When he retired from public life in 1817, James Madison turned his full attention to averting a demographic catastrophe. He foresaw a time when a majority of the population would be “without land or other equivalent property and without the means or hope of acquiring it.”

I.

During his presidency, Thomas Jefferson struggled to adapt the social, political, and moral imperatives of classical republicanism to the demands of a modern commercial economy. In essence, Jefferson hoped that Americans could prosper but avoid the perils of luxury, that they could remain industrious without succumbing to greed. He recoiled at the prospect of allowing a primitive, even a barbarous, social order to characterize American life. At the same time, he was also determined to forestall, or at least to postpone, the fall into decadence and corruption that had beset republics in the past as their economies became more complex and sophisticated. Jefferson imagined that in America even the poorest man would long continue to enjoy a measure of economic security and independence. The United States was revolutionary because it had narrowed, if it had not altogether eliminated, the permanent divisions between rich and poor, between privilege and dependence, that characterized the Old World. Such was Jefferson’s utopian dream.

During his presidency, Thomas Jefferson struggled to adapt the social, political, and moral imperatives of classical republicanism to the demands of a modern commercial economy. In essence, Jefferson hoped that Americans could prosper but avoid the perils of luxury, that they could remain industrious without succumbing to greed. He recoiled at the prospect of allowing a primitive, even a barbarous, social order to characterize American life. At the same time, he was also determined to forestall, or at least to postpone, the fall into decadence and corruption that had beset republics in the past as their economies became more complex and sophisticated. Jefferson imagined that in America even the poorest man would long continue to enjoy a measure of economic security and independence. The United States was revolutionary because it had narrowed, if it had not altogether eliminated, the permanent divisions between rich and poor, between privilege and dependence, that characterized the Old World. Such was Jefferson’s utopian dream.

Commerce had been essential to Jefferson’s republican vision from the outset, notwithstanding his persistent fears about the corrupting influence of foreign trade. The profits that commerce generated were the antidote to idleness and degeneracy and, by implication, the stimulus both to industry and the virtue that hard work and property ownership instilled. Beyond the requirements of mere survival, American craftsmen and farmers needed markets, domestic and especially foreign, to absorb the fruits of their labor. Republic virtue, the moral character of the American people itself, depended on the ability to trade. In the absence of markets, Americans had necessarily to confront the unhappy and dangerous prospects of declining into indolence and apathy or resorting to extensive industrial development to keep idle hands employed.

As early as the 1780s, James Madison had speculated that the future crisis of the Republic might originate in its productive capacity rather than in deprivation and want, as Thomas Malthus had proposed in An Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus argued that

the power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man. Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio. A slight acquaintance with numbers will shew the immensity of the first power in comparison with the second. By the laws of our nature which makes food necessary to the life of man, the effects of these two unequal powers must be kept equal. This implies a strong and constantly operating check on population from the difficulty of subsistence. This difficulty must fall somewhere and must necessarily be severely felt by a large portion of mankind. [i]

Madison may have been even more pessimistic than Malthus. Despite intentions to the contrary, Madison posited that the United States would inevitably come to resemble Europe. The best he could do was to suggest ways in which to delay the approaching catastrophe.

As with Jefferson, westward expansion was, or seemed, an integral component of Madison’s solution. The Republic could indefinitely prolong its life and sustain its youthful vitality if it could expand across space rather than develop over time. Of equal and related importance was Madison’s resolve to fashion a commercial republic, well positioned to trade both at home and abroad. The formula was similar to the future that Jefferson envisioned, and just as alluring in its simplicity. If Americans benefitted from continuous and unobstructed access to virgin land and overseas markets, the United States would long remain a nation of small craftsmen and industrious farmers. Farmers could sell their surplus abroad and, in turn, purchase manufactured goods from Europe. Craftsmen could serve the agricultural economy, providing farmers with the other items they needed and thereby preventing an unfavorable balance of trade, while themselves seeking to become landowners. Echoing the analysis of Adam Smith, Madison concluded that this social and economic order corresponded with natural law. Smith had explained that:

According to the natural course of things…the greater part of the capital of every growing society is, first, directed to agriculture, afterwards to manufactures, and last of all to foreign commerce. This order of things is so very natural, that in every society that had any territory, it has always, I believe, been in some degree observed. Some of their lands must have been cultivated before any considerable towns could be established, and some sort of coarse industry of the manufacturing kind must have been carried on in those towns, before they could well think of employing themselves in foreign commerce.[ii]

Blessed with large tracts of arable land, America was uniquely situated to retain its youth and virtue, while simultaneously offering a refuge to the landless poor of Europe and an ample market for the goods that Europeans were compelled of necessity to manufacture.

