The music of little-known Baroque composer Francesco Antonio Bonporti embodies a kind of Arcadian serenity and joy, like the music of Mozart. Art conceived along those lines is closely tied to the refinement of the spirit, in which the senses do not go their own brutish way but are reconciled with the mind by means of good taste.

Francesco Antonio Bonporti o la fede sonora: Conversazioni impossibili con un compositore barocco, by Alberto Nones (Notami, 104 pages, 2020)

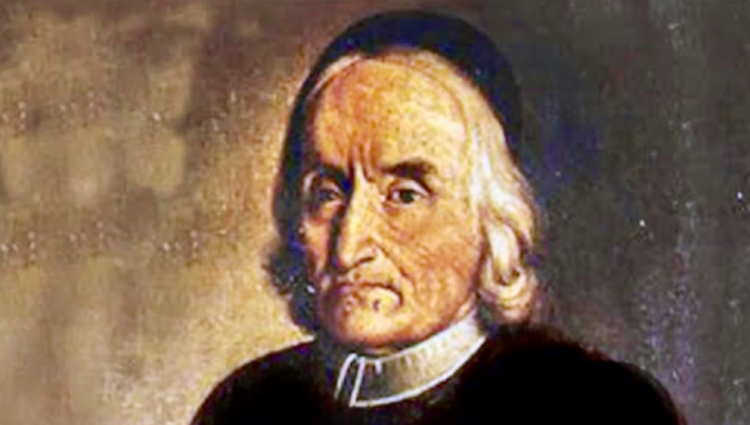

There is a sad feeling that comes when you experience an exceptionally fine book, piece of music, or work of art, and realize that only a small number of people on earth will ever know about it. I had such a feeling on reading the book that is the subject of this review essay, a book whose title translates as Francesco Antonio Bonporti, or Sonorous Faith: Impossible Conversations with a Baroque Composer. There are two principal reasons why this book will have a small audience. One is that it is in Italian. Another is its rather specialized topic: the Italian Baroque composer Francesco Antonio Bonporti (1672–1748), who is not a household name even among classical music aficionados. But the book’s narrow focus is deceptive; it embraces a wide range of subject matter, cultural, philosophical, and theological as well as musical and aesthetic. If it were ever translated into English, I think it would appeal to a wide audience of intelligent readers, imaginative conservatives included. Let me explain why.

There is a sad feeling that comes when you experience an exceptionally fine book, piece of music, or work of art, and realize that only a small number of people on earth will ever know about it. I had such a feeling on reading the book that is the subject of this review essay, a book whose title translates as Francesco Antonio Bonporti, or Sonorous Faith: Impossible Conversations with a Baroque Composer. There are two principal reasons why this book will have a small audience. One is that it is in Italian. Another is its rather specialized topic: the Italian Baroque composer Francesco Antonio Bonporti (1672–1748), who is not a household name even among classical music aficionados. But the book’s narrow focus is deceptive; it embraces a wide range of subject matter, cultural, philosophical, and theological as well as musical and aesthetic. If it were ever translated into English, I think it would appeal to a wide audience of intelligent readers, imaginative conservatives included. Let me explain why.

First of all, the book is engaging and full of charm. The author, Alberto Nones, is an Italian musicologist who has constructed a set of imaginary conversations with Bonporti, a priest as well as a violinist and composer who was a contemporary of Vivaldi, Handel, and Bach. Uniquely among composers, Bonporti hailed from Trento/Trent, the northern Italian city famous for its alpine scenery and as the site of the famous church council which continues to influence us today.

Nones is also from Trento, and he is devoted to studying the city’s native musical son. In the book, Nones imagines a seven-day series of conversations with Bonporti conducted in Trento’s town square. (How Bonporti got here, whether by séance or time machine, is never explained.)

My sadness is double, because not only will few people read this book, but few will hear the music of Bonporti, one of many secondary geniuses of the Baroque. Given his priestly duties, Bonporti’s musical output was small and includes works for violins and other string instruments, and sacred motets. I have played his violin pieces with great pleasure. After his death, Bonporti lapsed into obscurity and was only rediscovered in the 20th century as part of the Bach revival (similarly to what happened with Antonio Vivaldi). Bach, you see, arranged some of Bonporti’s violin pieces for harpsichord, and these were mistaken for original compositions by the German master. When a musicologist discovered that they were in fact transcriptions from Bonporti, it opened a door to an unknown composer. Today, while it would be a stretch to say that Bonporti is on anyone’s top-10 list, he has a recognized place in the pantheon of his time and place.

