Historian Walter McDougall is that rare “twofer”: a wonderful writer of history and a wonderful lecturer. In this book, he combines essential tips for the writer with a series of uniformly sparkling essays that range from the era of the American Revolution to the present day.

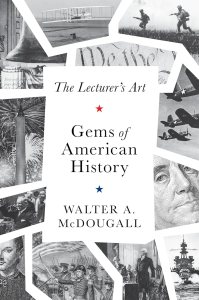

Gems of American History: The Lecturer’s Art, by Walter A. McDougall (309 pages, Encounter Books, 2025)

Walter McDougall must be one of those rare twofers among academic historians. A wonderful writer of history, because he never forgets that history is a story, he must also be a wonderful lecturer, given the care that he says he has always put into his lecture preparations. Never having experienced a McDougall lecture, I can only claim to have read many a McDougall book. But I can make this much of an additional claim. Looking back on my now semi-ancient graduate student years, I can recall a very few sparkling lecturers of note and more than a few productive scholars. But I can’t summon up a single twofer among them. So, hat’s off to Professor McDougall.

Walter McDougall must be one of those rare twofers among academic historians. A wonderful writer of history, because he never forgets that history is a story, he must also be a wonderful lecturer, given the care that he says he has always put into his lecture preparations. Never having experienced a McDougall lecture, I can only claim to have read many a McDougall book. But I can make this much of an additional claim. Looking back on my now semi-ancient graduate student years, I can recall a very few sparkling lecturers of note and more than a few productive scholars. But I can’t summon up a single twofer among them. So, hat’s off to Professor McDougall.

And hat’s off to this fetschrift of sorts. Oops, I just violated a McDougall writing “tip.” Rules aside, the McDougall preface to this collection of McDougall essays (hence a fetschrift—of sorts—by himself and to himself) is titled “Tips on Editing Your Own Work to Achieve a Crisp Writing Style.” Among those tips are his cautioning against opening a sentence (much less a paragraph!) with “and.” For that matter, he isn’t wild about beginning a sentence with “there” or ”it” either. Too often, they invite the dreaded passive voice.

And then there are certain words. (There I go again.) “Appropriate” is one of them. For McDougall the word is never, well, never appropriate “because it means nothing.” He continues: “Without accompanying standards of propriety the adjective ‘appropriate’ is a waste of four syllables.” No wonder, he cannot resist, that politicians often resort to it.

While he’s at it, adjectives and adverbs in general should always be kept to a minimum. His advice? Come up with a vivid verb or noun instead. The temptation to deploy a “very” or a “mostly” or a “somewhat” should not just be avoided; it should be rejected—or spurned—or junked—or jettisoned. An example? Write “torrid” rather than “very hot.” Of course, torrid could serve as a vivid adjective as well.

Eight-plus pages of McDougall “tips” concludes with those classic Orwell “rules” contained in his 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language.” No tips here. Orwell had rules. All of them are worth repeating, but one will suffice here: “If it’s possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.” That’s “always” rather than just “sometimes.” McDougall might have added at least this much: especially if the word that is being targeted for removal is an adjective or adverb.

The content of these uniformly sparkling essays range from the era of the American Revolution to the present day. (Why not both an adverb and an adjective when the noun is both inevitably and necessarily as bland and ordinary as “essay,” each one of which in this collection happens to be not just worth reading, but well worth reading.) This review will focus on five: “America’s Machiavellian Moment,” subtitled “Origins of the Atlantic Republican Tradition”; “The Grand Strategic Consequences of the Allegedly Foolish War of 1812; “The Madness of Saint Woodrow,” subtitled “Or, What If the United States Had Stayed out of the Great War”; “No Discharge from that War,” subtitled “The Vietnamization of America”; and “Can the United States Do Grand Strategy?”

Was the period between 1774 and the organization of the First Continental Congress and the 1789 ratification of the Constitution the Machiavellian moment for the birth of the United States that British historian J.G.A. Pocock contended that it was? Yes—and no—concludes McDougall. “Assuredly,” suggests McDougall, it was just that in that “earnest men deliberated on how to craft a republic that might endure like the Venetian one.”

