FOUR hundred yards is a distance that normally does not demand attention. It is the length of an unhurried walk, the space between a hesitation and decision. In London, it separates Montpelier Square from Great Cumberland Place – a residential address from a public monument.

On the night of March 1, 1983, Arthur Koestler and his wife Cynthia took their lives in their flat at 8 Montpelier Square. Koestler, then 77, was a former Communist who had written extensively on totalitarianism and became one of the most prominent voices of intellectual disillusionment in the 20th century. He had announced the decision to commit suicide, justified it in writing, and carried it out with the deliberate calm of a man who had spent his life arguing with himself and finally decided to end the debate.

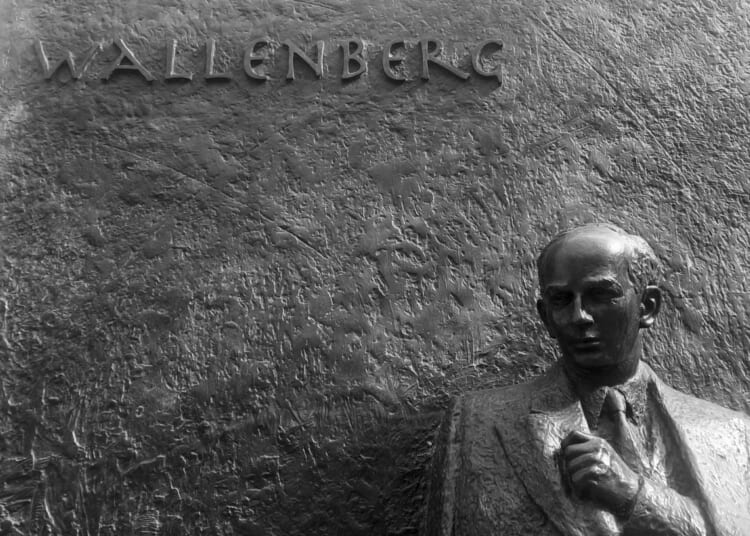

Less than a quarter of a mile away stands a statue of Raoul Wallenberg, unveiled in 1997 by Queen Elizabeth. Wallenberg had been missing for more than half a century by then. There was no suicide note, no certainty of death, no body. Only absence, prolonged to the point where it became a political fact.

The distance between Koestler’s last residence and Wallenberg’s memorial is moral, almost metaphysical. One man chose his ending; the other was denied one. One devoted his life to explaining history; the other changed its course.

Koestler was born in Budapest in 1905, at the heart of Central Europe; Wallenberg in Stockholm in 1912, at its northern edge. Koestler was born into a Jewish family that trusted education and reason as shields against barbarism. Wallenberg belonged to a powerful banking dynasty, protected by wealth, diplomacy and Sweden’s neutrality. Yet Budapest was their common denominator – a city that would shape Koestler’s mind and test Wallenberg’s character.

Koestler was the product of a generation that believed history could be steered by reading a manual of instructions. The catastrophes of the interwar years assured him that liberalism was exhausted and fascism ascendant. Communism, for all its brutality, at least claimed to possess a solid theory – a guide with detailed, step-by-step directions on how to operate, assemble, maintain and troubleshoot a society. For an intellect like Koestler’s, that claim proved irresistible. He joined the Communist Party in 1931, not out of innocence but out of desperation.

His disillusionment, when it came, was devastating. His novel Darkness at Noon remains one of the most incisive anatomies of totalitarian logic ever written precisely because the author was a former believer. Koestler understood how systems convert doubt into guilt and murder into necessity. But that understanding came at a cost. Once the illusion collapsed, nothing else quite replaced it. The rest of his life was spent fighting ideologies without quite believing in alternatives.

Wallenberg never shared that temptation. He arrived in Budapest in 1944 not as a theorist but as an improviser convinced that knowledge is based on experience and evidence. Working under the auspices of the Swedish legation, he distributed protective passes, rented buildings and declared them Swedish territory, bluffed SS officers and bribed Hungarian officials. His tools were audacity, paperwork and nerve. He did not seek to interpret or defeat Nazism; he sought to obstruct it. There was no doctrine behind his actions, no universal claim, only the practical conviction that lives could still be saved if someone acted quickly and shamelessly enough.

Having helped rescue tens of thousands of Jews, Wallenberg disappeared. Arrested by the Soviet Red Army on January 17, 1945, he entered a different totalitarian system – one that Koestler knew intimately. The irony is inescapable: the man who fought Nazism with administrative cunning vanished into the very machinery Koestler spent most of his life exposing.

Koestler chose his death. Ill – he had Parkinson’s disease and leukaemia – fearful of dependency and persuaded that his life’s narrative had reached its end, he treated suicide as a final assertion of autonomy. It was an act consistent with a man who believed that reason, even when defeated, should remain in control.

Wallenberg’s ending was stolen. Whether he died in 1947, 1957 or decades later is still a mystery. What matters is that his fate dissolved into the grey anonymity of the Soviet incarceration system – the Gulag. No explanation, no closure – only silence. As the distinguished scholar Yoav Tenembaum put it, Wallenberg is a hero without a grave.