The idea of a priest being also a composer, or a creative artist of any sort, is a foreign concept today. Yet Bonporti combined the two vocations quite nicely, and the deepest parts of the book are those in which the composer discusses his spiritual artistic credo. It is, in short, a vision of music as a reflection back to God of the perfection and beauty of God’s own creation. For Bonporti, man is inherently a faber, a maker. Mankind betrayed God’s trust by falling into sin, hence the necessity to regain his original dignity through honest work, including artistic work. As Bonporti puts it in the book, “With music we magnify, even if a little bit, the greatness of the Creator. All with sound!” Art itself is nothing but “an ornament to God’s handiwork.” And in another place: “Music is sound that comes from God, we do nothing but transmit it on earth.”

In Bonporti’s day the Church was the patron of the arts par excellence. Through a host of factors this is no longer the case, and the art world and the world of spirituality and religion could not be further apart. On one side, the world of the arts has become extremely secularized and academic—thus, irrelevant and remote from the average person. On the other side, the world of religion has largely divorced itself from the concerns of art and aesthetics (for an example just look at many modern buildings of worship). In such a fragmented environment, putting art and theology, or aesthetics and belief, back together would seem the most viable approach to making art meaningful.

Bonporti’s music, says Nones, embodies a kind of Arcadian serenity and joy, which he terms an “aesthetic of positivity” and which he also identifies in the music of Mozart, a generation or two later. This part of the Impossible Conversations was particularly interesting to me, for I have often recognized, and enjoyed, such an aesthetic approach in the work of many artists in diverse fields. One of the best articulations of the aesthetic of positivity that I know comes, of all places, from the Golden Age film star Greer Garson. It is a wonderful quote which I happily reproduce here: “I think the mirror should be tilted slightly upward when it’s reflecting life—toward the cheerful, the tender, the compassionate, the brave, the funny, the encouraging, all those things—and not tilted down toward the gutter part of the time, into the troubled vistas of conflict.”

Art conceived along those lines is essentially classical, constructing an ideal inner world through the imagination. It is closely tied to civility, with what the fictional Bonporti calls “the refinement of the spirit, in which the senses do not go their own brutish way but are reconciled with the mind, by means of good taste.”

This is the approach to beauty that we hear in the music of Bonporti and, to be sure, Mozart. But how does this differ from the musical aesthetic of Bach, or Beethoven? Bach’s music projects a sense of cosmic creation; I seem to see planets and suns spinning in space when I hear Bach. It is elemental, primal, and divine. Mozart’s music is human, warm, and endearing. And Beethoven? He seems to assimilate both the aesthetic of divine creative power (call it the Promethean quality) and the aesthetic of positivity and humanity, and adds to it a new emphasis on personal expression, a hallmark of Romanticism.

The possibility that differences in aesthetic might reveal differences in national and/or religious culture is also touched upon in the Impossible Conversations. Nones asks for Bonporti’s opinions on his illustrious contemporary to the north, Johann Sebastian Bach. Bonporti admits that Bach was little known in his day, a startling assertion that reminds us of the drastic changes in the assessment of artists and musicians through the ages.

Not only that, but the German dominance in classical music that we take for granted today (think of Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Mahler…) was something that developed later. In Bonporti’s day, it was Italy that held undisputed sway in the musical field, as can be seen in Bach’s admiration of his Italian contemporaries including Bonporti himself. But what of the aesthetic difference between the German and the Italian?

Nones puts his finger on the difference when he describes Bach’s music as having a “solidity” and “gravity” in which “every note has its specific weight and necessity.” Bach’s music presents a multitude of notes in a complex contrapuntal arrangement sounding to the glory and richness of creation. Each note is like an individual stone in a magnificent Gothic cathedral.

But Bonporti hears in all of this a kind of “German rigidity.” He himself studied in Innsbruck, Austria and experienced the German character and ethos firsthand. But then he went to Rome to study theology and felt that a wider world had opened to him, a world that was “much more open and complete” and in a word, “Catholic.”

This opens up large and fascinating cultural topics. I would argue that Bach’s art is not merely Lutheran, not merely German, but gathers up a universal sense of Christianity and Western culture. He soaked up and transformed all the influences around him, including the Italian music he so admired (like Bonporti’s), assimilating it into a grand synthesis informed by his German genius. Like the greatest art Bach’s music not narrow and provincial, but broad and all-encompassing.

The “aesthetic of positivity” sees art as a means of conveying solace, comfort, and peace to a troubled world. How different from the “aesthetic of contentiousness” (a term I invented just now) that has overtaken much of the art world in modern times, in which art is used to shock the sensibilities, to unsettle and disturb in the name of unrestrained self-expression. The artistic ego that informs so much of the modern art world is already recognized by Bonporti as having seeds in the spirit of the Enlightenment (l’Illuminismo) and, before that, what he calls the “pernicious Protestant Reformation.”

The less individualistic attitude toward art in Bonporti’s era is shown in the weaker value placed on originality and author’s rights, compared to the importance such concepts have in our day. Indeed, Bonporti professes not to care a whit that Bach appropriated his term “inventions” for his own short contrapuntal harpsichord pieces. For Bonporti, artistic ideas are a common property of creative humanity, not the exclusive possession of an individual artiste.

