The purity of a soul adorned with virtues—this, then, is the deepest motivation behind the discipline, asceticism, and mortifications practiced by the saints of all ages. This purity, which signifies the imitation of the thrice-holy God, represents the very core of Saint Charles’s moral life.

I am convinced that no one who is aware of the depth of the crisis in the Church and the world today doubts that we need models of holiness—that is, models of doctrinal orthodoxy, authentic Christian morality, and perfect charity. Alongside the other two great saints of the Counter-Reformation, Fillipo Neri (1515–1595) and Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), Saint Charles Borromeo (1538–1584) stands as such a model. And yet, we might hesitate.

I am convinced that no one who is aware of the depth of the crisis in the Church and the world today doubts that we need models of holiness—that is, models of doctrinal orthodoxy, authentic Christian morality, and perfect charity. Alongside the other two great saints of the Counter-Reformation, Fillipo Neri (1515–1595) and Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), Saint Charles Borromeo (1538–1584) stands as such a model. And yet, we might hesitate.

First of all, he was an aristocrat. His education and formation have always been accessible only to a very small number of Christians. Moreover, he was the nephew of Pope Pius IV (1499–1565), who granted him the cardinal’s hat in 1560 when he was only 22 years old, and later appointed him Archbishop of Milan in 1564, at the age of 26. Undoubtedly, we are dealing with a leader in every sense of the word—politically and ecclesiastically. And yet, despite his formidable privileges, he knew, like the One who came from the line of King David — our Lord Jesus Christ—how to sacrifice his life for the sheep of his flock.

Thus, the Colossus of Arona became so loved and respected that, as chroniclers tell us, by the 17th century there was hardly a house in Lombardy without a small portrait of the legendary saint. What, concretely, can we imitate? What are those exemplary traits that any Christian can assume in these dark times?

This article will attempt, at least partially, to answer this essential question. Before exploring the key points of a suitable response, however, I will begin by sharing a unique personal experience. Based on it, I might have proposed another title: “In the Footsteps of Saint Charles” or “A Visit to the World of the Borromeo Family.” Perhaps you can tell me which would have been the most fitting title. Why not?

“We are dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants.”

Although this statement appears only in a text written by one of his disciples, the phrase attributed to Bernard of Chartres (12th century A.D.) has gained fame that has overshadowed the rest of his thought. We stand on the shoulders of giants—a symbolic image of remarkable power. It is not only a metaphor for the value and importance of Tradition and continuity but also an expression of understanding based on the mystical and epistemological unity between the great thinkers of the past and those who came after. For accuracy, here is the statement as found in the text of John of Salisbury (1110–1180):

“Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to [puny] dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature.”[i]

Bernard of Chartres used to compare us to [puny] dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. He pointed out that we see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature.

The legacy of this passage—and of the idea attributed to Bernard—can hardly be overstated. The number of authors who have echoed it, from Isaac Newton to Blaise Pascal, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Umberto Eco, and Horia-Roman Patapievici, is difficult to estimate. The learned historian Raymond Klibansky even dedicated a short article to it in the journal Isis.[ii] How could he not? Its profound meaning overflows with significance.

Despite the reflections it has inspired over the centuries—as well as the vehement reactions whose campion was Friedrich Nietzsche—I am absolutely certain that none of its interpreters ever dreamed of the most implausible possibility: its literal fulfillment. In other words, to actually, physically stand upon the shoulders of a giant. Last year, I had the opportunity to discover that such a thing is indeed possible.

Pilgrims in Lombardy

After the sunny days spent in Venice, we set out for Lake Maggiore, passing into a gray, overcast weather that foretold possible rain—the kind that invites melancholy and reflection. I never suspected for a moment that we would have the chance to encounter a true colossus.

When one hears such a phrase, seemingly inspired by Bernard of Chartres, anyone would think it to be nothing more than a metaphor. A visit to the crypt of the famous Milan Cathedral, where the earthly remains of Saint Charles Borromeo rest, would seem to say it all. We spent an extraordinary time contemplating the wonders of the Cathedral. The eternal sleep of the saint prompted us, in reverent silence, to withdraw and continue our journey.

