J.R.R. Tolkien is not only the greatest mythmaker of the 20th century, he is our equivalent of Homer, Virgil, and Dante. Just as we read “The Divine Comedy” and come to understand the late Middle Ages, so will someone, five hundred years from now, read Tolkien to understand our era.

I’ve had the opportunity to tell this story before, but it’s very much been on my mind recently. After all, I just read and reviewed three excellent books about Tolkien: Tolkien Philosopher of War for The Independent Review; The War for Middle-earth for National Review; and Tolkien and the Mystery of Literary Creation for Law and Liberty. I thoroughly enjoyed each of them, and each made me think new things about the greatest mythmaker of the 20th century. Given that I’ve been thinking about Tolkien pretty steadily for the past 48 years, it’s not that often that I have new thoughts regarding the man. Yet, each of these books—by, respectively, Graham McAleer, Joe Loconte, and Giuseppe Pezzini—offered some truly fresh insights into the man and the mythology.

I’ve had the opportunity to tell this story before, but it’s very much been on my mind recently. After all, I just read and reviewed three excellent books about Tolkien: Tolkien Philosopher of War for The Independent Review; The War for Middle-earth for National Review; and Tolkien and the Mystery of Literary Creation for Law and Liberty. I thoroughly enjoyed each of them, and each made me think new things about the greatest mythmaker of the 20th century. Given that I’ve been thinking about Tolkien pretty steadily for the past 48 years, it’s not that often that I have new thoughts regarding the man. Yet, each of these books—by, respectively, Graham McAleer, Joe Loconte, and Giuseppe Pezzini—offered some truly fresh insights into the man and the mythology.

Next, I’m diving into a book by Michael Drout, The Tower and the Ruin: J.R.R. Tolkien’s Creation, and I very much expect it to reveal new thoughts as well. I’ll be reviewing that one for The Imaginative Conservative. Furthermore, I’m getting ready to teach a semester-long seminar on The Lord of the Rings for Hillsdale’s English Department. And, to make matters really great, I have a release date on my forthcoming book, Tolkien and the Inklings: Men of the West (Encounter Books). It will be out November 16, 2026. Right now, it looks like the book will be a rather large one at roughly 500 pages. So, my mind is very much on Tolkien.

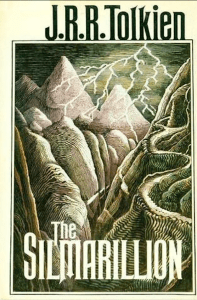

But, back to my story. My oldest brother, Kevin, turned 18 on September 23, 1977. As The Silmarillion had finally come out on September 15, 1977—four full years after Tolkien’s death—my mom bought Kevin a copy for this birthday. I was utterly fascinated by the book, especially by the cover painting, “The Mountain Path,” done by none other than by Tolkien himself. The cover looked at once so menacing and so inviting. I longed to live in that picture. If anything, it reminded me of our many family trips to Colorado and my beloved Rocky Mountains. Yet, that crack of lightning looked so threatening.

But, back to my story. My oldest brother, Kevin, turned 18 on September 23, 1977. As The Silmarillion had finally come out on September 15, 1977—four full years after Tolkien’s death—my mom bought Kevin a copy for this birthday. I was utterly fascinated by the book, especially by the cover painting, “The Mountain Path,” done by none other than by Tolkien himself. The cover looked at once so menacing and so inviting. I longed to live in that picture. If anything, it reminded me of our many family trips to Colorado and my beloved Rocky Mountains. Yet, that crack of lightning looked so threatening.

I loved it, and I “borrowed” the book, probably much to Kevin’s chagrin. I had just turned age 10, and I tried so hard to understand the book. Naturally, I failed, but not without some serious dedication. As it turns out, I read the introductory parts of the book, “The Ainulindalë,” probably close to 10 to 15 times. It’s the creation story in which God (Eru/Iluvatar) sings the universe into existence with the aid of the Valar. Melkor, though, the diabolus, tries to derail the creation and shape it to his own mind, but God stops him. The Valar, who had a part in creating much, then descend into time and become the guardians over creation. Reading that chapter radically shaped my view of Genesis, and, to this day, even though I teach Genesis every fall to Freshman, there’s a very Tolkienian spin on my interpretation of it all.