Another issue is the temptation, for the artist rooted in a religious ethos, of seeing his art as a means to self-centered glory and fame and advancement in this life—a temptation to which Bonporti admits he was not immune.

Bach habitually signed his manuscripts with the letters SDG for Soli Deo Gloria—“to God alone be glory.” On its face, the motto is an expression of humility, deflecting glory from the artist to the source of his talent, God. Yet Bonporti puts the motto into question as implying a denial of the corporate, intermediary emphasis of Catholicism, the ways in which God refracts his glory in creation—in the saints, notably, and in particular the Mother of Christ.

Ironically, a single-minded devotion to the divine can go along with a kind of prideful ego, as one can see in the career of Luther. And the artist will always be tempted to put his ego and the desire for success and fame ahead of the high spiritual ideals which he serves. Yet such pride can be a double-edged sword. Bonporti angled for social advancement and higher rank, and a wider recognition of his music. Yet this ambition paid off in a spiritual way, for it allowed him finally to become a dilettante, a person who wrote music for the sheer delight of it and not to make a living. Such leisure also allowed him to create the kind of music his inner artistic vision dictated, instead of merely following fashion or pleasing a patron.

Bonporti, in other words, was a completely free artist, with a kind of independence that many later composers (such as Mozart and Beethoven) struggled to achieve. And his artistic independence came from the fact that he served a higher “employer,” namely God. Nones recalls the sad case of many musical “professionals” of today, who live under the pressures of a job and for whom “making music becomes a torture.” Philosophically, we cannot but agree that Bonporti’s way is more consonant with the very nature of art.

The Impossible Conversations also touch upon the value of skepticism and the Enlightenment. The French philosophes were just coming on the scene in Bonporti’s later years, and as a conservative man of the Church and upholder of the Council of Trent (“the good old times”), he does not look upon them kindly. “Is theology not rational?” he asks.

Nones for his part gently chides Bonporti for his excessive faith in certitudes handed down by tradition, explaining that the modern spirit (formed by the Enlightenment) is one of inquiring skepticism. Nones argues that such skepticism has been a benefit to modern man, and a necessary evolution, something that was bound to happen. Bonporti counters: Has all this liberation really made you happy?

A literary conversation can be a way of presenting multiple points of a view in a dynamic format. And when the subject is historical, this might invite a clash (comic or poignant) between the past and the present, and an acknowledgement of the limitations as well as the glories inherent in the past. Here is what I am leading up to: In the course of the conversations, it comes out that Bonporti believes in the legend surrounding St. Simon of Trent and the anti-Jewish “blood libel,” a lamentable series of events in the 15th century. Nones sets Bonporti straight about the facts of the case, namely that the Jews of the city of Trent were scapegoated for the death of a Christian child. He also brings Bonporti up to date on the position of the modern Catholic Church vis-à-vis antisemitism.

Nones draws the lesson that “everyone is inescapably the child of his time, for good and bad.” Far from being anti-tradition, such an approach seems to me deeply traditional in that it acknowledges the purifying force of time and knowledge on the human understanding.

Ultimately, the tension between rationalism and faith throughout the book is resolved in Bonporti’s music itself, which is an expression of a Christian and Catholic humanism: “human, not ascetic; devout, but gracious, not fanatical.” Like the great Renaissance saint Philip Neri, Bonporti used the splendor of art and beauty to praise God and edify mankind.

The Impossible Conversations is, as the author describes it, “a conversation of vast range, holding together three centuries.” Each day/conversation is concluded with a visit to a local café to enjoy, not coffee, but hot chocolate (Bonporti declines coffee as it was invented by the Turks!). This conviviality sums up the warmth and good-natured understanding that characterize the book. Nones shows us the power of imaginative literature—and in particular the dialog format, which has done useful work since Plato—to reveal ideas and human character. The fictional Bonporti is stern, cranky, traditionalist, and full of Latin adages for very occasion: in every way a plausibly drawn historical character. The conversations are themselves like music and show us the beauty of civilized discourse.

A literary work that points toward and illuminates music is a rare thing. Nones’s little book points toward music as a portal to history and ideas. Listening to a historical work of music can become an opportunity for a kind of aural grace, as we literally “hear” the past, an essence of beauty that animated and moved our ancestors at a particular time. Music, no less than literature or painting, conveys the history of thought and sentiment, and the evolution of human culture.

The “minor musician” has suffered an unfair fate compared to the minor poet or painter. The classical music world likes to gather around a constellation of “masterpieces” produced by a small group of “immortal geniuses.” Not least of Nones’s accomplishments in Imaginary Conversations is that he vindicates one “minor” composer as a worthy satellite encircling the major suns of an era.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a portrait of Francesco Antonio Bonporti, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.