And yet McDougall agrees with Hillsdale Professor Paul Rahe that the presumed link between Machiavelli and the American Founders ignores too much. John Adams is McDougall’s prime example. On the one hand, “no American devoted more thought to the Florentine’s writings than John Adams.” On the other hand, Adams “broke with him entirely on moral questions.” For Adams the machinery of government, the practical matter—and importance—of the separation of powers was not enough to ensure a successful republic. In other words, religious faith was not just important, but the “indispensable buttress for a healthy republic.” At least that was the case for Adams and many of his compatriots. Adjectives can sometimes be not just helpful, but exceedingly helpful, even downright vital. At least that seems to be McDougall’s ultimate contention on this very important point.

His “tips” notwithstanding, McDougall seems to more than occasionally violate one of them. After all, his essay on the War of 1812 deals not just with its consequences, but with its “grand strategic consequences.” And the war itself was not just the War of 1812, but the “allegedly foolish” War of 1812.

It’s easy to have some rueful fun with the War of 1812, the war that might not have happened had there been modern communications, and a war that might have ended without the Battle of New Orleans and the making of Andrew Jackson had there been modern communications. Then there was the war itself and the burning of Washington, DC, as well as the shelling of Fort McHenry and the birth of our national anthem set to the tune of an English drinking song.

But McDougall is not out to have any fun at all in this essay. Instead he is downright serious—and properly so. After re-telling the oft-confusing story of the road to war, which concluded with a divided House and Senate voting 79-49 and 19-13 respectively for war with England, McDougall offers this conclusion: “But the consequences for the United States of this allegedly unnecessary conflict cannot be overstated.”

For starters, the war “ushered in two decades of one-party government” led by Democratic-Republicans who “now understood the need for such Federalist institutions as a strong central bank, a standing army and navy, and government support for manufactures.” More than that, “every sector of the U. S. economy and every section of the nation boomed” in the aftermath of that war. Last, but far from least, Great Britain lost its “best chance (to) forestall the rise of the United States.”

Now let’s fast forward to a highly significant, perhaps the most highly significant, long term consequence of the post-War of 1812 rise of the United States, namely the 1917 decision of Woodrow Wilson to do the wishes of England and take this country into the Great War that had begun in 1914. That Professor McDougall has his issues with both that decision and the accompanying Wilsonian call to “make the world safe for democracy” might be more than slightly given away, having captured it as he did under the title of “The Madness of Saint Woodrow.”

As McDougall sees it, Wilson had four options in the spring of 1917: 1) remain neutral and accept the “risk of a German victory; 2) enter the war on the “realistic grounds” of preserving the European balance of power and American security; 3) fight a naval campaign “rather than shipping an army to France”; 4) enter the war on the basis of a “crusade, a holy ‘war to end all war,’ which would “enthrall Americans with that fantastic mission,” and thereby “hope to persuade or cajole Europeans to convert to it, too.”

We don’t need to guess which option Saint Woodrow selected. Nor do we need to guess what McDougall thinks of that option. He then proceeds to speculate that Wilson’s third choice “might have been the best,” because it would have a) been “far cheaper”; b) given both sides a “powerful new incentive to end the carnage”; c) left matters to the European powers to “hammer out a compromise peace.”

Saint Woodrow, of course, would have none of the above, having convinced himself that “God was calling America to redeem the horrible war by turning it into a “war for righteousness.” In the end he not only did not make the world safer for democracy, but McDougall contends that it could even be argued that his “hapless policies toward Russia” wound up making the world “safe for communism.”

Now let’s jump to one of the consequences of a post-Wilsonian world, a world that had been made safer for communism, namely the American war in Vietnam, a war in which a young Walter McDougall served. Recall the title of the piece: “No Discharge From That War.” Why does McDougall think that that has been the case? Because in the end “America itself underwent Vietnamization.”

