Now we’ve always been a happiness oriented culture. “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and so forth. Right? But it’s taken a particularly interesting turn: the topic of “meaning” and “meaning in life” is coming to the fore. People, more and more, are talking about not just sheer contentedness, but what it is for a human life to be meaningful. And it turns out that meaning in life is terrifically important. It’s very predictive of well-being. It’s very predictive of how well you are doing in your life in general. So it is no wonder that people are seeking it out. —John Vervaeke, Awakening from the Meaning Crisis

Now we’ve always been a happiness oriented culture. “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and so forth. Right? But it’s taken a particularly interesting turn: the topic of “meaning” and “meaning in life” is coming to the fore. People, more and more, are talking about not just sheer contentedness, but what it is for a human life to be meaningful. And it turns out that meaning in life is terrifically important. It’s very predictive of well-being. It’s very predictive of how well you are doing in your life in general. So it is no wonder that people are seeking it out. —John Vervaeke, Awakening from the Meaning Crisis

To the European, it is a characteristic of the American culture that, again and again, one is commanded and ordered to “be happy.” But happiness cannot be pursued; it must ensue. One must have a reason to “be happy.” Once the reason is found, however, one becomes happy automatically. As we see, a human being is not one in pursuit of happiness but rather in search of a reason to become happy, last but not least, through actualizing the potential meaning inherent and dormant in a given situation…. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it. I want you to listen to what your conscience commands you to do and go on to carry it out to the best of your knowledge. —Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

*

There is a crisis of meaning in the world today. If Viktor Frankl was right, it is because we have been seeking happiness before and more than meaning, the meaning of our own lives and of life itself, and so we are getting neither happiness nor meaning. As I like to say to my humanities students: “Don’t aim for high grades, or even to do excellent work. Aim instead to enjoy the book and the discussions, to discover truth, encounter beauty, and behold goodness, and the grades and excellence will follow.”

Victor Frankl was liberated from Türkheim concentration camp in 1945 after spending two and a half years in four concentration camps. A year later, in nine consecutive days, he wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, both a description of his life in the camps and an articulation of his theory of logotherapy, first developed in 1938, and now further elaborated and deepened in light of his immense suffering, including the death of his father, mother, and brother. The main lesson he learned in the camps was that only those prisoners possessing a firm and deep sense of meaning, transcending worldly considerations and impervious to external circumstances, were able to endure the camps without losing their minds and souls. Frankl came to realize that loss of meaning was the most acute and debilitating form of human suffering, and that the concentration camp was its crucible, with meaninglessness the main torture device. Here in Auschwitz was a microcosm of the “existential vacuum” of the entire contemporary world:

The existential vacuum is a widespread phenomenon of the twentieth century. This is understandable; it may be due to a twofold loss which man has had to undergo since he became a truly human being. At the beginning of human history, man lost some of the basic animal instincts in which an animal’s behavior is embedded and by which it is secured. Such security, like paradise, is closed to man forever; man has to make choices. In addition to this, however, man has suffered another loss in his more recent development inasmuch as the traditions which buttressed his behavior are now rapidly diminishing. No instinct tells him what he has to do, and no tradition tells him what he ought to do; sometimes he does not even know what he wishes to do. Instead, he either wishes to do what other people do (conformism) or he does what other people tell him to do (totalitarianism).

Recently, I taught Man’s Search for Meaning to high school seniors. I am now adding “discovering meaning” to my list of student aims, perhaps to the top of it. Previously, we read and discussed Dostoyevski’s Crime and Punishment; after Frankl, we read Hamlet, a few of Flannery O’Connor’s stories, and Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener. It was amazing to me how well these particular fictional literary texts tied together, and how well Frankl’s gripping account of his harrowing experience in concentration camps and the profound psychological theory he developed in light of it served as an interpretative framework for discussing them. All good stories not only have deep meaning, but are primarily about meaning, and every one of them could have been subtitled Man’s Search for Meaning: Raskolnikov experiments with nihilistic meaninglessness, commits murder, and finds redemption through psychological suffering and the selfless love of a reluctant prostitute; Hamlet’s meaning is revealed to him preternaturally, but he procrastinates—doubts, tests, defers, and defies it—leading to many deaths and much unnecessary suffering until he realizes that “To be or not to be” is not the question, and that “the readiness is all” is ultimately the answer to all questions. Parker and Mrs. Turpin and Hulga find meaning despite their vices through violence and betrayal, but it is not the meaning they wanted nor the messenger they expected to convey it. And Bartleby is the first and perhaps best portrayal—Camus’ Mersault being a close second—of a man with no meaning.

