Longer-lived than most composers, Georg Philipp Telemann was still creating and experimenting in his 80s, ready to welcome the new Classical era represented by Haydn and Mozart. In some ways Telemann was the key composer of the high Baroque era, one who amalgamated all the styles of the day in a style that reflected geniality, civility, and good humor.

I am listening right now to the Melodious Canons for flute and violin by the German Baroque composer Georg Philipp Telemann. A canon, as many will be aware, is a musical form in which two or more voices or instruments perform the same melody but at different times. The melody “echoes against itself,” a technique that requires skill and imagination to pull off. As I listen, I am marveling at the ingenuity of Telemann’s art, and it occurs to me that Johann Sebastian Bach would have been proud of his contrapuntal skill. Yet complexity is not the main thing: the canons remain “melodious,” concealing their art under a carefree surface.

I am listening right now to the Melodious Canons for flute and violin by the German Baroque composer Georg Philipp Telemann. A canon, as many will be aware, is a musical form in which two or more voices or instruments perform the same melody but at different times. The melody “echoes against itself,” a technique that requires skill and imagination to pull off. As I listen, I am marveling at the ingenuity of Telemann’s art, and it occurs to me that Johann Sebastian Bach would have been proud of his contrapuntal skill. Yet complexity is not the main thing: the canons remain “melodious,” concealing their art under a carefree surface.

During his lifetime Telemann (1681–1767) was the most famous and esteemed composer in Germany, whose music was considered more modern, more progressive and à la mode than Bach’s. At one point Telemann and Bach both applied for the same musical job in the city of Leipzig. When Telemann dropped out of the running, the city fathers reluctantly hired Bach; their comment was that since the best (i.e., Telemann) could not be had, the second best (i.e., Bach) would have to do.

History, of course, has reversed the verdict: today Bach is judged a transcendent genius, Telemann a skilled craftsman who aimed to please. Yet thanks to the early music movement of the last half-century, Telemann’s music too has received a new airing. And as we get to know it better, we can hear its genius, its charm, and its value.

Our habit of drawing up rankings and making invidious comparisons in art is unfortunate. The High Romanticist aesthetic was with us for a long time, and it dictated that artists who aim for popular appeal are denigrated as inferior. Starving in a garret and writing masterworks for posterity was preferable to having a successful career and being well beloved in the meantime. Mendelssohn, a composer whose music and life radiated happiness, has likewise suffered belittlement in comparison with the stormy geniuses of Romanticism. As for Telemann, his life was not always blissful. His first wife died in childbirth, and his second was addicted to gambling and abandoned him for an army officer. The composer had to adapt to changes in musical fashion, from the heavier and complex Baroque to the lighter “gallant” style of the Enlightenment. In his later years Telemann suffered from failing eyesight (an occupational hazard, and an ailment that also afflicted Bach and Handel).

With the revival of Telemann has come a more balanced appreciation of music in general. We are more likely, now that all of cultural history is available to us, to see artists and works in their historical and social context. Instead of pitting composers against each other, we can recognize the similar background and complementary qualities of, say, a Bach and a Telemann. In comparison with Bach, Telemann’s musical persona is warmer, friendlier, more outgoing. Bach seems to elevate hard work as a principle of musical art. Telemann prioritizes enjoyment. In the words of François Filiatraut, “The goal of all [Telemann’s] tireless activity was, by encouraging people to listen to and play music, to bring them together. He was not interested in training specialists. Rather, he targeted competent and discerning amateurs, helping them communicate and converse by means of the art of sound.”

Filiatraut adds: “Bach’s vision was metaphysical, Telemann’s was humanistic.” Telemann’s talents and interests were more wide-ranging than many of his colleagues. A thorough practical musician who could play several instruments (violin, harpsichord, organ, oboe, and several more), he also wrote prose and poetry. Few composers ever penned they story of their lives, but Telemann wrote two autobiographies that are valuable sources of information about musical life in the 18th century. A number of Telemann’s vocal works are set to his own words. He was a pioneer in the field of music publishing, running his own company to print editions of his works and paving the way for the concept of intellectual property rights for music. Telemann’s printed editions spread his music far and wide, overcoming the limitations of hand copied manuscripts. As a composer, Telemann experimented avidly in program (descriptive or storytelling) instrumental music, with delightful pieces based on Don Quixote and Gulliver’s Travels among other subjects.

Telemann was one of the first composers to embrace folk influences; travels in Poland introduced him to fiddling and eastern modalities which he incorporated into his concertos and suites, anticipating musical “nationalism” by at least a century. Telemann advanced the Enlightenment idea of “the mixed taste,” or a happy amalgam of national European styles of music: Italian, French, German, English, and Slavic.

As if all this weren’t enough, Telemann was a force behind the emergence of the public concert, bringing music that was previously reserved for the upper classes to a wider audience. In an age of aristocracy, Telemann was doing his bit to broaden music’s reach, paving the way for Beethoven’s democratic enthusiasm.

This is to say nothing of his sheer output, for Telemann is cited as the most prolific composer in history. I’m not fond of rattling off lists of works, but consider that this composer wrote over a thousand cantatas (like Bach, he was engaged in writing one of these for every Sunday), over 400 orchestral suites, some 35 operas, 46 Passion oratorios, over 100 concertos, and an untold number of chamber pieces of various kinds (sonatas, trios, quartets, quintets). In all Telemann is believed to have written over three thousand compositions—a sizable portion of which are now lost. As for many 18th-century composers, producing music seems to have been for Telemann as natural as breathing.