When one hears such a phrase, seemingly inspired by Bernard of Chartres, anyone would think it to be nothing more than a metaphor. A visit to the crypt of the famous Milan Cathedral, where the earthly remains of Saint Charles Borromeo rest, would seem to say it all. We spent an extraordinary time contemplating the wonders of the Cathedral. The eternal sleep of the saint prompted us, in reverent silence, to withdraw and continue our journey.

A small name inscribed on the map guided us toward what had, until then, been unimaginable: Colosso di San Carlo Borromeo. “What could this be?” we wondered. Without much hesitation, we decided to make a detour on our way to the pearl of Lake Maggiore, Stresa, to see what kind of colossus this might be.

The splendor of the lake made us forget the dull weather. Fortunately, the rain was still holding off. Fascinated by the disconcerting diversity of the vegetation, we traveled along the narrow roads, absorbing in every sight that surrounded us. Climbing Via Verbano, we first saw the enormous red building of the so-called Collegio de Filippi. As soon as we turned right, passing in front of the Church of Saint Charles, we were struck with awe: before us, at quite a distance, stood out against the whitish-gray sky the strangely blue statue of the Colossus.

The vastness of the entire plateau does not immediately allow you to grasp the true proportions of the statue. And even less could one imagine—without knowing the history of this remarkable creation—that it is not an achievement of modern engineering. In fact, it is an incredible accomplishment of the 17th century, when the plan of Giovanni Battista Crespi (1573–1632) materialized in the form of this sculpture made of copper. Hence the explanation for its rather unusual color.

The achievement was so highly esteemed that even the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (1834–1904) — the creator of the Statue of Liberty in New York—visited Arona in 1869 to see the magnificent work. Here is his comment, in which one can detect a subtle note of professional envy:

This work of art has a peculiar interest in virtue of its material execution. It is, I think, the first example of the use of répoussé copper mounted on iron trusses. In ancient times metal beaten out into sheets had already been used. But it was used as a covering or was modeled on a solid form of wood or stone. Gold, silver and copper were thus employed in Grecian antiquity and in the extreme Orient. The statue of St. Charles Borromeo is the first known example of a statue of répoussé copper, worked with the hammer inside and outside, and freely supported on iron beams. The work was executed in a somewhat coarse style, but it is interesting, and has the merit of being the result of a bold initiative. The copper is a little thin, measuring only a millimetre in thickness, and yet the whole work has stood until today, that is to say, for two centuries.[iii]

Nearly a century and a half after Bartholdi made that statement, we can now confirm the enduring strength of a work that has stood for more than three centuries on the hills near the city of Arona. However, the greatest surprise came when we discovered, once we reached the statue, that climbing onto the shoulders of the colossus was actually possible. In practical terms, its interior can be ascended all the way up to the area of the shoulders and head, where wide windows open onto breathtaking views of Lake Maggiore and its surroundings.

I cannot describe the emotions I felt when I realized, in the most concrete way possible, that Bernard of Chartres’s metaphor could be fulfilled not just in spirit, but literally. But what meanings might such a wondrous ascent conceal?

On the Shoulders of the Colossus

From the very beginning, I promised you a concrete answer to the question regarding what we can take from a model of holiness such as that offered by Saint Charles Borromeo. His three qualities that any Christian can embrace may be listed right away: the integrity of a perfectly moral life, uncompromising doctrinal rectitude, and the charity that made him a true alter Christus. For each of these three, I have chosen a short passage from his biography.

From the very beginning, I promised you a concrete answer to the question regarding what we can take from a model of holiness such as that offered by Saint Charles Borromeo. His three qualities that any Christian can embrace may be listed right away: the integrity of a perfectly moral life, uncompromising doctrinal rectitude, and the charity that made him a true alter Christus. For each of these three, I have chosen a short passage from his biography.

A fragment from one of his sermons, delivered before candidates for the priesthood, reveals the deepest motives for following the paths of holiness:

If indeed men about to be brought forth into the sight of an earthly king are accustomed to dress in more luxurious clothing so as to shine before their prince with all possible splendor, taking care that nothing should appear out of order or unfitting in their bearing and outward gestures, then how much more concerned must you be, brethren (if you are not utterly thick and stupid, brothers) so as to stand before our most great and high Lord and God with the adornment of the most precious interior virtues of soul.[iv]

If indeed men about to be brought forth into the sight of an earthly king are accustomed to dress in more luxurious clothing so as to shine before their prince with all possible splendor, taking care that nothing should appear out of order or unfitting in their bearing and outward gestures, then how much more concerned must you be, brethren (if you are not utterly thick and stupid, brothers) so as to stand before our most great and high Lord and God with the adornment of the most precious interior virtues of soul.

