Ernest Hemingway’s spiritual sensibilities were the foundation of everything he wrote. Indeed, despite his own weaknesses and flaws, his Catholic spirituality infused his writing.

Robert Lazu Kmita:

Dear Ms. Mary Claire Kendall, thank you for agreeing to engage in this dialogue. For our readers, I specify that it relates to your recently launched volume, shortly but significantly titled Hemingway’s Faith (Rowman & Littlefield, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing, December 2024). I will therefore begin with an inevitable question: why Ernest Hemingway? What are the deep reasons—whether personal experiences or readings—that led you to write an extensive monograph about such a troubled, sophisticated, and contradictory writer?

Mary Claire Kendall:

Hemingway came into focus for me on July 2, 2011. That day was the 50th anniversary of his death by his own hand, the newspapers blared. It was not two months after the passing of Gary Cooper, Hemingway’s close friend, whom I had written about since 2008—my first piece finally published on May 13, 2011, 50th anniversary of his death. I was intrigued and started reading The Sun Also Rises, which I had picked up at a book fair some two decades earlier knowing it was a landmark work of literature I must read… at some point…. I was immediately taken in… the writing was so crisp, so gorgeous… so Hemingway….

After soaking in The Sun Also Rises, I finally began delving into Hemingway’s life in earnest on Friday, September 9, 2011, eschewing a Twilight Polo outing with friends, or whatever was on tap that night. Instead I Watched the A&E documentary, Wrestling with Life, with Hemingway whose presence I felt very strongly that night, as if he was saying to me,”It’s my turn.” Three days later, I reached out to Charles Scribner III, whose family publishing house, Charles Scribner’s Sons, had famously published Hemingway, introduced by F. Scott Fitzgerald, and whom I had met five years earlier. He told me Hemingway considered himself a Catholic after being anointed on the battlefield in July 1918, as he lay mortally wounded. That was it. I had my story.

And, yes, without question, he was troubled. But, then most all great artists are. And, I’ve written about many, from the Barrymores to Cooper and Guinness, to name just a few. It’s the wellspring of their art. And, he was oh so sophisticated… (My kind of guy!)… And, yes, contradictory at times… but, on balance, the spiritual through-line of his life and writing is anything but.

Robert Lazu Kmita:

So the beginning of your deep immersion into the world of Hemingway started with The Sun Also Rises. Although it would follow naturally, I will avoid the question in which I would invite you to reveal your preferences regarding his novels. However, I will ask you another question derived from the lesson learned from the personal experience of reading: I believe that the barometer which most surely indicates our deepest preferences is re-reading. So, which of Hemingway’s novels have you re-read most often?

Mary Claire Kendall:

That’s an interesting question. I enjoy re-reading his three collections of short stories—all the stories. But I would highlight in particular “The Battler” from In Our Time; “The Killers” from Men Without Women; and “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” and “The Gambler, The Nun, and The Radio” from Winner Take Nothing. As for the novels by Hemingway that I have re-read, that would be, neck-in-neck in this horse race, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms. Finally, The Old Man and the Sea, a novelette, is another one I re-read. Quite simply, it is a masterpiece of the literary art Hemingway perfected that won him the Pulitzer Prize And shortly after that the Nobel Prize In Literature, awarded, the citation read, “for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style.”

Robert Lazu Kmita:

In the long essay published in 2019 in Saint Austin Review, “Hemingway’s Catholic Heart,” you provided numerous quotes and mentioned characters—such as Don Giuseppi—that reflect the author’s Catholic faith. I am sure that throughout the preparation of your newly released book, you have read and reflected countless times on the presence of this faith in Hemingway’s literary work. What are the most significant episodes from his novels and the characters that can be cited in support of your approach?

