With his bold pronouncement in the Dred Scott decision that Congress had no jurisdiction over the territories, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney hoped to preempt all political discussion and debate. But he was sadly disappointed, for his majority opinion itself became the focus of a new, and ever more vicious, round of political battles as the presidential election of 1860 approached.

I. The Historical Background

On March 6, 1857, two days after James Buchanan took the oath of office as president of the United States, the Supreme court announced its decision in the case of Dred Scott v. John F.A. San[d]ford.[i]The case was complex and the decision long in coming. In 1834, an army surgeon named John Emerson reported for duty at Rock Island, Illinois.With him was Dred Scott, a slave whom he had recently purchased in St. Louis. Emerson kept Scott with him at Fort Armstrong for two years, despite an Illinois state law forbidding slavery. In 1836, the army posted Dr. Emerson to Fort Snelling, located in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase, in what was then Wisconsin territory and which subsequently became the state of Minnesota. As before, he took his slave Dred Scott with him, although the Missouri Compromise explicitly prohibited slavery north of latitude 36° 30’. While stationed at Fort Snelling, Emerson bought a slave woman named Harriet, who eventually married Dred Scott, although the law did not sanction slave marriages. After several years, the army again transferred Emerson, whose slaves returned with him to Missouri.[ii]

In 1843, John Emerson died. He left his estate, including his slaves, to his wife, and ultimately as a bequest to their daughter. At some time during the years immediately following Emerson’s death, Dred Scott tried unsuccessfully to buy his freedom. Then, on April 6, 1846, Scott or, as is more likely, members of the Blow family to whom he had originally belonged, took drastic action. Scott, or someone acting in his name, brought suit against Dr. Emerson’s widow in the Circuit Court of St. Louis intending to prove that Scott, his wife Harriet, and their two children, Eliza and Lizzie, were free. In his petition to the court, Scott argued that his residence in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory had brought his enslavement to an end.

The precedent on which Scott relied derived from English Common Law, specifically the celebrated case of Somerset v. Stewart (1772).[iii] In Somerset, William Murray, Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King’s Bench, maintained that a slave brought to England could not be compelled to leave and, if coerced to do so, could apply for a writ of habeas corpus and assert his or her freedom. Lord Mansfield declared that slavery was so morally repugnant and so politically odious that it could exist only when the law sanctioned it. In 1827, William Scott, Lord Stowell, presiding justice of the High Court of Admiralty, limited the scope of Somerset. In The Slave, Grace, Lord Stowell determined that a slave, having been brought to England but returning voluntarily to a jurisdiction where slavery was legal, forfeited the right to sue for freedom and remained a slave. Courts in the South, including those in Missouri (but also in Kentucky and Louisiana), consistently rejected Stowell’s ruling in The Slave, Grace and freed slaves who had lived and worked in territories where slavery was illegal. Scott’s lawyers thus had little doubt that he would win his case. They were wrong.

Scott lost his first trial on a technicality. He had brought suit against Dr. Emerson’s widow, Mrs. Irene Emerson, but could produce no witness to swear that Mrs. Emerson owned him and his family. The jury found in Mrs. Emerson’s favor and returned Scott and his family to her custody. It was an absurd decision. The jury, in effect, permitted Mrs. Emerson to keep Scott and his family as slaves because no one could prove that they were, in fact, her slaves.

In 1848, the Missouri Supreme Court granted Scott a retrial. Two continuances, a fire, and a cholera epidemic delayed the case for eighteen months. Not until January 1850 did the case again come before the Circuit Court of St. Louis. Satisfied that Scott had resided in a free state and a free territory, the jury at retrial decided in Scott’s favor. Apparently, he and his family were free. This time Mrs. Emerson did not accept the verdict. She appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court, which, in 1852, reversed the decision of the Circuit Court. The ruling was political. Citing precedent from as early as 1824, the justices admitted that in previous cases Missouri courts had freed slaves who came under the provisions of the emancipating laws of other states or territories. But the justices observed that the courts had acted according to the principle of comity—the courteous acceptance by one state of the laws of another jurisdiction.

