DONALD Trump has increased the pressure on European countries, including Britain, to accept his demand for Greenland by promising escalating tariffs.

‘He’s crazy,’ said too many people who should know better.

Michael McFaul, who was US Ambassador to Russia under Barack Obama, called Trump’s idea to acquire Greenland ‘insane’ and ‘dangerous’. American talk-show host Joe Scarborough described it as ‘madness’ and ‘not an option, unless you are absolutely insane’. Canada’s Globe and Mail titled its opinion ‘Mad King Trump Would Break the World to Gain Greenland’.

Trump’s refusal to rule out military acquisition of Greenland is certainly wrong, but none of his actions or words about Greenland are crazy. His actions and words fit what he has long described as ‘the art of the deal’, the title of an early autobiography.

As applied to international relations, Trump’s art of the deal is counter-normative. It’s not multilateral, polite diplomacy. Rather, it’s transactional, leverage-driven statecraft. It may not be right, but it certainly isn’t crazy. And it’s working, in the camouflaged terms he sets for himself, so one might as well admit that his approach is rational and effective.

I give you the six steps of Trumpian international relations.

1. Start with an ‘unthinkable’ ask to shift the frame

Trump’s demands on Greenland work exactly the way his real-estate negotiations do:

open with a proposal so large and disruptive that it resets what is considered normal.

For instance, when he acquired Manhattan’s West Side rail-yards, he immediately proposed, among other things, the tallest building in the world. As he admits in the book, it would be unnecessarily expensive, but it garnered attention from journalists and thence investors and authorities (who negotiated something smaller).

Trump’s end goal does not need to be American acquisition of Greenland for him to claim it is. His opening claim changes the bounds and forces negotiation on parts of his demands.

By floating the idea that the United States might acquire Greenland, Trump forced other states to confront issues they otherwise avoid:

- The Arctic is a front-line between Western and Russian and Chinese interests;

- Nato cannot secure its widening area of operations without more burden-sharing from Europe;

- Settled arrangements should be re-negotiated when the context changes.

Suddenly, lesser concessions – expanded basing rights, investment guarantees, mineral access, intelligence co-operation – look reasonable by comparison.

That is classic Trump.

2. Make the other side reveal its exposure

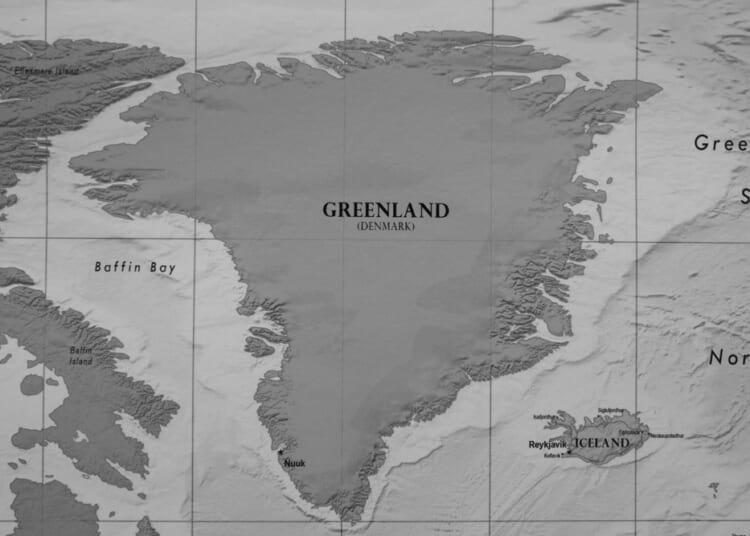

Trump’s move on Greenland exposed an uncomfortable truth: Greenland cannot be made secure without the United States. It is vast, sparsely populated and indefensible by Greenlanders alone, or the Danes, who administer island’s military and foreign affairs.

Greenland’s security relies on positive externalities from neighbours in North America, in which continent it sits geographically. These include Canadian air and sea patrols on their maritime border; the Canadian-US North American Aerospace Defense Command; wider Canadian and US activities in the Arctic Sea and Atlantic Ocean, and US military presence inside Greenland itself, such as Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base) on the north-west coast. Greenland benefits from other Nato members, and collective security agreements, principally through Denmark’s membership of Nato. But the US anchors Nato.

Do Greenlanders want to lose the shadow of US protection? Does Denmark want sole responsibility for securing Greenland?

An EU-anchored equivalent to Nato, without the US, wouldn’t substitute. The EU is too slow, incoherent, hierarchical and two-faced. Europe’s inability to cohere militarily or politically around Greenland proves, in UnHerd’s view, that Europe is ‘too weak to fight’ Trump’s demands.

Trump forced European allies, despite their explicit outrage, implicitly to acknowledge:

- Their dependence on US military power;

- Their limited capacity to act independently in the Arctic;

- Their vulnerability without the US.

