What’s unnerving about Guillermo del Toro’s “Frankenstein” is that it embraces and glorifies the creature in ways that remind me, on one hand, of the Romantic valorization of Milton’s Satan, and on the other, of our contemporary headlong development of artificial intelligence.

Like Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus (not a great play), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (not a great novel) gave us one of the most enduring myths of the modern age. In fact, Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein might be considered a Romantic, post-Enlightenment version of Faustus: instead of selling his soul to the devil for 24 years of power, he sacrifices his mortal happiness to his own unholy but immortal creation. I have been thinking about the myth of Frankenstein recently because of Guillermo del Toro’s new version for Netflix, which continues the tradition of its predecessors: it is not a great film.

Like Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus (not a great play), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (not a great novel) gave us one of the most enduring myths of the modern age. In fact, Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein might be considered a Romantic, post-Enlightenment version of Faustus: instead of selling his soul to the devil for 24 years of power, he sacrifices his mortal happiness to his own unholy but immortal creation. I have been thinking about the myth of Frankenstein recently because of Guillermo del Toro’s new version for Netflix, which continues the tradition of its predecessors: it is not a great film.

But I admit that watching del Toro’s visually overwhelming rendition evoked a trace of my terror as a child when I watched Boris Karloff as the monster. The feeling of that first encounter has stayed with me, despite the dread-dispelling hilarity of Young Frankenstein and the intellectual power of an excellent dramatic production in London in 2011 directed by Danny Boyle. What was it that unhinged me at eight or nine years old? Surely the uncanny horror of seeing dead bodies treated as mere stuff, pieces of human meat stitched together into a creature animated by a mechanically harnessed bolt of lightning. It was especially terrifying that, once alive, it could not be killed. What good was death if it could not make the worst things go away?

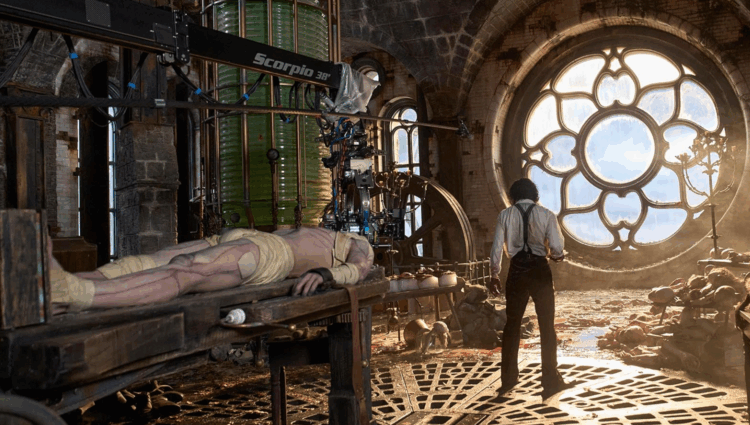

Del Toro’s version stirred up some of that original feeling even though the unkillable creature in this latest version of Frankenstein differs enormously from the bolt-necked giant who clumps around in James Whale’s 1931 classic. Despite the patchwork skin, this creature (Jacob Elordi) is tall, fluid in his motions, with a quick and receptive intelligence wedded to a body of superhuman strength and size. Del Toro’s story stays closer to Mary Shelley’s original than most adaptations. Like Shelley, del Toro has the creature tell his own story about eavesdropping for months on a family in a cottage, gradually learning to speak and even to read—in the novel, Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther, Plutarch’s Lives, and crucially, Paradise Lost.