From Madison’s point of view, the availability of land and the advantages of westward expansion were meaningless if American farmers could not get their surplus to market. Should farmers lack the means of transportation, they would lose all incentive to work or even to migrate in the first place. Inaccessible markets would transform those farmers already living in the west from industrious citizens into indolent rabble, content to live an isolated and brutish existence. A hard scrabble, subsistence economy would prevail, condemning America to endure an unacceptably primitive level of social development. Only “internal improvements,” it seemed,—the construction of roads, canals, and later railroads—could rescue the fringes of settlement from such potentially destructive hazards by integrating all Americans into a single commercial nexus. Commerce, specifically commercial farming and its adjuncts, propelled the advance of civilization.

To sustain itself as an agrarian republic, the United States needed to combine territorial expansion with commercial development. Were Americans denied access either to land or to markets, Madison asserted, the resort to manufacturing would become obligatory. In a letter to Jefferson dated August 1784, he anticipated two possible futures for America:

The vacant land of the United States lying on the waters of the Missispi [sic] is perhaps equal in extent to the land actually settled. If no check be given to emigrations from the latter to the former they will probably keep pace at least with the increase of our people, till the population of both becomes nearly equal. For twenty or twenty five years we shall consequently have as few internal manufacturers in proportion to our numbers as at present and at the end of that period our Imported manufactures will be doubled…. Reverse the case by supposing the use of the Missisipi denied to us and the consequence is that many of our supernumerary hands who in the former case would be husbandmen on the waters of the Missisipi will on the latter supposition be manufacturers on those of the Atlantic and even those who may not be discouraged from seating the vacant lands will be obliged by the want of vent from the produce of the soil and the means of purchasing foreign manufactures to manufacturing in great measure for themselves.[iii]

The occasion for Madison’s remarks was a diplomatic crisis with Spain. Earlier in 1784, the Spanish government, displeased with the boundary settlements contained in the peace treaties that ended the War of Independence, had closed the Mississippi to American vessels and had withdrawn the right to deposit goods at New Orleans.

Like other American statesmen, Madison was frustrated and puzzled by Spanish intransigence. He complained to Jefferson that the Spanish and, by implication, many other European governments, had misunderstood their own economic interests. Free navigation of the Mississippi, Madison pointed out, would defer the emergence of manufacturing in the United States. Were Americans kept gainfully occupied with agriculture, American factories would not appear to compete with foreign, notably English, manufacturing. In addition, American farmers would afford a ready market for European manufactured goods. Madison confirmed that “the settlement of the Western country which will much depend on the free use of the Missisipi will be beneficial to all nations who either directly or indirectly trade with the U.S. By a free expansion of our people the establishment of internal manufactures will not only be long delayed; but the consumption of foreign manufactures long continued increasing; and at the same time all the productions of the American soil required by Europe in return for her manufacturers, will proportionably increase.” [iv] The persistence of such economic and commercial difficulties, on the contrary, would in time initiate a political crisis in the United States that would ultimately thrust the republic into chaos and decline.

II.

It was thus a matter of some urgency for Madison to liberate American commerce from European, and in particular British, restrictions. On March 18, 1786, he wrote again to Jefferson that “most of our political evils may be traced up to our commercial ones, as most of our moral may to our political.”[v] If American merchants could not trade freely the world over, not only the economic welfare of the nation but also the virtue of the people would be in jeopardy. In the almost three decades between the Constitutional Convention and the War of 1812, Madison focused increasingly on the connections between agricultural productivity, access to foreign foreign markets, population growth, and their cumulative effect on the American national character. He was among the first and the few to recognize the disquieting possibility that America might be undone by its success. Rather than the deprivations that Malthus anticipated when the size of the population exceeded the productive capacity of the land, it was the fertility of American soil that far exceeded the requirements subsistence. Such unprecedented natural wealth as the United States possessed might well destroy the inducement to work hard that alone kept Americans not only profitably but also virtuously engaged.

The War of 1812—the Second American War of Independence—over which Madison presided marked a culmination of the effort to craft an international system of free trade and thereby to maintain a virtuous republican citizenry. The debate that raged among Jeffersonians during and after the war centered on the extent to which they needed to acquiesce in Alexander Hamilton’s projection of the American economic future.The exigencies of war and the weight of experience persuaded even Madison to encourage domestic manufactures and internal trade. Yet, Madison continued to fear that Americans were losing the spur to industry. They were squandering their virtue and wasting the bounteous resources with which Providence had blessed the United States.