The justices were quick to point out that the exercise of comity was optional and not mandatory. To grant or withhold comity was entirely a matter at their discretion. Every state, the justices agreed, retained “the right of determining how far, in the spirit of comity, it will respect the laws of other states.” Candidly acknowledging the rancor that the controversy over slavery was generating throughout the United States, the court decided to exercise its option to withhold the extension of comity that, on other occasions, it had offered. Writing for the court, Judge William Scott explained that:

Times are not now as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made. Since then, not only individuals but States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequence must be the overthrow and destruction of our Government. Under such circumstances, it does not behoove the State of Missouri to show the least countenance to any measure which might gratify this spirit. She is willing to assume her full responsibility for the existence of slavery within her limits, nor does she seek to share or divide it with others. [iv]

By declining to invoke the laws of another state or territory to set Dred Scott free, Justice Scott reversed twenty-eight years of Missouri judicial precedent.

II. Dred Scott’s Appeal

Dred Scott’s only legal recourse was to appeal to the Supreme Court of the Untied States. Meanwhile, sometime in 1849 or 1850, Mrs. Emerson married Dr. Calvin C. Chaffee and moved to Springfield, Massachusetts. She left Scott and his family in St. Louis under the care of her brother, John Sanford, who, although he retained business interests in St. Louis, had also moved east to reside in New York. This complex situation made it possible for Scott’s new lawyer, Roswell M. Field, to initiate a law suit in the circuit court against a new defendant under the diverse citizenship clause of the Constitution. (Art. III, Sec. 2, Para. 1)[v] In 1854, the circuit court granted Scott’s request.

Claiming that he was a citizen of Missouri and that the defendant, John Sanford, was a citizen of New York, Scott sued under the diversity of citizenship formula. Sanford conceded that he resided in, and was a citizen of, New York. He also acknowledged that Scott lived in Missouri, but denied that Scott was a citizen. As such, Sanford asked the court to halt the proceedings and dismiss Scott’s case on the grounds that the court had no jurisdiction to adjudicate it and Scott had no right to bring it. In his plea of abatement, Sanford argued that “Dred Scott, is not a citizen of the State of Missouri, as alleged in his declaration, because he is a negro of African descent; his ancestors were of pure African blood, and were brought into this country and sold as negro slaves.” [vi] Sanford , in essence, affirmed that no black person could be a citizen of Missouri. Even if he were a free man, Scott had no right to sue and the federal court did not have the jurisdiction to hear the case.

The circuit court dismissed Sanford’s plea of abatement and consented to hear the case, but in the end ruled against Scott on the merits. Scott had initiated his suit based on the diversity of citizenship clause. At the same time, he sued Sanford for battery and unlawful imprisonment, requesting $9,000 in damages. Sanford countered that he had not physically harmed Scott. He confessed that he had “gently laid his hands upon” Scott and members of his family, and that he had also “restrained them of their liberty” as the laws of Missouri permitted him to do since Scott was a slave. In May 1854, the case went to trial and, following the decision that the Missouri Supreme Court had issued, the circuit court similarly upheld Scott’s status as a slave. Slavery may have been illegal in the state of Illinois and in the Wisconsin territory, but the Missouri court ruled that neither jurisdiction had ever actually proclaimed Scott and his family to be free. Under such circumstances, they remained in bondage. Scott’s lawyer appealed the decision to the Supreme Court of the United States citing a writ of error. Nearly two years later, in February 1856, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments.

Three questions engaged the justices. First, was Dred Scott a citizen either of a state or of the United States, and thereby entitled to bring suit in federal court? Second, had Scott been freed by his sojourn in Illinois or by his residence in Wisconsin Territory? Third, did Congress have the authority to prohibit slavery in the territories? Nine justices sat on the Supreme Court. They rendered nine different opinions in adjudicating the case of Dred Scott. Seven justices denied Scott’s claim to freedom; two endorsed it.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 1856 was geographically balanced. Five justices hailed from the slave states. They were James Wayne of Georgia, John Catron of Tennessee, Peter V. Daniel of Virginia, John A. Campbell of Alabama, and the Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of Maryland. All five came from slaveholding families, though Justice Wayne no longer owned slaves. The remaining four justices were from the free states: John McLean of Ohio, Robert C. Grier of Pennsylvania, Samuel Nelson of New York, and Benjamin R. Curtis of Massachusetts. Yet, the sectional balance that apparently distinguished the court was misleading. Southern slaveholding presidents had nominated all the justices except Daniel, Curtis, and Campbell. The court was also politically slanted toward the Democratic Party at a time when the southern, proslavery wing was dominant. Only Justice McLean had repudiated his Democratic affiliation and, by 1857, openly associated with the Republicans. Among the justices he alone opposed slavery. Justices Nelson and Grier were “doughfaces,” that is, northern men of southern principles, while Justice Curtis was a conservative aligned with the New England “Cotton Whigs” who, for economic reasons, championed slaveholding interests.