These characters experienced, in one form or another, a vacuum of meaning, and so Frankl provided an illuminating hermeneutical key to unlock the depths of Dostoyevski, Melville, Shakespeare, and O’Connor. But there was even more to Frankl’s book than an illuminating literary lens. It was also a manual for pedagogy, for I came to see that the psychiatric theory and therapeutic practice of logotherapy was akin to the philosophical theory and classroom practice of classical teaching, particularly in the humanities, an illuminating pedagogical lens.

“Ok, students: What is the meaning of the story?” And so begins many a Socratic seminar on a Great Book, literally “searching for meaning.” We want our students to see it, understand it, and ultimately integrate it into their own lives as part of their own search for meaning. But most of all, and here is where Frankl is key, we want them to do this for themselves. Frankl puts it masterfully:

Logotherapy is neither teaching nor preaching. It is as far removed from logical reasoning as it is from moral exhortation. To put it figuratively, the role played by a logotherapist is that of an eye specialist rather than that of a painter. A painter tries to convey to us a picture of the world as he sees it; an ophthalmologist tries to enable us to see the world as it really is. The logotherapist’s role consists of widening and broadening the visual field of the patient so that the whole spectrum of potential meaning becomes conscious and visible to him.

Now, what Frankl means here by teaching is not classical or Socratic teaching, but traditional instruction, by which the propositional knowledge or practical skill possessed by the instructor is transmitted to the pupil through telling or showing. Concerning logotherapy, this is the painter in contrast with whom Frankl proposes the eye specialist. The painter-teacher says, “Here is the world depicted in words as I see it, which is more or less as it really is, for my sight is better than yours and my words are compelling—it would be good for you to see it as I do.” But the ophthalmologist-teacher says, “Let me open this window and brighten the light so you can see what is there, and see what you are called to see.” Here, Frankl is echoing Plato’s understanding of education as conversion, defined by Plato as a periagoge oles tes psyches, or as D.C. Schindler puts it, the “‘art of the turning-around, or conversion [technē … tēs periagōgēs]’, of the whole soul, from the shadows of derivative trivialities to the bright forms of original truth, which shine in the light of the Good, the supreme principle of all things.”

Now, when it comes to meaning, both in psychotherapy and teaching, the painter model just won’t do. As a therapist, Frankl saw meaning as akin to the philosopher’s “supreme principle of all things,” the Good, and the therapist’s role as akin to the philosopher’s, a midwife of intellectual conception and birth as opposed to its father. Indeed, though meaning would seem to be primarily about the truth and not the good, theory rather than practice, metaphysics rather than ethics—“what is the meaning of my life”—it is truly about both, just as the Good is always-already also the True: What is my life for, what good am I to do? Plato certainly experienced the Good/Truth, particularly in the person of Socrates, and he wanted most of all to communicate to others what he experienced so they would experience it for themselves. The Republic was his greatest attempt at this. By Book VII, after about eleven hours of conversation in which Socrates, many times, has alluded to, suggested, spoken of, but never actually defined the Good, Socrates’ interlocutors have become a bit frustrated:

“No, in the name of Zeus, Socrates,” said Glaucon. “You’re not going to withdraw when you are, as it were, at the end. It will satisfy us even if you go through the good just as you went through justice, moderation and the rest.”

“It will quite satisfy me too, my comrade,” I said. “But I fear I’ll not be up to it, and in my eagerness I’ll cut a graceless figure and have to pay the penalty by suffering ridicule. But, you blessed men, let’s leave aside for the time being what the good itself is —for it looks to me as though it’s out of the range of our present thrust to attain the opinions I now hold about it. But I’m willing to tell what looks like a child of the good and most similar to it, if you please, or if not, to let it go.”

Socrates goes on to talk about this “child” of the good, the Sun, but never does get around to providing a precise definition of the Good itself. Why not! Because, like God in Christian theology, Plato knew that the Good is not definable, and not because it is unreal, absurd, or irrational, but because it is too real, suprarational. As Schindler has argued, the Republic itself, in all its dramatic complexity, is the best image of the Good Plato could create, one meant to be experienceddramatically and personally by the reader in the very reading and re-reading of the entire text. It is similar to the Gospels. The person of Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Good, cannot be adequately encountered in a theological definition, or in just one scripture passage taken out of context, but only through the prayerful reading and re-reading of the Gospels, all four of them.