For whatever reason, I didn’t return to Tolkien until the summer of 1980, aged 12, in which I so proudly saved up my lawnmowing money, rode my bike down to one of our three bookstores in town, and purchased the boxed set of The Hobbit, The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King. To say that I devoured all four that summer would be the understatement of my life. I took every word of the four books into my very soul and being. Those words have never left me. Though I had been reading for several years at that point, nothing hit me like Tolkien did. Never one to do anything half-heartedly, I became obsessed with all things related to the author—his stories, his life, his paintings, his poetry, everything. Somehow, I must’ve also found out that Tolkien was a serious Catholic, so I included him in my nightly prayers. Frankly, this was rather prophetic on the part of my much younger self, as there is now a rather serious movement to have Tolkien canonized. I very much feel that he should be, and I, to this day, often include Tolkien in my litany of saints at the end of the Holy Rosary.

At the same time I read Tolkien, several of my closest friends and I started playing Dungeons and Dragons. It’s a rather complicated game, though we were the perfect age to immerse ourselves in it, loving and niggling over all the myriad complicated rules. For me, D&D was nothing less than an extension of Tolkien’s world. If I wasn’t reading about it, as Dungeon Master, I was extending it and playing in it.

Jump forward to my junior year of college at the University of Notre Dame. That fall, 1988, I took a brilliant course, “Philosophy and Fantasy,” taught by a well-known Platonist, Professor Kenneth Sayre. I immediately loved Sayre and the class, and, for my semester long research paper, I wrote a paper on Tolkien’s Catholicism. Now, in 2025, that’s not unusual at all, and a huge number of books about Tolkien’s faith abound. But, in the Fall of 1988, no one had written on that. I’m very proud to note that the first to publish a book on the subject, Joseph Pearce, was still eleven years from publishing Tolkien: Man and Myth. Much to my surprise, Sayre chose my essay as one of the three best in class, and he had me present it to the class. It was truly one of the great moments of my life, as I had never been so recognized for any academic achievement.

Though I continued my love affair with all thing Tolkien, I really focused my life, 1989-1999, in American history, American Studies, and Latin American studies, as I first earned my M.A. and then my Ph.D. As much as I enjoyed (truly enjoyed) my graduate work and my dissertation, I had dived into so deeply that I could barely see or think straight. When it came time, after successfully defending it, I didn’t have the energy to revise the dissertation for publication. Perhaps to my shame. Still, I wanted so badly to be a professional author and writer. I would walk the aisles of Barnes and Noble dreaming dreams of desire, wanting to be on those shelves some day. I confided all this to my great friend, Winston Elliott (yes, the same Winston who edits this journal). I confided my frustration as well as my wishes. In 1998, being rather direct, he turned to me, looked me straight in the eye, and said, “Ok, Brad. If you could write on any topic, what would it be?” I didn’t even hesitate—on Tolkien and his Catholicism. I wanted to expand my 1988 paper into a book-length study. Winston then challenged me to do so, promising me that he would use every connection he had to find a publisher.

From that moment, inspired by Winston and my newly-wedded wife, Dedra, I jumped right into the deep end, fully immersing myself, yet again, in all things Tolkien. With Winston’s help, I was able to get the attention of Jeff Nelson and Jeremy Beer, and they gloriously published my book in the absolute golden age of ISI Books. It came out in December 2002, just days before Peter Jackson’s The Two Towers hit the movie theaters. While it didn’t compare to the births of my first two children, opening that first box of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth, newly arrived at my house, was truly one of the finest moments in my life. Of course, as I opened that box in the entrance hall of my house, I thought of the direct line of Kevin in 1977 to Sayre in 1988 to Elliott in 1998. What a beautiful and precious journey.

Amazingly, the book sold well. Indeed, it missed being a New York Times bestseller by only a few copies, and, with the exception of the review in Crisis magazine (which was brutal), I received nothing but positive reviews—even one by the Wall Street Journal.

Equally great was being able to introduce Tolkien to my children as well as to several generations of college students at Hillsdale. A labor of love.

Equally great was being able to introduce Tolkien to my children as well as to several generations of college students at Hillsdale. A labor of love.

Twenty-three years after publishing Sanctifying Myth (still in print under a second edition), I’m still reading and devouring Tolkien. Holly Ordway’s Tolkien’s Faith has happily superseded my 2002 book, but I’m still extremely proud of it.

As I’ve had the chance to argue in many places, Tolkien is not only the greatest mythmaker of the 20th century, he is our equivalent of Homer, Virgil, and Dante. Just as we read The Divine Comedy and come to understand the late Middle Ages, so will someone, five hundred years from now, read Tolkien to understand our era.

I’m so very, very honored to have his life tied to mine.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a photograph of the bust of J.R.R. Tolkien in Oxford, Exeter College. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.