IT IS the Christian season of Epiphany, and God knows we are due an epiphany in the world of autism.

We desperately need an overhaul in mainstream thinking such that we ask the obvious questions: Why do we have a growing autism problem? What can be done to support those affected? How to save the next generation from the same fate?

Instead, we see the numbers go up, year after year, only to be told these cases don’t count. With straight faces, experts will repeat the mantras that it is just ‘better awareness’, ‘wider diagnostic categorisation’ and a desire for ‘greater inclusion’. Packaged with the bow of ‘neurodiversity’, the experts are confusing us all.

Sadly, however, the neurodiverse chickens are now coming home to roost in the barns of Whitehall. The government needs to make cuts and if the problems aren’t real, the funding can go.

There has been a recent drip-feed of press articles outlining the likely changes that are coming for children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND). We are told that too many children are given support and there is scope for greater inclusion (read cuts).

It is obvious that Ministers, their advisers and experts have no experience of childhood autism. If they did, they would address it as a national emergency. They would also insist on integrating attention to children’s health alongside efforts to meet their educational needs. Without support for their health, there is little chance they can learn.

The rest of this article revisits a survey of parent experiences that was conducted with the charity Thinking Autism just over a decade ago.

We asked parents and carers questions about the problems affecting their children and their experiences of trying to access support for their health.

Our survey was answered by 264 parents and carers of children with autism – an amazing number considering how stretched and stressed we all are.

In terms of the challenges faced, the majority reported a very long list of concerns.

Almost all had significant problems with behaviour such as irritability, agitation, anxiety, lethargy and/or hyperactivity and obsessive speech.

More than half had a significant problem with aggression.

Almost all reported a significant challenge in relation to sensory processing (sound and environment).

The majority reported significant problems with eating, diarrhoea or constipation as well as other gastrointestinal problems, incontinence, acid reflux, mouthing behaviours (chewing clothes/teeth-grinding).

Most had challenges with sleep.

The majority had significant problems with fine or gross motor skills.

As many as a third faced the problem of seizures or epilepsy.

In the open comments box, respondents told us about:

‘Hand biting, arm flapping, hitting things and people, posturing after meals, defiance, aggression, oppositional behaviour.’

‘Smacking one hand on top of the other and biting his hand or fingers to the point where his skin is now leathery as it hasn’t had a chance to heal.’

‘Reflux and diarrhoea from 2-3 weeks old with frequent night waking. A weighted blanket has made a big difference but will still wake 1-7 times at times when feeling anxious.’

‘Will not chew or swallow solid foods at the age of almost 5 years, [food] has to be liquidised but will chew anything wooden, metal or plastic.’

‘Complete loss of speech at age 2 1/4 coincided with onset of diarrhoea. Sleep problems can mean waking at 3am and not getting back to sleep again.’

These children were obviously extremely unwell and very distressed.

As you’d expect, almost all the parents and carers had approached the NHS for support but very few were satisfied with the treatment received. Children were left, often for years, in major distress:

‘We had horrendous diarrhoea for years, [and are] constantly told it is “toddler diarrhoea” which is nonsense as he is no longer a toddler . . . he has severe eating disorder [being] unable to swallow solid foods without choking or vomiting but no help is given. The attitude is very much “get on with it”.’

‘The NHS seem bewildered – especially the GPs. They assume his gut issues are “in his mind” and “part of his autism”.’

We discovered that it was only epilepsy that was taken seriously, and even then, the treatment available often failed to resolve the problems involved:

‘My son has had multiple physical problems: chronic constipation, self-harming, food intolerances, epilepsy. Yet it is only the epilepsy which has been taken seriously (although the treatment has been ineffective to date). All his other issues have been dismissed as “just autism” and there has been a reluctance to offer any kind of investigation or treatment.’

In the main, the diagnosis of autism overshadowed any desire to treat the problems encountered. Once labelled autistic, children were left to suffer, and their parents and carers had to find alternative help.

As one parent explained: ‘When my daughter was small, whatever symptom my daughter was troubled by, her paediatrician would say that it was autism. My husband and I felt like if my daughter was having a heart attack the paediatrician would say “that’s autism”. We gave up seeing her and tried to help our daughter ourselves.’