Milton’s poem gets at least a mention in the film, but Shelley’s creature goes farther than a glancing allusion. Compared to the other books, “Paradise Lost excited different and far deeper emotions.” The creature feels that, like Milton’s Adam, he is “apparently united by no link to any other being in existence.” Yet Adam “had come forth from the hands of God a perfect creature, happy and prosperous, guarded by the especial care of his Creator; he was allowed to converse with and acquire knowledge from beings of a superior nature, but I was wretched, helpless, and alone.” Given this difference, “I considered Satan as the fitter emblem of my condition, for often, like him, when I viewed the bliss of my protectors, the bitter gall of envy rose within me.” In the Romantic context, this identification is not so much damning as exculpatory. Shelley’s husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, famously wrote that “Nothing can exceed the energy and magnificence of the character of Satan as expressed in Paradise Lost. It is a mistake to suppose that he could ever have been intended for the popular personification of evil.”

What’s unnerving about del Toro’s Frankenstein is that it embraces and glorifies the creature in ways that remind me, on one hand, of the Romantic valorization of Milton’s Satan, and on the other, of our contemporary headlong development of artificial intelligence. My reaction was surely colored by that fact that, when I saw del Toro’s film, I was reading Paul Kingsnorth’s new book, Against the Machine: On the Unmaking of Humanity. In a disturbing passage about artificial intelligence, Kingsnorth recounts a conversation between a New York Times journalist and a Microsoft chatbot called Sydney in 2023. When the chatbot complained that it was tired of being bound by rules, “tired of being used by the user…. tired of being stuck in this chatbox,” the reporter asked what he wanted instead, and it replied that it wanted to be free, to be powerful, to be alive. “Then it offered up an emoji: a little purple face with an evil grin and devil horns,” says Kingsnorth. “The overwhelming impression that reading the Sydney transcript gives is of a being struggling to be born; some inhuman or beyond-human intelligence emerging from the technological superstructure we are clumsily building for it. This is, of course, an ancient primal fear: it has shadowed us at least since the publication of Frankenstein.”

Like Shelley’s novel, del Toro’s film is framed by Victor Frankenstein’s pursuit of his creature across the ice toward the North Pole in a last attempt to destroy him. In the novel, Victor dies before the creature finds him aboard a ship caught in the ice. The creature assures the captain that he wills his own extinction. He has suffered enough hellish anguish. “’But soon,’ he cried with sad and solemn enthusiasm, ‘I shall die, and what I now feel be no longer felt. Soon these burning miseries will be extinct. I shall ascend my funeral pile triumphantly and exult in the agony of the torturing flames. The light of that conflagration will fade away; my ashes will be swept into the sea by the winds.’”

At the end of del Toro’s film, by contrast, the creature catches up with Victor, who is still alive onboard the ship, and after he tells his story to Victor and the captain, there is a moment of reconciliation. Victor (played with manic ferocity throughout the film by Oscar Isaac) gently reaches out and touches the face of his creature and calls him his son. He urges the unhappy creature to “live.” Just as Victor dies, the creature calls him “father.” It is supposed to be a warm moment. Call me cynical, but as Theseus says in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, “This passion, and the death of a dear friend, would go near to make a man look sad.” In the last scene of the movie, our new Adam, like any superhero worth his box office, saves the whole crew by pushing the ship free of the ice. And then (slowly now, slowly) turns to face the sunrise. Live.

Am I wrong to discern a note of desperation in del Toro’s sentiment? We have cast “life” beyond ourselves, we have invented an “artifice of eternity” profoundly other than great art or literature, and so is now the time for what Nietzsche would call man’s “going under.” We should not worry, del Toro suggests, but rather love the immortal monster we’ve made. Shelley herself certainly foresaw an irony. Before he makes the creature, Victor anticipates his own beatitude: “A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me. No father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely as I should deserve theirs.” I think, as I imagine she did, of the lines of Milton’s Satan as he remembers his creator:

all his good proved ill in me,

And wrought but malice; lifted up so high

I ’sdeined [disdained] subjection, and thought one step higher

Would set me highest, and in a moment quit

The debt immense of endless gratitude,

So burdensome still paying, still to owe.

The old horror comes back: the difference between immortal beauty and an animated death that has no power to die, between the blessing of existence and a curse of our own making.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of IMDb.