To enter a universe peopled with objects whose function is to give pleasure is also to establish contact with the order of pure beauty.

To enter a universe peopled with objects whose function is to give pleasure is also to establish contact with the order of pure beauty.

The words “beauty” and “beautiful” have become unfashionable, not indeed with artists, who use them quite freely even in our own day, but rather with the school of those aestheticians who intend to handle the realities of art with the same scientific methods that befit the realities of nature. The beautiful then is rejected as a “metaphysical” notion unworthy of our attention. But nothing is simpler, more concretely evident, than beauty, and its experience is familiar to all. In reading books, we usually content ourselves with understanding the meaning of the sentences, pages, and chapters. If we stumble upon some passage whose meaning escapes us, either on account of the obscurity of the style or because of the intrinsic difficulty of the subject, we read it again, but not for pleasure. We never desist from reading the passage in question until, owing to our renewed efforts of attention, its meaning becomes clear to our mind. Then, at last, we know what our text means. But precisely because we then are in the order of knowledge and of truth, we stop reading the sentences that have so long detained our attention. If we read a book to learn the truth it contains, the aim and purpose of our reading is to rid ourselves of the need of reading the same book again in the future. This is the kind of book of which one says: “I do not need to read it because I know what there is in it.”

But there is an entirely different class of books. We have already read them, understood them, and some of them are so familiar to us that we could recite parts of them, as the saying goes, “by heart.” Still we want to read them at least once more. We shall always desire to repeat our past experience, not in the least because we hope to learn from such books something they have not yet taught us, but simply because of the pleasure we are sure to find in reading them. This well-known experience usually attends our first contact with certain sequences of words and sounds that leave in us a sweet wound more desirable than many material satisfactions. At first, this is not a question of understanding; usually, the understandable element of the sentence is very simple, so much so that, as often as not, there is nothing to understand at all… Any time we feel an irresistible urge to stop, to linger upon such an experience, to repeat it for the mere pleasure of experiencing again, we can feel sure that beauty is there.

When joy is experienced by sense and in sense, its true name is pleasure. Words always betray such experiences. In the present case, it should be made clear from the outset that, because to see is to know, the pleasure of aesthetic experience is that of cognition. The desire to repeat it is the desire of repeating an act of cognition. Moreover, since the cause of pleasure lies in the very apprehension of a certain object, the desire to repeat it expresses itself in a series of intellectual efforts whose aim and purpose it is to deepen, to clarify, and, in a word, to perfect our knowledge of its cause. This is one of those cases in which a continuous exchange takes place among pleasure, love, and knowledge, the desire to know springing from the pleasure that the sight of a certain object can give and, in turn, the pleasure itself feeding on an always more intimate knowledge of its source. The pleasure that is here at stake is exactly of the same sort as that of contemplation. And, indeed, aesthetic experience is, first and foremost, a sensible contemplation that blossoms in an intellectual inquiry into its cause. Therefore, in saying that aesthetic experience is that of a pleasure, we shall always point out the kind of emotion a man experiences in contact with an object whose apprehension is desirable for its own sake. The beautiful is that which, in the object itself, is the cause of such emotions, or of such pleasures, of such acts of cognition.

Read in the light of these simple facts, many ancient doctrines recover the fullness of a truth that has been obscured by too many misunderstandings. The Scholastics used to define the beautiful (pulchrum): that which pleases when seen. A similar position was upheld in the seventeenth century by Nicolas Poussin, when he defined painting: “An imitation of anything visible that is under the sun, done on a surface by means of lines and colors. Its end is delectation.” To be sure, the word “delectation” conveys the notion of an emotion more complex than what is commonly called pleasure, but, precisely, whatever the mind contributes to the pleasure of the eyes is there in view of turning this pleasure into a protracted delectation. In the very last lines of his Journal, Delacroix has noted in pencil this ultimate reflection: “the first quality in a picture is to be a delight for the eyes.” It would be a pity to lose sight of a position that has obtained the support of Aristotle, Poussin, and Delacroix. But the best way to ensure its survival is perhaps to examine its ultimate implications.

