In this materialistic age, time has become a commodity that can be bought and sold. This is evidenced by the place that the monetization of time holds in common parlance: “spend your time well,” “I have some free time,” “time is money,” etc. It is tragic to see time itself be corroded by the greed of modern man. In ages past, time was known to be sacred; it was the means by which the movements of the heavens were measured, and ultimately it was agreed to be a gift from God (or the gods). But from the sin of those who have enslaved time, a grace can spring forth. That same wisdom by which Aristotle described the virtue of magnificence can be applied to the “spending” of time and yield a new species of magnificence.

In this materialistic age, time has become a commodity that can be bought and sold. This is evidenced by the place that the monetization of time holds in common parlance: “spend your time well,” “I have some free time,” “time is money,” etc. It is tragic to see time itself be corroded by the greed of modern man. In ages past, time was known to be sacred; it was the means by which the movements of the heavens were measured, and ultimately it was agreed to be a gift from God (or the gods). But from the sin of those who have enslaved time, a grace can spring forth. That same wisdom by which Aristotle described the virtue of magnificence can be applied to the “spending” of time and yield a new species of magnificence.

The Virtue of Magnificence: Money

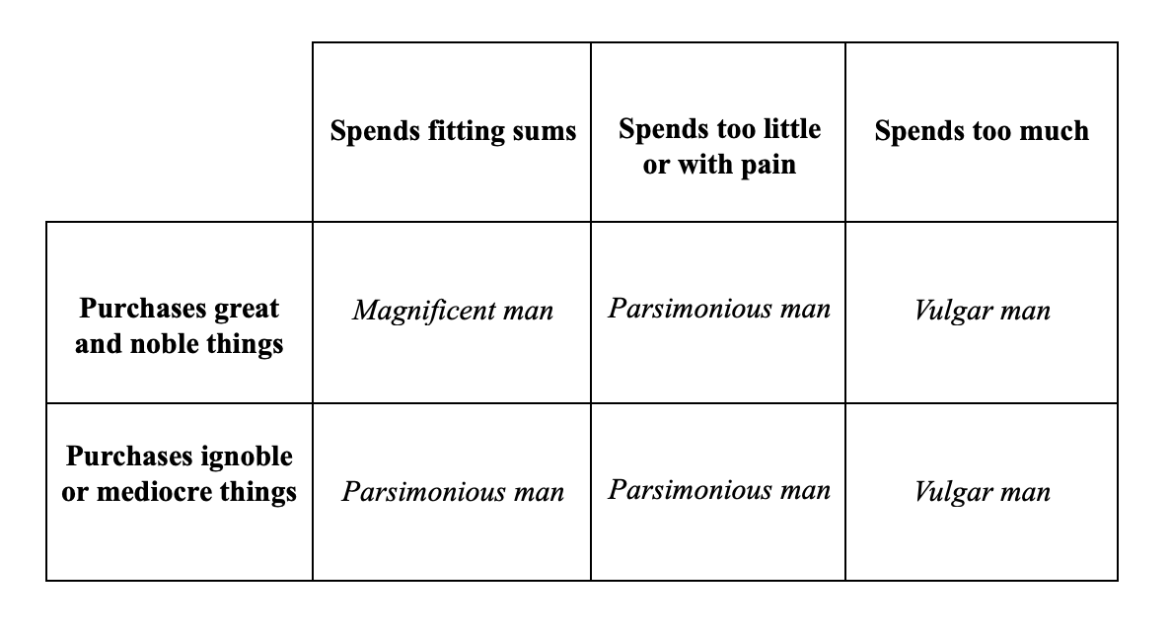

In the second chapter of the fourth book of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle wrote about the virtue which he called magnificence. He defined this virtue, using monetary terms, as “a fitting expenditure on a great thing” (1122a 22-23). He situates magnificence as the means between the vices of parsimony and excessiveness or vulgarity (1122a 30-32 and 1123a 20).