The opinion of the Chief Justice, Roger Taney, became the majority opinion of the court. [vii] Taney had changed from a modestly anti-slavery lawyer to a vehemently proslavery judge. By the time he had became Andrew Jackson’s attorney general in 1831, Taney was adamant in his defense of the right to own slaves and equally unwavering in his opposition to the rights of blacks, slave or free. With the deepening of the sectional crisis during the 1850s, Taney became angry and uncompromising in his support of the South and slavery and, if anything, was even more implacable in his opposition of racial equality than he had been twenty years before. It is not surprising, then, that Taney denied to Scott the benefits of citizenship, among them the right to bring suit in federal court.

In his decision, Taney confirmed that only those persons who had been citizens at the time the Constitution was ratified and their descendants could ever be citizens of the United States. He marshaled considerable evidence to show that blacks had not then been citizens, and thus had no political or constitutional rights. His judgment disregarded those free blacks who, in states such as Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Vermont, did have the right to vote at the time the Constitution was adopted. Taney further contended that native-born blacks could not be made American citizens by a legislative act of the states. They could not, in other words, be naturalized, since that practice was reserved for those born outside the United States. The Constitution, he wrote, “took from the States all power by subsequent legislation” to confer American citizenship on anyone.

Taney formulated a novel, that is, an unprecedented, interpretation of dual citizenship. He concluded that state citizenship did not make an individual a citizen of the United States. The common assumption was that anyone who was a citizen of a state was also a citizen of the United States. Taney demurred:

In discussing this question, we must not confound the rights of citizenship which a State may confer within its own limits, and the rights of citizenship as a member of the Union. It does not by any means follow, because he has all the rights and privileges of a citizen of a State, that he must be a citizen of the United States. He may have all the rights and privileges of the citizen of a State, and yet not be entitled to the rights and privileges of a citizen in any other State.[viii]

Taney rested his judgment entirely on considerations of race. He made it clear that he thought blacks:

are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word “citizens” in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States. On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings, who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.[Blacks were] so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect. [ix]

Jubilant slaveholders immediately understood the significance of Taney’s opinion. Slaves were protected in transit or sojourn. Since Taney had withheld from slaves the right to sue in federal court, their masters could them take them anywhere in the Union and treat them as they pleased without fearing judicial intervention. In his concurrent opinion, Justice Samuel Nelson of New York welcomed an opportunity to adjudicate such cases to establish the precedent that Taney had introduced. He noted that:

A question had been alluded to, on the argument, namely, the right of the master with his slave of transit into or through a free State, on business or commercial pursuits, or in the exercise of a Federal right, or the discharge of a Federal duty, being a citizen of the United States, which is not before us. This question upon different considerations and principles from the one in hand, and turns upon the rights and privileges secured to a common citizen of the republic under the Constitution of the United States. When that question arises, we shall be prepared to decide it.

In the Dred Scott case, Taney and his fellow justices bestowed on slavery greater constitutional protections than any other form of property enjoyed.[x]

Taney’s arguments were at odds with the language of the Constitution, which repeatedly tied national to state citizenship.[xi] The right to vote for representatives to the national legislature, for example, as stated in Article I, Section II, is based on state law and state citizenship.[xii] Article IV, Section I, the full faith and credit clause, required states to grant citizens of other states equal protection and rights under the law, implying that citizenship in one state applied in others and throughout the country.[xiii] But since Taney reasoned that those provisions did not, and were not intended, to pertain to blacks, he ruled that Scott’s stay in Illinois had not released him from bondage. Scott himself was not a citizen. Dr. Emerson never meant his residence in Illinois to be permanent. The laws of Missouri, not those of Illinois,were binding. Scott remained a slave.