As has been seen in its place, an object is said to be a work of art for the elementary reason that it owes its very existence to the art of an artist. But it owes to the same art to be such as it is, and if it has been of such nature that its sight gives pleasure to those who experience it, the cause that makes it an object pleasing to human eyes remains inherent in it, or consubstantial with it, as long as it remains in existence. This is to say that the beautiful hangs on our actual experience of it as far as its aesthetic mode of existence is concerned, but its physical existence is as independent of the fact that it is being experienced or not as the physical existence of the work of art itself is. And no wonder, since for a work of art to be and to be fully actualized as an actually existing work of art are one and the same thing. Here, as in all similar cases, there is nothing to prevent a philosopher from adopting an idealistic attitude. We can pretend to believe that the intrinsic physical characteristics that make some Egyptian paintings such an unexpected joy to the eye simply ceased to exist during the millenniums they spent in complete darkness, invisible to human eyes. The least that can be said about such a supposition is that it is a wholly gratuitous one. Successfully achieved works of art are not beautiful because they please our eyes; they please our eyes because they are beautiful. Their beauty is coextensive with their duration as it is consubstantial with their being as works of art.

On the other hand, it is true that the beautiful reveals itself and reaches one of its ends in the human act of cognition by which it is being actually apprehended. In this respect even the classical formulas in which the Scholastics used to speak of the beautiful are apt to be misleading. In saying that the beautiful is that which pleases when seen (id quod visum placet), one seems to say that the beautiful consists in the pleasure that it gives to those who perceive it. But their complete view of the problem was more complex than one might surmise from this abbreviated formula. First of all, since the beautiful is apprehended by an act whose repetition is desirable, it is an object of love. But that which is an object of love is apprehended as a certain good. For this reason, the beautiful is a particular case of the good. It is the kind of good found in the very apprehension, by sense, of any kind of being so made that there is pleasure in the very act of apprehending it. This is not an exclusive property of works of art. Every sense perception whose act is enjoyable for its own sake is an intimation of the objective presence of beauty in its object. Things of nature, such as landscapes, seascapes, animals, human figures and faces, even the works of man’s industry, such as cities, utensils, and the most modest of man-made objects—in short, everything that in any sense of the verb can be said “to be” is susceptible, under favorable circumstances, of becoming an object of pleasurable experience. One then realizes that the thing is beautiful. The nature of this experience is the same with the works of nature as it is with the works of art. The beautiful is the same in both cases. Not, indeed, our own apprehension of it, but that, in reality, whose nature is such that there is for us pleasure in the very act by which it is being apprehended.

__________

This essay is taken from Painting and Reality.

Republished with gracious permission from Cluny Media.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

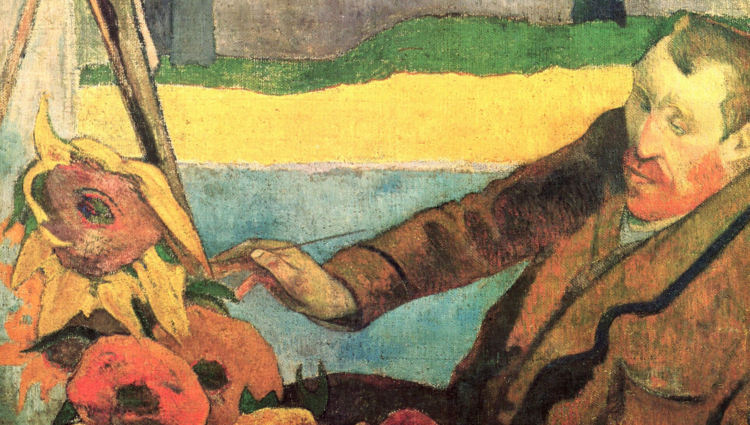

The featured image is “The Painter of Sunflowers” (1888), Paul Gauguin, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.