In one sense, the virtue of magnificence is objective, for the magnificent man spends a suitably significant sum of money to buy great things. As such, he is necessarily liberal with his material goods, but the liberal man is not necessarily magnificent (see 1122a, 29-30). Objectively, the magnificent spender must possess the capital to spend a great sum to acquire great and noble objects.

In a second sense, magnificence is subjective as it requires prudence. A great purchase can either be virtuous or vicious. For a poor man to spend a large sum is foolish, but for a rich man, it can be virtuous (see 1122b 27-29). The mere expenditure of a great sum is not virtuous. A man who spends small amounts of money on things of modest value may be said to have gotten a good deal or to be a man of some prudence. This prudent purchase is a fitting expenditure on a mediocre thing rather than a fitting expenditure on a great or noble thing.

Aristotle further nuances this virtue as he goes on to say that “what is great in the case of a given work differs from what is great in the case of the expenditure, for the most beautiful ball or oil flask is magnificent as a gift for a child, though its cost is small and cheap” (1123a 13-15). This might seem to undermine what has been said above, for here he has asserted that it is magnificent to purchase that which is inexpensive. Nobility does not lie in the price tag. Nor does it lie in the object itself. Rather, it is a relative to the person involved and a balance between the inherent value of the thing and the value assigned to the object by the recipient and the men of the age (see 1122a 25-27 and 122b 24-27).

One extreme expenditure is the vice of excessiveness or vulgarity. What is meant by this is any man who spends beyond what is fitting or spends merely as a display of wealth (1123a 20-26). Magnificence is not the mere spending of great sums, but the rightly ordered spending of fitting sums and great and noble things. Should the rich man spend a great amount of his wealth, but the object purchased is of little or no value, he would not be counted as magnificent—he would be known as a vulgar fool. Any expenditure that is not done for the sake of the noble cannot be said to be magnificent.

Whether a great or a small amount is spent, this virtue requires that the man is not so attached to his money that it greatly and visibly pains him to be separated from it; this love of money is the defect of parsimony (1123a 30). The man who spends a fitting amount on small or measured things is also said to be parsimonious (see 1122a 27-31). Simply put, the penny pincher cannot be said to be magnificent.

To the definition of “a fitting expenditure on a great thing,” Aristotle adds a few qualifications. First, there is a certain pomp and circumstance that surrounds the Aristotelian virtues that modern Christians might often associate with vainglory. The magnificent man should not hide his magnificence. Virtue should shine forth and illuminate the world, and—as the Evangelist would say—it should not be “hidden under a bushel.” As was noted above, the display of wealth for the sake of displaying wealth is vulgar.

Second, Aristotle notes that the magnificent man is not a hoarder; while he furnishes his house in a manner befitting his health, he uses his health to show his genuine concern for the common affairs (see 1123a, 5-9). The magnificent man suitably spends fitting amounts of money on great and noble things.