Refusing to Scott the rights of citizenship and verifying his legal status as a slave ought to have been sufficient to end the case. Scott lacked the standing to sue in federal court. But neither logic nor precedent guided Taney’s jurisprudence. He went further. Intent to strike down the Missouri Compromise, which Scott’s lawyer had invoked as basis of Scott’s declaration of freedom, Taney disposed of congressional authority to legislate for the territories, beyond providing minimal government during the earliest days of settlement. In turn, the territories had no authority to enact laws inconsistent with, or contrary to, the Constitution. The government of the Wisconsin territory could thus not deprive any citizen of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Doing so violated the Fifth Amendment. To take away a slaveholder’s property merely because he had carried slaves into free territory was unconstitutional. Because slaves were a legal form of property in one part of the Union, Taney assumed, slavery must be legally recognized throughout the Union. [xiv] His was the first judicial attempt to nationalize slavery, as those who opposed slavery, or who sought at least to prevent its expansion, appreciated at the time.

For, in addition to questioning the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise, Taney also eliminated the doctrine of popular sovereignty by prohibiting territorial legislatures to rule on slavery at all. Congress, Taney added, could not delegate to a territorial surrogate a power that Congress did not itself possess. Taney’s argument disclaimed Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution, the so-called Territories Clause, that stated “Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States.” Congress governed the territories. Ignoring historical practice, Taney insisted that the Territories Clause was in force only for those territories that the United States had possessed in 1787:

Whether, therefore, we take the particular clause in question, by itself, or in connection with the other provisions of the Constitution, we think it clear, that it applies only to the particular territory of which we have spoken, and cannot, by any just rule of interpretation, be extended to territory which the new Government might afterwards obtain from a foreign nation. Consequently, the power which Congress may have lawfully exercised in this Territory, while it remained under a Territorial Government, and which may have been sanctioned by judicial decision, can furnish no justification and no argument to support a similar exercise of power over territory afterwards acquired by the Federal Government. [xv]

Taney offered no evidence, cited no judicial opinion, and quoted none of the Founding Fathers to support this fanciful contention. Instead, he merely repeated that the Founders had never contemplated the acquisition of additional territory and so had not extended the Territories Clause beyond 1787. His implication was that a territory acquired afterward, in this instance the Louisiana Territory, lay outside congressional jurisdiction.

III. Consequences & Significance

Not since Marbury v. Madison in 1803 had the Supreme Court employed the principle of judicial review to overturn congressional legislation. The court’s ruling that neither Congress nor the territorial governments could ban slavery, in effect, renounced both the Missouri Compromise and popular sovereignty. Taney had made it clear to Republicans that even should they win control of the national government they could not execute their pledge to keep the territories free of slavery. Slavery could only be proscribed after a territory became a state. By then it might be too well entrenched to remove. It appeared both to the opponents of slavery and to the advocates of free soil that Taney and a majority of the Supreme Court were parties to a vast conspiracy among slaveholders to take over the government.

The decision of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case was not the result of a conspiracy. Most members of the court were inclined to avoid determining the constitutionality of the Missouri Compromise. But President Buchanan had impressed upon them the urgency and necessity of deciding this vexed question once and for all. Buchanan’s pressure may have been improper, but it did not rise to the level of conspiracy or collusion. Yet, most of the justices eventually came to believe that the American people expected them at last to resolve an issue that had bedeviled Congress and divided the Union. Taney was certainly eager to decide the question of slavery in the territories. With his bold pronouncement that Congress had no jurisdiction over the territories, he hoped to preempt all political discussion and debate. He thought that he had fashioned a national ruling that curtailed the free-soil principles of the Republican Party and that, in theory, opened all federal lands to slavery. There ended the debate, or so Taney seems to have anticipated. If he did entertain such possibilities, then Taney, like President Buchanan, was sadly disappointed. For Taney’s majority opinion in the Dred Scott case itself became the focus of a new, and ever more vicious, round of political battles as the presidential election of 1860 approached.