Mary Claire Kendall:

The simple answer is, read my book. But I would say, the scene with the priest in A Farewell to Arms where he talks with Frederic Henri about “love” vs. “lust” is particularly poignant, and The Sun Also Rises, so drenched in spirituality juxtaposed with the vacuousness of “the lost generation,” is eye-opening. Also, the love of Mary, as expressed in the aforementioned “The Gambler, The Nun, and The Radio,” is a particular favorite, among so many other scenes from Hemingway’s vast body of work.

Robert Lazu Kmita:

You mentioned in the same article that he considered the apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Fatima as “incontrovertible evidence that the Church was the one true faith.” Could you tell us more about this significant reference? What conclusions did he draw—besides what you have already stated—regarding the significance of the apparition itself and the terrible secrets, including the famous vision of hell?

Mary Claire Kendall:

He did not get into granular detail. Basically, for him it was simple. That Our Lady, the Mediatrix of all grace, appeared on so many occasions, so well documented, starting with her apparition to St. James in Zaragoza, was ipso facto proof that the Catholic faith was the one true faith. That’s it.

Robert Lazu Kmita:

In the penultimate response, you used the phrase “lost generation.” Is there a contradiction between Hemingway’s acceptance of this label and his own religious conversion? Actually, where does the emphasis fall—on Hemingway as “the lost one” or on Hemingway as the Catholic convert? This question is particularly relevant given that the most notable writers of that generation—Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, Edward Cummings, Hart Crane, and others—did not share Hemingway’s Christian faith.

Mary Claire Kendall:

Actually, in writing about “the lost generation,” Hemingway is describing the reality of what he sees among his peers who have just fought “the war to end all wars” and have come back terribly maimed and terribly disillusioned. The passage from Ecclesiastes 1, from which the wording, The Sun Also Rises comes, is very instructive. It’s the reality of human existence—“vanity of vanity, all things are vanity”—which leads the human person to something more permanent, something spiritual—to God—which Hemingway certainly craved in his life, by virtue of his own conversion, which seemingly eluded F. Scott Fitzgerald; albeit if you look closely at The Great Gatsby, in the nihilism, just like in The Sun Also Rises, (and when Hemingway read Gatsby, felt impelled to write this, his first novel), there is a longing for the spiritual.

Robert Lazu Kmita:

Thanking you once again for this interview, I would like to ask you a concluding question that touches on the heart of the matter—that aspiration which inspires the work of conceiving and writing a book. What, then, is the hidden “gift” you wish to offer readers through your book, Hemingway’s Faith?

Mary Claire Kendall:

The gift of faith. The foundation of everything Hemingway wrote, said his sister Sunny, were his spiritual sensibilities. Quite simply, his spirituality—Catholic spirituality—infused his writing. Was he weak and flawed, and did he live large, often too large for his own good? Without question. All the more reason for this critical, largely unexplored dimension that was the key to the man and the writer. A dimension that Hemingway’s Faith illumines.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

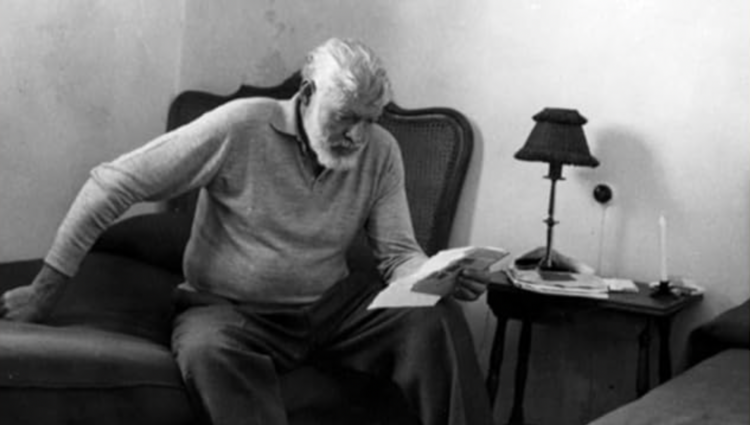

The featured image is Ernest and Mary Hemingway on safari, 1953-54, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.