Before McDougall explains what he means by that he tells a few war stories, stories that confirm that his own discharge from that war remains incomplete. And the country? How has America been Vietnamized? For McDougall, “first out of the box was the professionalization of the armed forces.” Secondly, the American “failure in Vietnam helped to sustain a Congressional counterattack of the military prerogatives of the president.”

Then there is the “so-called Vietnam Syndrome,” which he defines as the “fear that foreign involvements could metastasize into new Vietnams.” Not yet finished, he adds one very significant positive, namely the fact that the U. S. fielded its “first fully integrated army” in that war, as well as one more very significant negative, namely the fact that the war in Vietnam triggered the “great transformation (or some would say, deformation) when ‘tenured radicals’ (began to conduct) their ‘long march through the institutions.’”

If Walter McDougall has no time for Woodrow Wilson, he also has no time for the anti-Americanism of those tenured radicals. Yes, American forces “occasionally committed war crimes in Vietnam,” but the war itself was not criminal. If anything, its motives were shockingly altruistic.” Might they even be called Wilsonian?

Yes, to borrow from the title of a previous McDougall book, the United States is a “promised land” and a “crusader state.” Like it or not, we have been both for a very long time. Sometimes we are one, and sometimes the other. And then there are times when we try to be both at once.

Like it or not, the potential conflict between the two can make it very difficult for American leaders to “do grand strategy.” Witness Woodrow Wilson–and Lyndon Johnson–or George W. Bush, for that matter. Nonetheless, Walter McDougall thinks that it can be done. Borrowing from the late Angelo Codevilla, he calls for basing American statecraft on the “American’s people’s penchant for trying to do the right thing.” Witness the statecraft of a Lincoln or Theodore Roosevelt. On the other hand, “using the American people’s righteousness as a propellant for private dream,” as did Wilson, or as a “cover for tergiversation,” as did Bush 43, is inevitably going to be “ruinous.”

Is McDougall optimistic that future American statesmen will follow the path charted by a Lincoln or TR? Not necessarily. To return briefly to the “madness of Saint Woodrow,” McDougall concludes that essay with a reference to the “surprising election” of Donald Trump in 2016. In many respects, Trump is the anti-Wilson when it comes to American matters both foreign and domestic. So far so good, McDougall must think. And yet he predicts that the “Trump phenomenon will be ephemeral.” Why? In the end Trump will “prove no more able than Barack Obama to break the spell cast by Woodrow Wilson one hundred years ago.”

Maybe, just maybe, that spell actually extends much deeper into the American past. Having promised to confine this review to five McDougall essays, permit me to reference a sixth. Titled “Meditations on a High Holy Day,” it meditates on the Fourth of July and the American civil religion, a civil religion that is embodied in the Declaration of Independence, which declaration led G.K. Chesterton to remark that the United States is the only “nation with the soul of a church.”

It’s a great line—and not simply because it is devoid of both adjectives and adverbs. In fact, McDougall himself uses that line in his “meditation” on the Fourth. But let’s give the last line to John Adams. In 1809, McDougall tells us, Adams wrote the following: “I insist that the Hebrews have done more to civilize men than any other nation. [Even if I were an atheist who believes] that all is ordered by chance, I should believe that chance had ordered the Jews to preserve and propagate to all mankind the doctrine of a supreme, intelligent, wise, almighty sovereign of the universe, which is the essential principle of all morality, and consequently all civilization.”

In 1809 we were a fledgling nation stumbling our way into yet another war with powerful England. But even then there was more than a hint that this new nation was, if not God’s newly chosen people, then, as Lincoln put it, God’s “almost chosen people.” Yes, we do think of ourselves as both a “promised land” and a “crusader state.” Here both adjectives are necessary and accurate, as well as potentially powerful and potentially troubling. Just ask Walter McDougall.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Andrieux faisant une lecture dans le foyer à la Comédie Française” (1847), by François-Joseph Heim, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.