In 1848, Senator John M. Clayton of Delaware had devised an abortive compromise proposal that required the Supreme Court to be the final arbiter of slavery in the territories. Clayton’s idea was to make the issue politically harmless by getting the debate out of Congress and placing it in the courts. Clayton’s compromise bill failed to win support. Nine years later, in 1857, when the Supreme Court did finally rule on slavery in the territories, too much damage had already been done, and the controversial Dred Scott decision only exacerbated an already deteriorating situation.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[i] Sanford’s name was misspelled in court documents as “Sandford.”

[ii] For a history of the case, see Austin Allen, Origins of the Dred Scott Case: Jacksonian Jurisprudence and the Supreme Court, 1837-1857 (Athens GA, 2006) and Paul Finkleman, James Buchanan, Dred Scott, and the Whisper Conspiracy (Gainesville, FL, 2013).

[iii] On the Somerset Case, see Jerome Nadelhaft, “The Somersett Case and Slavery: Myth, Reality, and Repercussions,” 51 Journal of Negro History (July 1966), 193-208 and William M.Wiecek, “Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-American World,” 42 University of Chicago Law Review (Fall 1974), 86-146. On both Somerset and The Slave, Grace, see Paul Finkelman, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity (Chapel Hill, NC, 1981), passim, but especially16-18 and 185-87.

[iv] Scott v. Emerson 15 Missouri 576 (1852). Judge John F. Ryland concurred with Judge Scott’s opinion. Judge Hamilton R. Gamble dissented.

[v] “The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority;–to all cases affecting ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls;–to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;–to all controversies to which the United States shall be a party;–to controversies between two or more States;–between a State and citizens of another State;–between citizens of different States;–between citizens of the same State claiming lands under grants of different States, and between a State, or the citizens thereof, and foreign state, citizens, or subjects.”

The italicized portion of the text is no longer in effect.

Of Scott’s previous lawyers, one had died and the other had left Missouri.

[vi] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 19 Howard (U.S., 1857), 393, 396-97. See also Finkelman, An Imperfect Union, 275 and Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (New York, 1978), 278.

[vii] See Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case, 333-34

[viii] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 19 Howard (U.S., 1857), 405.

[ix] Ibid., 403-404.

[x] For the concluding statement of Justice Nelson’s opinion quoted herein, see Ibid., 468-69. See also Justice Daniel’s concurrent opinion in Ibid., 490.

[xi] See, for example, Justice Curtis’s dissenting opinion in Ibid., 564-633

[xii] “The House of Representatives shall be composed of members chosen every second year by the people of the several States, and the electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State Legislature.”

[xiii] “Full faith and credit shall be given in each State to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other State. And the Congress may by general laws prescribe the manner in which such acts, records, and proceedings shall be proved, and the effect thereof.”

[xiv] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 19 Howard (U.S., 1857), 450.

[xv] Ibid, 442-43.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

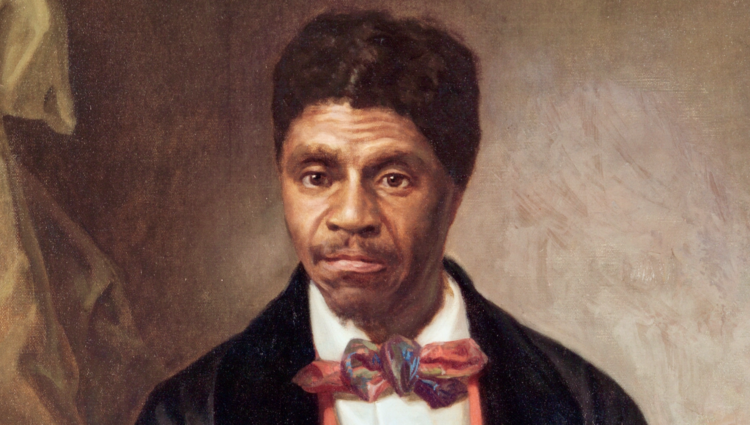

The featured image, uploaded by the Missouri History Museum, is an oil on canvas portrait of Dred Scott (c. 1888) by Louis Schultze, and is used under the MHS Open Access Policy, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.