Trump had already shunted Europeans most of the way in this direction years ago by threatening to withdraw US support for Nato in retaliation for European free riding.

In Trump’s worldview, leverage comes from making the other side’s exposures explicit. Traditional diplomats politely ignore such exposures, or raise them only in private.

3. Assets and liabilities

Trump speaks about sovereign territory like private real estate – as assets and liabilities. His talk is closer to 19th and early 20th century international relations. China and Russia still think that way.

By contrast, Western leaders prefer to treat territories as moral and legal abstractions. Normative Western leaders pose as internationalist, institutionalist and legalist. Trump is unapologetically patriotic, geostrategic and materialist.

Greenland attracts Russian, Chinese and American (and Nato) interest because geographically it contains or borders:

- Arctic shipping routes (growing as ice recedes);

- Shorter communications between North America and Europe and Asia, used by container ships, commercial airliners, telecommunications, intercontinental missiles, and space vehicles (which are quicker to track and intercept from Greenland during part of their journey);

- Fisheries (which account for most of Greenland’s economy);

- Rare earth minerals, which America imports from much further afield, primarily from mines owned by China;

- The Arctic landmass, which is being militarised by many states, with dependency on bases in countries within the Arctic Circle;

- One of the maritime ‘gaps’ by which Russian ships reach the Atlantic, which Nato calls the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom Gap (actually two gaps), whose security is led by Britain institutionally, but is increasingly beyond British capacity.

When Trump declares, as he did earlier this month, that America ‘needs Greenland from the standpoint of national security’, he means he wants to turn Greenland from geopolitical liability to geopolitical asset.

4. Public pressure before private diplomacy

Traditional diplomacy works behind closed doors. Trump prefers public confrontation.

By making Greenland a public issue, Trump has:

- Awakened US domestic interest in Arctic strategy;

- Forced allied governments to respond more quickly;

- Prevented the issue from being buried in bureaucracy.

This mirrors his trade tactics with China, Nato and the EU: public pressure first, private refinement later (epitomised by the so-called US-EU tariff ‘deal’ of 2025, which is really a list of intents).

5. Signal long-term intent, even if the conditions for a deal aren’t right yet

Even though Trump’s ambitions are bold, particularly when he sets the frame, he is patient and risk-averse. So he says in his book, The Art of the Deal.

‘People think I’m a gambler. I’ve never gambled in my life. To me, a gambler is someone who plays slot machines. I prefer to own slot machines. It’s a very good business being the house . . . I happen to be very conservative in business.’

Even when Trump demands all of Greenland, he’s also signalling what he wants short of the whole thing. His signals have already provoked more European involvement in Greenland’s security. That is a win by Trump’s standards. Those same signals have also put Russia and China on notice that America is sensitive to their incursions. That too is a win.

What a contrast to Britain’s long tolerance of Russian incursions into British maritime and air spaces! Britain has America to thank for the Government’s willingness this month to help the US to seize an oil tanker fleeing Venezuela under a Russian flag. Russia will be more cautious about sailing illegitimately around British waters in the future.

6. Reward and punish in other domains

Trump’s book is replete with what marketers call bundling, and what political scientists call issue linkage.

If a bank financed one of Trump’s real estate deals, he would steer other developers its way. If a real estate owner made a deal with Trump, he would support that owner’s applications to municipal authorities for other development. But if somebody thwarted Trump, he would sue, he would vote down their projects, and he would raise their costs – even those of tenants who, he thought, were lowering the tone of the building.

On Greenland, here’s an example of reward: Trump’s administration has suggested direct payments to Greenlanders upon annexation. Mooted amounts vary from $10,000 – $100,000 (£7,400 – £74,000) per resident.

Now here’s an example of punishment. On Sunday, Trump announced a 10 per cent tariff on imports from eight European nations including the UK for thwarting his intents on Greenland. He said they will start in February, and will escalate to 25 per cent by June unless his ‘complete and total purchase of Greenland’ is achieved.

Western politicians are shocked. Territorial disputes should not be linked with trade. Even Nigel Farage, Trump’s friendliest party leader in Britain, quickly stated that ‘to use economic threats against the country that’s been considered to be your closest ally for over a hundred years is not the kind of thing we would expect. It’s wrong, it’s bad.’

Still, Western politicians have already conceded to Trump in prior tariff wars which they say he started. Moreover, these tariff wars often expose the hypocrisy of his opponents, most obviously the EU, which talks about free trade but practises protectionism. It also uses tariffs to punish China for copyright infringement, price dumping and espionage.

In conclusion, Trump’s move on Greenland was a gambit, not a gaffe – not crazy, naïve, ignorant, or unserious. His process is consistent with his negotiation doctrine since he started in real estate in the 1970s.

In his The Art of the Deal diplomacy, he’s already winning some of what he wants, even if he’s losing friends.