The purity of a soul adorned with virtues—this, then, is the deepest motivation behind the discipline, asceticism, and mortifications practiced by the saints of all ages. This purity, which signifies the imitation of the thrice-holy God, represents the very core of Saint Charles’s moral life. Every Christian who desires to draw near to the King of the Universe, present on the altars of our churches in the Holy Sacrament, is bound to do everything in their power to fulfill this sacred imperative.

Written by Giovanni Pietro Giussano (1553–1623), the Life of Saint Charles contains true treasures. Cardinal Henry Edward Manning (1808–1892), who wrote the introduction to the English edition of Father Giussano’s biography, has already chosen, on my behalf, two accounts that will allow me to illustrate an exemplary Christian orthodoxy. Here is the first story:

When death stricken with fever, he embarked at Arona to return to Milan to die. In passing over the lake, he examined the boatmen who rowed him, in their knowledge of the faith and of their prayers.[v]

Stricken by a merciless illness, the man who had overseen the creation of the Roman Catechism (1566), with a faint voice, gathered his last remaining strength to make sure that the boatmen knew the true faith and the essential prayers of every good Christian. His love for divine Revelation — the very truth for whose integrity he fought tirelessly against the heresies of the Protestant Reformation — knew no limits. Nothing is more important than the supernatural gift of Faith. Without compromise, he did everything possible to pass on this priceless treasure — the pearl of Heaven — intact to the Christian people, to souls thirsty for Truth.

Finally, another episode, also recounted with admiration by Cardinal Manning, reveals his perfect love for the most unfortunate among the sheep of his flock:

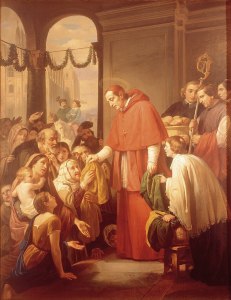

During the pestilence in Milan, he came to a plague-stricken house of which the door was made fast. It was known that a poor mother and her infant were in an upper room. There was no access but by a ladder. St Charles entered through the window, and finding the mother already dead, returned with the infant in his arms, — a deed worthy of a picture.[vi]

Truly, a deed worthy both of a painting and of a giant statue—such as the one that another of his saintly successors, his cousin Cardinal Federico Borromeo (1564–1631), made sure was erected near Arona.

Nothing remains for us, the Christians of today, but to climb upon the shoulders of Saint Charles. We may do so by visiting this marvel of human creativity—but without forgetting what it truly means, in a spiritual sense, to stand upon the shoulders of the Colossus of Lombardy.

Notes:

[i] The Metalogicon of John of Salisbury, A Twelfth-Century Defense of the Verbal and Logical Arts of the Trivium, Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Daniel D. McGarry, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1955, p. 167.

[ii] R. Klibansky, “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants,” Isis, no. 71, XXVI, (December, 1936), pp. 147-149.

[iii] The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World, Described by the Sculptor, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, New York: North American Review, 1890, p. 39.

[iv] Saint Charles Borromeo, Selected Orations, Homilies and Writings, Edited by John R. Cihak, Translated by Ansgar Santogrossi O.S.B., Bloomsbury, 2017, p. 107.

[v] John Peter Giussano, The Life of Saint Charles Borromeo, Cardinal Archbishop of Milan, With Preface by Henry Edward Cardinal Manning, Vol. I, London-New York: Burns and Oates, 1884, p. XXV.

[vi] Ibidem.

__________

This essay originally appeared at the author’s Substack, Kmita’s Library.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Saint Charles Borromeo Handing out Alms to the People” (1853), by José Salomé Pina, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The image of the Sacred Remains of Saint Charles Borromeo in the Crypt beneath the Duomo di Milano come from the author’s archive. The image of Colossus of St. Charles Borromeo, Arona, Province of Novara, Region of Piedmont, Italy, uploaded by Zairon, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.