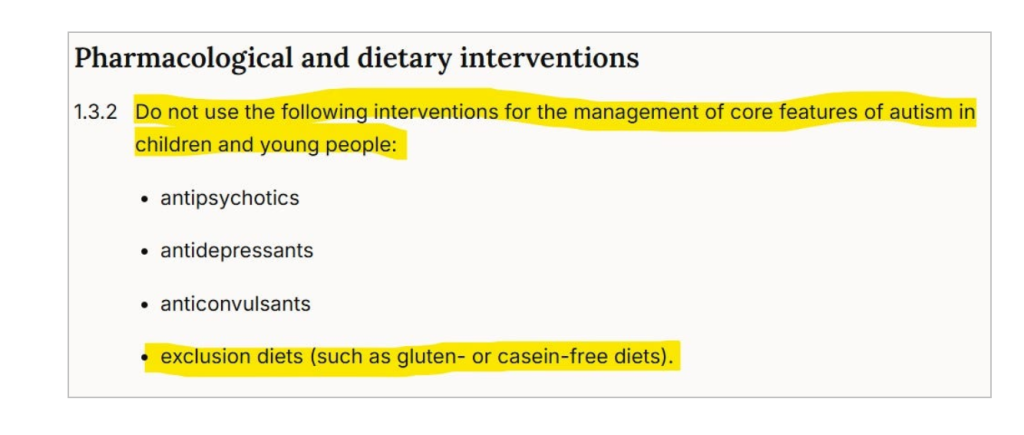

Almost all respondents had tried different ways to help improve the health of their children. Relatively simple diets were the most effective, with almost all reporting ‘significant’ or even ‘life changing’ improvement as a result. To this day, however, the panel of experts constituted by the National Institute for Care and Health Excellence (NICE) to write the guidelines advising NHS staff about support and management for children with autism (CG170) advise against the diets that work:

This feels like more than simple neglect or diagnostic overshadowing and more like deliberate discrimination. There is a willingness to leave our children in pain.

Moreover, when you read parental reports of what dietary changes can do, it is truly shocking that parents are not routinely supported to have a go. Here are two examples with many others included in the published version of our report:

‘After taking our son off dairy products, at age three and a half, nearly three days exactly to the hour he started naming letters and numbers! We didn’t even know if he knew them or not although we suspected he did. We didn’t believe in the diet but thought it was worth “giving it a go”. Diet and supplements have played a huge part in his life ever since.’

‘As soon as I removed gluten and casein from my son’s diet he changed significantly – almost overnight. He went from oppositional, irritable, extremely hyperactive and spacey to much more compliant. School noticed the change instantly. Before removing casein and gluten I was frightened he would run into the road. I used to grab him by the hand to keep him next to me but he used to pull away saying it hurt. He would never ever hold my hand. He said it hurt but I thought he was being difficult! He would either be running ahead of me or lagging way behind complaining he was exhausted and demanding to be carried to school. I kept him in a buggy way past his peers because I was afraid of where he would end up if I let him out. A couple of weeks after removing gluten and casein he was walking to school next to me and then he quietly slipped his hand into mine and held my hand. What more can I say!’

Our research found that parents were sick and tired of seeing their children suffer and the NHS do nothing or worse in response. They felt that the experts – even those in autism teams – were woefully ill-advised and ignorant about the nature of the condition. Parents were routinely ignored and if anyone listened, it was by chance not design.

Sadly, I fear nothing has improved in the decade since we did the research.

Indeed, as we know, the number of children affected has gone up. The pressure on services has increased. There has been no change in the dominant narrative about the condition and misconceptions about ‘neurodiversity’ have been further entrenched.

Fiddling on the edges of funding for schools will do nothing but make it all worse.

As we remember the ‘wise men’ (Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar), who followed the star and witnessed the arrival of light in the darkness, it is timely to pray for an epiphany about autism.

Our children bring light to the darkness and could help to save the next generation from the same fate.

During Epiphany, people recall the names of the Magi and repeat the words ‘Christus mansionem benedicat’ (May Christ bless this house). It is a time to remember and bless the households struggling with autism. Those parents and children are hurting and they need to be heard.