As a consequence, like other republican thinkers and statesmen, Madison consistently emphasized the relative importance of foreign trade since he believed it did more to excite the vitality of the nation, which would otherwise lay dormant, and to rescue Americans from idleness, poverty, vice, and barbarism. Dr. E. Bollman had put the matter succinctly in 1813, writing that “a nation, when trying to withdraw from the great society of nations, and to suffice to herself, assumes a situation, probably not the most favourable for the attainment of either civilization of prosperity.”[vi] But unlike the countries of Europe, the United States had the capacity to become a world unto itself. Could not domestic markets serve the same purpose as international commerce? Madison, for one, did not think so. In time, the supply of goods would surpass the demand. Domestic markets were limited and would become saturated. As production increased, prices would fall. Many hands would become superfluous as profits diminished, relegated as they would be to unemployment and abandoned to poverty and even to starvation. Overseas commerce was the most certain, and perhaps the only, means to ensure that American farmers and workers could long cultivate the secure and dignified lives necessary to the survival of a virtuous people and a free republic.

Even as Madison entertained such conclusions, he was coming gradually to have second thoughts. The rationale for pursuing foreign trade did not match the reality. Overseas markets had not shown themselves to be as resilient and inexhaustible as Madison initially expected; they, too, had their limits and could become glutted. For that reason, it was also necessary to cultivate domestic markets that would enable Americans more reliably to trade among themselves. A faltering economy undermined the moral integrity of the people. Although few went so far as to eschew foreign trade, many began to wonder whether a measure of economic self-sufficiency might better guarantee the future prosperity and welfare of the republic.

Similar concerns clarify Madison’s attention to domestic manufacturing. Like Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, Madison as president appreciated that economic independence was the bulwark of national security. As he admitted in his Seventh Annual Message to Congress, war with England had revealed the perils of depending on foreign commerce, “ever subject to casual failures for articles necessary for the public defense or connected with the primary wants of individuals.” Prudence demanded that Americans undertake to manufacture at least those items that would facilitate the preservation of independence. The logic of this position led Congress to pass the Tariff of 1816, which Madison and many other Jeffersonian Republicans endorsed. They had not withdrawn their commitment to small-scale and household manufacturing. Instead, they now conceded that it was essential to protect what Madison had identified in his Annual Message as “manufacturing establishments especially of the more complicated kinds,” if only to reduce the vulnerability of the United States in any subsequent war.[vii]

The Jeffersonians remained steadfast in their condemnation of industries that turned out luxury goods while at the same time exploiting and degrading the working class. Americans, after all, had no pressing need for luxuries, whether imported or domestic. But those large-scale manufacturers that produced goods vital to the national defense or affordable consumer goods that enhanced the welfare and comfort of ordinary men and women might not only be tolerated but also nurtured and promoted. By themselves, manufacturers were never responsible for public misery. The real culprits, as in Great Britain, were corrupt politicians and public officials who manipulated unjust laws to the benefit of themselves and their cronies. To cultivate political independence and economic self-sufficiency required other Jeffersonians to join Madison in confronting the unpleasant reality that an agricultural economy might be insufficient to sustain both the industry and virtue of the American people.

Notwithstanding such accommodations, the Jeffersonians yielded to modernity only with reluctance. After the War of 1812, Jefferson himself offered but grudging support to large-scale manufacturing enterprises. He never welcomed any manufacturing with enthusiasm save “the household-handcraft-mill complex of an advanced agricultural society.”[viii] Especially after his acquisition of the Louisiana Territory in 1803, Jefferson placed his faith in westward expansion. He was confident that the vast wilderness would absorb the growing population of the United States so that Americans, as he had written from Paris in 1787, would never have to live “piled upon one another in large cities, as in Europe.” Americans, Jefferson was sure, would “remain virtuous … as long as agriculture is our principal object, which will be the case while there remain vacant lands in any part of America.” For, as he had proclaimed a few years earlier, in 1785:

Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made the peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus in which he keeps alive that sacred fire, which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth. Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example. It is the mark set on those, who not looking up to heaven, to their own soil and industry, as does the husbandman, for their subsistence, depend for it on the casualties and caprice of customers. Dependence begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition.

