One comes away from both F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby” and Evelyn Waugh’s “Brideshead Revisited” with an acute sense of the emptiness of the jazz age and the despair at the heart of all our delusions and decadence. One also can’t help but compare the lives of the authors themselves.

On re-reading The Great Gatsby and meeting again F. Scott Fitzgerald’s narrator, Nick Carraway, I couldn’t help being reminded of that other observer of delusion and decadence: Evelyn Waugh’s Charles Ryder.

On re-reading The Great Gatsby and meeting again F. Scott Fitzgerald’s narrator, Nick Carraway, I couldn’t help being reminded of that other observer of delusion and decadence: Evelyn Waugh’s Charles Ryder.

Carraway—a simple bond salesman from the midwest is drawn into the glittering world of the seemingly sophisticated socialite Jay Gatsby. Charles Ryder—a modest Oxford student is drawn into the opulent champagne and strawberries world of Lord Sebastian Flyte. Both stories unfold in a sumptuous setting: Gatsby’s fantastic mansion in West Egg and Brideshead Castle—the ancestral pile of the Marquess of Marchmain. Carraway observes the decadence of 1920s American “new money,” while Ryder is drawn into the decay of 1920s English “old money”. Whether the money is old or new, and the characters archaic or parvenu, the delusion and decadence compare.

Both Ryder and Carraway are attracted by the extravagant elegance of West Egg and Brideshead, but both are also curious and cautious of the deep waters into which they are plunged. Carraway is curious about Gatsby’s backstory. Ryder is fascinated by the personalities and history of Sebastian’s family. Both end up being drawn into a web of delusion, alcoholism, adultery, and deceit. Both retreat in the end from the delusion and decadence—Carraway back to being a modest bond salesman in the Midwest, and Ryder to being an solitary, but realistic soldier.

What do they (and we) learn from their observations? I think with Nick and Charles we learn about the siren songs of delusion and decadence. This world’s vanity is on display: the delights of decadence glitter with fatal allure, but vanity, vanity, all is vanity. It is a matrix of immaturity, a delusion of delight, a pablum of pleasure. Gatsby’s mansion is obviously a hollow pleasure dome, while venerable Brideshead Castle winds up as a gambling hall when the boorish Rex Mottram is in charge. Lord Marchmain’s palazzo in Venice is morally no more than a sleazy flat where a rich man houses his mistress. Sozzled Sebastian ends up in a cheap apartment with a low-life sponger, and poor old uxorious Bridey with the regrettable Mrs. Muspratt.

In the end the glitter is gone. The bubble bursts. Gatsby is murdered. Sebastian is a hopeless dipsomaniac. Julia has chosen God over Charles. Lord Marchmain has died within a whisker of damnation and Daisy, after accidentally killing another woman, slinks away with her boorish husband, “retreating into their money and vast carelessness”.

It turns out the not so great Gatsby is just James Gatz from a dirt poor farming family—and Brideshead Castle is a castle in the air. Beneath all the glitter is gritty reality. Farm boy Jimmy Gatz fled into the American Dream and the whole Flyte family were in flight from reality: Lord Marchmain to Venice and Cara—Julia to Rex and disaster, Sebastian to the bottle and Bridey to a matchbox collection and Beryl. Cordelia emerges from the bonfire of the vanities unscathed and Charles joins her taking refuge in the only reality which is his newfound faith.

One comes away from both stories with an acute sense of the emptiness of the jazz age and the despair at the heart of all our delusions and decadence. One also can’t help but compare the lives of the authors themselves.

Fitzgerald—born and brought up in an Irish-Catholic home—fell victim himself to the delusions and decadence. Living lavishly at first, his writing career took a tumble, and he ended up alone and trapped in the bottle like Sebastian. Catholic convert Waugh, on the other hand, like Charles, tasted of the strawberries and champagne, but ultimately found refuge in faith and family.

The contrast echoes in the two stories. Fitzgerald had enough depth to weave a symbol of Divine watchfulness into the story, with the billboard of the occulist (or is he an occultist?) Dr. T.J. Eckleburg presiding over the valley of ashes, but Eckleburg (along with his vision-enabling practice) is long dead, and the billboard is faded.

Waugh manages his moral neatly with a poetic “twitch of the thread”. Where Fitzgerald fails, Waugh succeeds by placing a beacon of hope at the end of his tale…

The place was half-dark and the air heavy with incense. The sanctuary lamp was relit before the beaten-copper doors of a tabernacle; the flame which the old knights saw from their tombs, which they saw put out; that flame burns again for other soldiers, far from home… and there I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones; I ventured to say a prayer, an old agnostic prayer: ‘O God, make me good, make me good.’

_________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

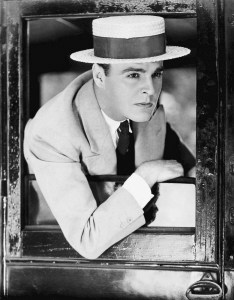

The featured image is “Publicity still from The Great Gatsby 1926 promoting Neil Hamilton as Nick Carraway” (21 November 1926), and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.