Meaning, like the Good, is also indefinable, for both are tantamount to Reality itself, and reality is something we are not to define but submit ourselves to be defined by. Meaning is nothing but the Real—the True and the Good and the Beautiful as these pertain to me and my life in and through my free subjective, immanent, and particular participation in and surrender to their objectivity, transcendence, and universality. Meaning is thus authoritative, in the classical sense of the term as being not just an arbitrary justification for power, but that which bears witness to and represents the meaningfulness of reality itself, as Schindler puts it: “The ruler bears witness to the meaningfulness of reality, and in doing so he augments its meaning, opening up the world to the dimensions that would allow a properly human existence to unfold.”

But authority is also a justification for the employment of power, but only if in service to that authority, that is, to the Good. The classical teacher, like a ruler, is an authority, and so is empowered to act upon his students, in this case, with the power of his words. But what does he desire to accomplish with his employment of verbal power? Nothing other than enabling the students’ recognition and love of reality, the authority of authority, as it were. Schindler again, “the most fundamental role of authority is not to ‘tell us what to do,’ but effectively to represent the real.” And as meaning is just reality encountered as a calling to significant ethical action in the world, the job of the teacher is to represent meaning to the student by helping the eyes of his soul to see it, in both the Great Texts and the Great Text of Life.

The student sitting in the classroom, like the patient lying on the couch, needs the assistance of an authority figure, surely, but not to be “told what to do.” Truth must be personally discovered and freely loved and obeyed. The logotherapist can use his power to awaken conscience and consciousness, to remove psychological cataracts so that possible meanings are made visible, but his authority ends there. The responsibility to search and find the truth is all on the patient:

Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather he must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible. Thus, logotherapy sees in responsibleness the very essence of human existence.

And the classical teacher can and should use his power to inspire, guide, provoke, question, and model, and like a doctor, repair the intellectual deformities and kill the mind viruses caused by years of habitation in our anti-logos, meaning-averse culture. But most of all, he must bear witness to and represent reality, one that personally beckons to each student to take up the responsibility of both asking the deep questions and attempting to answer them—for himself and for others.

My best class every semester is not the last class before the exam, but the exam itself, a “group oral” in which they discuss together and I observe them. I give them questions and topics to prepare, big-picture, meaning-oriented, synoptic ones that require them to inquire cooperatively and creatively. If I have been a good logotherapist, and they responsible meaning searchers, beautiful new insights and questions emerge in these smaller-group discussions, and it is wonderful to behold. I’ll end here with the topics and questions I assigned them to think about for this semester’s exam I hope they provide a good model for logotherapeutic teaching:

1) Every character in Crime and Punishment contributes something essential to the complex saga of Raskolnikov’s character arc and eventual redemption. Talk about these characters and their role.

2) What led Victor Frankl to believe that discovering and committing oneself to meaning is the purpose of life and the key to overcoming hardship and evil? How does one do this? What does he mean by “meaning”? Is there a crisis of meaning today? What might be the cause of it? How do we overcome it?

3) Can we understand the Tragedy of Hamlet and other stories we read this semester through a Frankleian lens? Consider Hamlet’s transformation from “To be or not to be” (Act III) to “The readiness is all” (Act V). What meaning did Parker discover in and through his Christ tatoo? What does Melville teach us about meaning through the character of Bartleby?

4) What is Flannery O’Connor trying to teach her readers, and how does she do it? How can we learn what she has to teach us?

5) When the narrator interrogates Bartleby as to the reason for his eccentric behavior in refusing to copy any longer, Bartleby replies, “‘Do you not see the reason for yourself’” (interestingly, Melville doesn’t include a question mark). Also this: “What earthly right have you to stay here? do you pay any rent? Do you pay my taxes? Or is this property yours?” He answered nothing.

How might this exchange provide a clue to the meaning of this story?

6) The works we read this semester are all broken stories, but not bent ones. Explain the difference. Have they helped you in your search to discover the meaning of your own story?

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

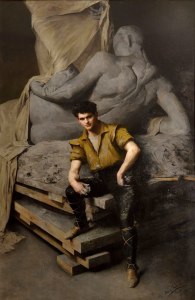

The featured image is “Portrait of Sculptor George Grey Barnard in His Atelier” (1890) by Anna Bilińska, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.