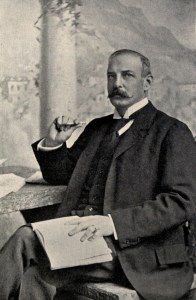

My recent enjoyment of these resurrected novels induced me to finally take from the shelf The Heart of Rome by F. Marion Crawford, another resurrected novel which has reproached me from its dust-gathering place on the shelf whenever my eyes have fallen upon it in the third of a century since I first purchased it in 1992. Although it is unlikely that most twenty-first century readers will have heard of Francis Marion Crawford, he enjoyed considerable success as a novelist in the late Victorian and Edwardian period. Born in Bagni di Lucca, a small town in Tuscany, in 1854, he lived a life of cultured cosmopolitan opulence. His father was the American sculptor, Thomas Crawford, who is celebrated for his contributions to the splendour of the United States Capitol, including the Statue of Freedom atop its dome, as well as the Washington Monument in Richmond, Virginia, and the statue, David Triumphant, in the National Museum of Art. His mother was a daughter of the affluent banker and benefactor, Samuel Ward. He would be educated successively at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire; at Cambridge University; and at the Universities of Heidelberg and Rome. After periods living in India and the United States, he settled permanently in Italy. In 1880, he was received into the Catholic Church. Four years later, he married Elizabeth Birdan, the daughter of the American Civil War general, Hiram Birdan. They had two sons and two daughters.

The first of F. Marion Crawford’s many novels was published in 1882 and he would continue to write until his death at his home in Sorrento on Good Friday in 1909. The Heart of Rome, the novel that has haunted me reproachfully from its exile on the shelf, was first published in 1903. The edition that I own had been newly published when I bought it in 1992 by Fisher Press, a small and adventurous Catholic publishing house founded in England by Anthony and Mary Tyler, a husband and wife team, both of whom were converts to the Catholic faith. As with the pioneering founders of the aforementioned Cluny Media and Angelico Press, the Tylers were motivated by the desire to bring neglected classics back into print. Among the Fisher Press titles that I purchased during the final decade of the last century, and the final decade of my own life in England, were William Cobbett’s wonderfully rhetorical History of the Protestant Reformation, Bernard Holland’s Memoir of Kenelm Digby, one of the true giants of the Catholic Revival in the nineteenth century, and Hugh Dormer’s War Diary, an edifying account of the author’s clandestine missions in Nazi-occupied France as a sort of latter-day Scarlet Pimpernel. These have either been read or at least browsed through, their pages being cracked open, whereas The Heart of Rome remained untouched in its pristine state. That was until a few weeks ago when my experience of reading The Stranger and The Mass of Brother Michel prompted me to pluck it from the shelf and plunge into its pages.

What a joy awaited me, albeit that I found somewhat tedious the sections recounting the excavations being carried out under the palazzo in Rome in which the novel is mainly set. For those with an engineering frame of mind, the lengthy descriptions of these painstaking excavations in the labyrinthine cellars will no doubt be riveting; for the rest of us, the discovery of the priceless treasure and the perilous presence of the mysterious “lost waters” are much more engaging. Most important, however, is the romance that develops between the disinherited and impoverished aristocrat, Donna Sabina Conti, and the intrepid and adventurous archeologist and architect, Marino Malipieri. It is the way that Crawford handles this relationship, in which eros dances decorously with chastity, without the one ever stepping ineptly on the other, which is the true mark of a great work of romantic fiction. Few authors can get this right. Jane Austen does so impeccably, as does Manzoni with the relationship of Renzo and Lucia in The Betrothed, but they are very much the exception to the rule. Crawford even takes risks that Miss Austen and Manzoni would not have taken. Whereas they are careful to chaperone their heroes and heroines, preventing inappropriate intimacy, Crawford permits his two mutually attracted protagonists to embrace intimately without the loss of the chaste restraint that tames the fires of erotic desire. He does so with an innovative ingenuity which the reader needs to discover for himself.

Apart from the masterful control of eros, The Heart of Rome addresses other moral dilemmas with an all too rare balance and perspicacity. To what extent does Malipieri’s sense of honour and duty undermine the need for prudence and temperance? Can acts of seemingly pure self-sacrificial love be morally reckless? Is such recklessness reprehensible? Great literature asks such questions with literary dexterity, subsuming the moral struggle within the narrative without succumbing to preachiness or didacticism. F. Marion Crawford’s handling of such questions in The Heart of Rome marks the novel as deserving a place in the canon of great twentieth-century literature.

Following Crawford’s death, the great American novelist Henry James wrote to the English novelist, Hugh Walpole, that Crawford was “romantic in all his gestures, so handsome and vigorous, driving his boats fearlessly into the most dangerous seas; building his palaces on the Mediterranean shore, travelling over every corner of the globe, fearless and challenging and heroic”. There is nothing one could possibly add to James’ description of Crawford. I am, however, willing to assert that The Heart of Rome is as “fearless, challenging and heroic” as its author. It is a rediscovered gem, hidden by the sands of neglectful time, which, plucked from the dust, deserves its place in the literary diadem.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a photograph of F. Marion Crawford, published by L C Page and company, Boston, in 1903, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.