The Virtue of Magnificence: Time

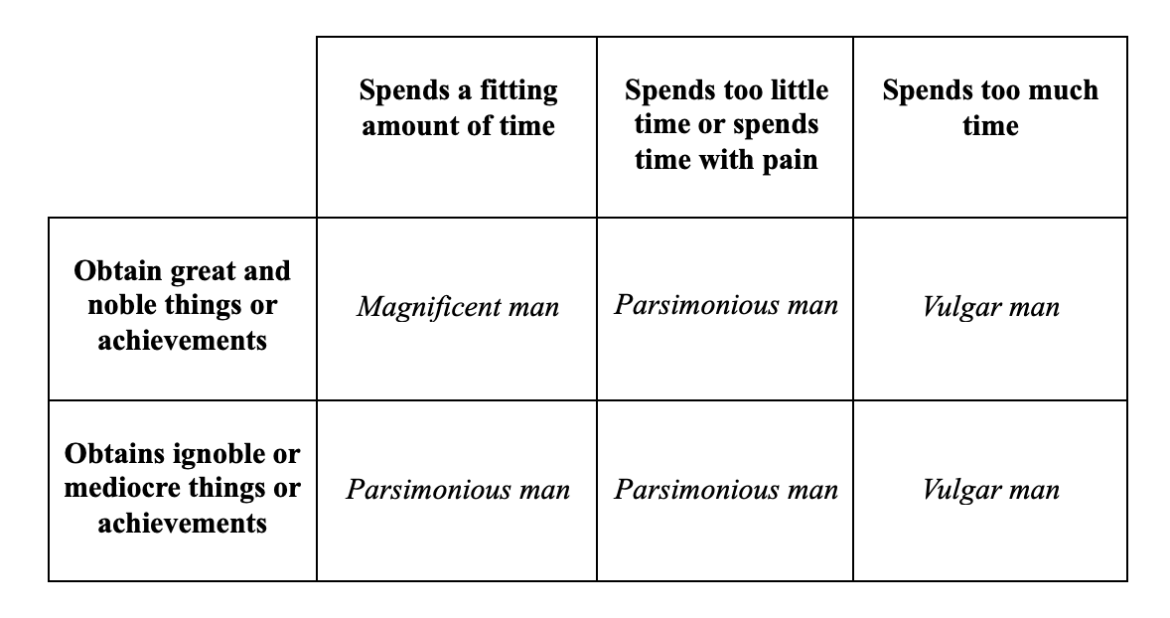

All of what has been said above concerning monetary expenditures can be applied to the way in which one “spends” his time.

There is a certain objective sense in which magnificence requires temporal liberality and temporal wealth. To achieve great things, a significant amount of time will need to be available. The end of a great temporal expenditure must be great and noble. Temporal magnificence leads to the acquisition of great things or achievements. A great amount of time is spent on acquiring a doctorate, raising virtuous children, or becoming a pianist. Each of these bold expenditures has the potential to be a fitting temporal expenditure in a great thing or achievement.

There is also a subjectivity and a prudence required by this magnificence. The mere possession of a free schedule does not equate to magnificence. Spending many hours on something that is ignoble or mediocre cannot be termed magnificent. No one would tally the hours he spent watching YouTube shorts can call himself a magnificent man because he has spent innumerable hours rotting his brain out. To overspend one’s time on ignoble or mediocre things falls short of the virtue. In the direction of the other extreme, a person would be temporally parsimonious if he were so tied up in his schedule that he did not spend his time on anything great or noble. Likewise, if he, being so tied up, only spends his time on noble things at great pain, he would be a temporal penny pincher and fall short of the virtue of magnificence.

Overspending time on great and noble things falls into the domain of vice. Should one attempt to obtain a doctorate at the expense of his necessary employment or of his care for his family, he would be a vulgar man. This would not be a fitting temporal expenditure.

Temporal magnificence requires the normal pomp and circumstance of Aristotelian virtues. He who hides the temporal expenditure required to obtain a doctorate, virtuously reared children, or skill as a pianist does himself a disservice, omitting his well-earned glory. Likewise, he who hides these great and noble accomplishments does a disservice as he fails to demonstrate concern for common affairs—he hoards his time.

Whether significant or insignificant amounts of time are devoted to ignoble or mediocre ends, the man who spends this time embodies the vices of vulgarity or parsimony. Magnificence can only be attained by freely and prudently spending a fitting amount of time on a great or noble end.

While this understanding of the magnificence of time does not return the common parlance of understanding time as sacred, it provides an understanding of virtue, enabling man to be magnificent. That same wisdom by which Aristotle described the virtue of magnificence can indeed be applied to the “spending” of time and yield this new species of magnificence. Time is not merely a commodity to be bought and sold; by its monetization, it has become a source of magnificence.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Allegory of Magnificence” (circa 1654), by Eustache LeSueur, Dayton Art Institute, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.