‘HAMLEYS puts Lego bricks on the greatest toys of all time list . . . Lego is a timeless, creative phenomenon.’ ‘Lego is the best toy ever invented.’

The Danish phenomenon is the last page (so far) in the centuries-old story of toy building-brick invention and development. Much less known are the earlier chapters showing that the Lego brick was an almost exact copy of a British inventor’s design nearly 100 years ago.

Children’s building blocks in various shapes, sizes and materials have been around for several hundred years. Most were simple wooden cubes or other shapes which stacked one on top of the other but a slight blow would demolish the pile.

The next stage was to make them interlocking; they would then stack safely in a tower although still not really stable.

An American company’s Bild-o-Brik seems to have been the first to use a self-locking brick in the early 1930s. The pieces had studs on one side which would fit into holes on the other. They used rubber rather than wood and the studs were slightly larger than the holes so the interlocking would be firm.

This development must have been noticed by Arnold Levy, the founder of the Premo Rubber Company in Petersfield, Hampshire, on one of his trips to the US in the mid-thirties. The company produced a new design of the brick in 1935 which with its studs and holes was now beginning to look like a Lego antecedent.

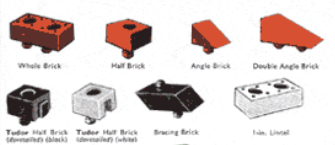

Courtesy of Minibrix/Premo Rubber Co

The basic brick was 1″x½”x⅜”. The patent for the new designs was applied for in July 1935. By the late 1930s eight different sets were available, from 5/- to £3/3/0 (25p – £3.15, while the average wage was around £3 a week).

I had a box of Minibrix for Christmas 1938. I was so pleased with its versatility that I wanted more, but was bitterly disappointed when I found out the company had gone over to war work in 1939. By the time the sets returned late in 1947 I had even grown out of Meccano.

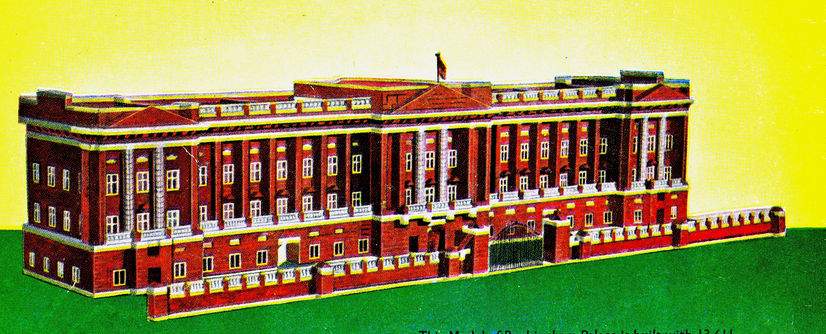

They advertised widely, using large models. One of Buckingham Palace, over six feet long, containing 13,600 pieces, went to Canada in connection with the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1939.

Courtesy of Minibrix/Premo Rubber Co

By 1937 Hilary Page, who had founded the British Kiddicraft Company in 1932, https://www.hilarypagetoys.com/Home/Products/9/740 had realised that colourful plastics would be much better and more hygienic than either wood or rubber for children’s building blocks. He bought an injection moulding machine from R H Windsor, London, and his first design was for interlocking plastic cubes, which because of the studs meant that building towers was no longer quite so infuriating when you misjudged the last one and they all fell down in a heap. Patent for this design was granted in 1940.

Kiddicraft Interlocking Building Cubes 1939 Courtesy of Kiddicraft

Page would have realised the advantages of the much better self-locking concept of Minibrix. Intensive research resulted in his own plastic version: the Kiddicraft self-locking bricks which had a four or eight stud version. He applied for a patent for this design in 1944, number 587206. A slightly later version, 633055, shown below, had slots cut in the end of the bricks to increase the locking ability.

Courtesy of Kiddicraft

Sets of these self-locking bricks went on sale in 1945 and were featured at the Earl’s Court Toy Fair in May 1947.

Courtesy of Kiddicraft

Compare that picture with this one of Lego bricks.

The Lego history website explains that the firm was founded in in 1932 by Ole Kirk Christiansen, deriving its name from the Danish phrase leg godt, meaning ‘play well’. It started by making wooden toys, but ‘by the end of World War II, Ole Kirk Kristiansen was finding it increasingly difficult to source beechwood of the right quality’, so turned to plastics and ordered an injection-moulding machine from R H Windsor (yes, the same company that Page used), which was in Denmark by December 1947.

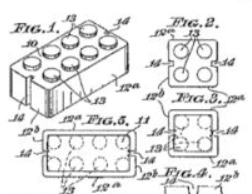

The Windsor sales rep took with him some of the Kiddicraft bricks to show what could be done on their machine. The 1997 Lego publication Developing a Product* explains what happened next. ‘Automatic Binding Bricks . . . were inspired by a couple of British plastic building bricks made by the Kiddicraft company . . . we modified the design of the brick [including] straightening round corners and converting inches to cm and mm, which altered the size of the brick by approx. 0.1 mm in relation to the Kiddicraft brick.’ Production started in 1947.

Now for an inexplicable chapter in the story. It seems that Lego were worried about the very noticeable similarity between their design and the Kiddicraft Self-Locking brick. They say they got in touch with Hilary Page in the late 1950s and asked if his company had any objection to their design. According to the Lego history website the company said no. It continues: ‘On the contrary, they [Kiddicraft] wish the company good luck with the bricks, as they have not enjoyed much success with their product.’

In 1981 Lego ‘agreed an out-of-court settlement of £45,000 for any residual rights of the new owners of Mr Page’s company, Hestair-Kiddicraft’. Hilary Page had taken his own life in 1957, so he was never to see how Lego realised the vast potential of the plastic self-locking brick idea.

The modern Lego brick is a result of a redesign in the 1950s. The underside now has tubes to give the studs a better grip. It was recognised as ‘Toy of the Century’ by several organisations in 2000.

Here is yet another British invention that was copied by a foreign company, then with a great deal of development work, a careful attention to detail and a far-sighted realisation of its potential, Lego became a world-renowned concept.

Not just a toy any more, but a gift for the imagination and challenge for your dexterity. Just a shame that when the bricks are scattered over the floor that the sharp edges have hurt so many careless feet. Page’s bricks had a rounded edge.

*This extract is quoted in The Place of Play: Toys and Digital Cultures, Maaike Lauwaert, Amsterdam University Press, 2009, pages 51-52.