Telemann wrote for combinations of instruments that no composer had thought of before, and none has attempted since: concertos for recorder and flute; for violin, cello, and trumpet; for two flutes and calchedon (a kind of lute); for violin and three horns. The listing of Telemann’s works in the online Petrucci Music Library has headings like “Works for Political Celebrations” and “Serenades for the Mayor.” Among the composer’s stage pieces is perhaps the only comic opera about the life of Socrates (Der geduldige Sokrates). It might be more apposite to ask what Telemann didn’t do in music; his activities and accomplishments are staggering.

The son of a Lutheran pastor, Telemann at first trained for a career in law. Even in the 18th century music was not always a remunerative or stable occupation, and many families considered it a poor prospect for their children. Telemann achieved musical mastery largely by self-teaching. He built an extremely successful career, spending time in major musical centers like Hamburg, Leipzig, Frankfurt directing operas, writing instrumental music both for courts of nobility and for university student groups, and providing sacred music for the Lutheran churches.

As with any highly productive artist, some of Telemann’s works are more inspired than others, and in the drive to produce great quantities of music he could simply spin notes. But the same may be said even of the greatest masters—of Mozart, Haydn, or Bach. In the 18th century music was usually written to order for specific occasions and purposes, aimed at the here and now. This is epitomized by Telemann’s Musique de Table (Banquet Music) a collection of instrumental pieces originally intended—you guessed correctly—for aristocratic dining. Publishing to some extent allowed music to achieve a more independent and less time-bound existence, and Telemann was a part of this drive too. A good case could be made that Georg Philipp was at the forefront of a number of evolving features of musical life in the modern era.

The 19th century saw a great revival of the works of the great German Baroque composers Bach and Handel. Overshadowed by these two giants, Telemann was reduced to the status of a lightweight, a composer whose music was charming and polished but lacked depth. If you like, he was to Bach as Salieri was to Mozart: competent, but essentially second rate.

When we actually do our homework and listen to the music with open ears, we discover otherwise. Telemann’s works show a higher level of craftsmanship than much of Vivaldi, and his polyphonic approach to composition was not far removed from Bach. Particularly when writing in minor keys, Telemann can approach Bach in poignance and profundity. Yet as a musician, I am grateful occasionally to be able to play something Baroque that is on a less massive scale of complexity than Bach. As a frequent solo Baroque fiddler, I would be lost without Telemann’s wonderful Fantasias for solo violin (he also wrote sets for flute and for viol). Telemann truly knew how to make every instrument speak in its natural accent, one sign of a master composer. Telemann’s concertos are not like any written since: in four movements (alternating slow and fast tempos) instead of the usual three, they are that much more rounded out. They include a luxuriant one for viola, the first ever written for that underappreciated instrument and still a staple of the violist’s repertoire.

There’s an interesting discussion to be had about “depth” in music. François Filiatraut broaches the topic, quoting Michel Tournier in his commentary on Telemann. When we call art “superficial” we mean that it lacks depth of feeling or emotion. But there is something more to the image of superficiality, namely surface coverage. To cover a wide surface is surely an accomplishment, and his varied activities Telemann certainly covered a wider surface than most of his contemporaries. There are some musical genres that Bach never touched (opera is an obvious example), while it’s hard to think of a genre or musical field that Telemann didn’t excel in. That Bach asked Telemann to be the godfather to his son Carl Philipp Emanuel is surely a tribute of his esteem.

Longer-lived than most composers, Telemann was still creating and experimenting in his 80s, ready to welcome the new Classical era represented by Haydn and Mozart. In some ways Telemann was the key composer of the high Baroque era, one who amalgamated all the styles of the day in a style that reflected geniality, civility, and good humor—and at times just plain humor and quirkiness (as witness the Burlesque de Don Quichotte). Perhaps what makes his music so engaging is that it resembles a conversation, a civilized exchange of thoughts—something we could all surely use more of in our world. Walter G. Bergmann for Britannica sums it up nicely: “Profound or witty, serious or light, it never lacked quality or variety.” It’s hard to disagree with that judgment. While Bach may be the pure gold of the Baroque, Telemann is surely fine burnished bronze.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

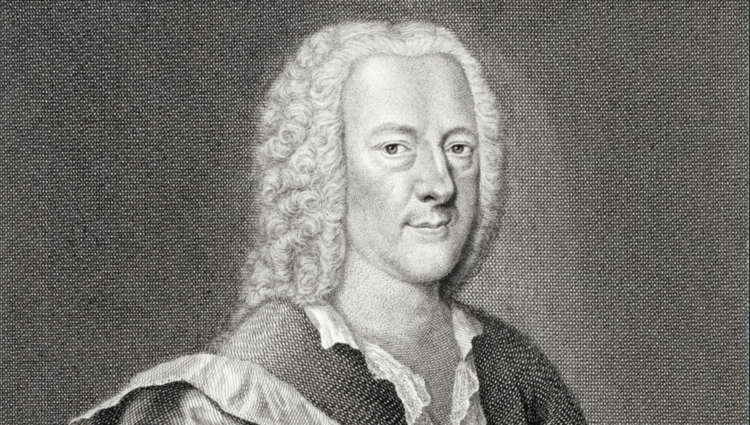

The featured image is a drawing of Georg Philipp Telemann (c. 1745) by Georg Lichtensteger, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.