This “enlargement of territory” would ensure the continued vigor of the republic.[ix]

Challenging Montesquieu’s assertion that republics must be small and comparatively homogeneous, Jefferson insisted the American experience had already confirmed that republics could expand to cover large areas and accommodate a growing population. “A government by representation,” he declared, “is capable of extension over a greater surface of country than one of any other form.”[x] Powerful though it was, Jefferson’s optimism was tempered, and diminished considerably during the last decade of his life. By the time of the Missouri Compromise in 1820, he had grown suspicious that politicians and businessmen from the northern and eastern states were surrendering themselves to greed and corruption. His fears that the future of the republic was at risk had surfaced even earlier. During the War of 1812, for instance, he told Henry Middleton of South Carolina that the agrarian states of the west and south would be the saviors of republican government in the United States. “In proportion as commercial avarice and corruption advance on us from the north and east, the principles of free government are to retire to the agricultural States of the south and west, as their last asylum and bulwark.”[xi] During the 1790s, Jefferson had opposed what he saw as Alexander Hamilton’s conspiracy to subvert the republic. By the 1820s, he was convinced that another anti-republican conspiracy was afoot, and he devoted his the final years to preventing it. [xii]

III.

Directing this anti-republican cabal was John Marshall, the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. According to Jefferson, Marshall intended to effect the “consolidation” of political power so that northern merchants, manufacturers, and politicians could use government to their advantage. Henry Clay’s “American System” was the mechanism introduced to put this scheme in motion. Clay proposed the establishment of a national bank to centralize the control of finance, the imposition of a protective tariff, which would raise consumer prices, to aid domestic manufactures, and the construction of roads, bridges, and canals (“internal improvements”) at federal expense, which would increase the tax burden on ordinary citizens. Clay describe the provisions of the American System as the logical culmination of efforts to secure American economic independence. Jefferson, on the contrary, viewed it as the resurgence of the Hamiltonian principles that he had long despised and contested. [xiii]

The ironies of Jefferson’s interpretation abound. Andrew Jackson did his utmost to prevent the full implementation of the American System, going so far as to dismantle the Second Bank of the United States in 1832, four years before its charter was to expire. In the meantime, the Democrats, Jefferson’s political heirs, implemented an aggressive program of territorial expansion that ended in a war against Mexico during the 1840s. The result of western settlement was at last not the creation of small family farms or the triumph of virtuous yeomen, as Jefferson expected. It was instead rampant land speculation, the development of commercial agricultural, and the spread of slavery, all of which endangered his vision of a pastoral republic.[xiv]

For all of the potential hazards threatening the United States, Jefferson acknowledged that in the distant future the supply of land would also become exhausted. He, like Madison, could not ignore the ominous implications of population growth. The moment of crisis would arrive when society could no longer supply the means or the incentives to labor for that percentage of citizens who had become economically superfluous. Population growth invariably and inevitably led to inequality, corruption, and decline. Even the United States was no exception to the general rule, for, as Malthus had noted, the predicament arose from the “fecundity of the human species” itself.

When he retired from public life in 1817, Madison turned his full attention to understanding and, if possible, to averting, this demographic catastrophe. He feared the natural threat of population growth was far more menacing than the consolidation of political and economic power that had so alarmed Jefferson. Pondering the future course of the republic, Madison foresaw a time when a majority of the population would be “without land or other equivalent property and without the means or hope of acquiring it.” He predicted that the “dependence of an increasing number on the wealth of a few” would engender widespread and unremitting inequality in the United States, with the country divided between “wealthy capitalists” and “indigent labourers.” This “crowded state of property” was not “too remote to claim attention.” Within “a century or a little more,” Madison remarked in 1829, the United States would face the challenge of preserving a republican society and a representative government amid multiplying inequities.[xv] Once vast numbers of Americans lost their economic and political independence, they would also lose their moral judgment and equilibrium. The republic would then enter a new, unprecedented, and perhaps fatal juncture in its history.

For Madison, the present and future welfare of the republic involved more than widespread access to land, the preservation of economic opportunity, and the assurance of political stability. He also contemplated the intractable difficulty of overproduction. America might be undone by its very prosperity and affluence if markets proved inadequate to absorb the agricultural surplus its farmers produced. In 1821, Madison wrote to Richard Rush that Malthus “may have been unguarded in his expressions, and have pushed some of his notions too far.” Malthus’s theories did not apply to conditions in the United States. Specifically, he had assigned to “the increase of human food, an arithmetical ratio.” In a country “as partially cultivated, and as fertile as the U.S.,” Madison countered, “the increase may exceed the geometrical ratio.”[xvi] American soil was too fertile and it may well become impossible year-after-year to find markets in which to dispose of such a bountiful harvest.

Seventeen years earlier, in a letter to the French political economist Jean-Baptiste Say, Jefferson had made much the same point to a different purpose:

The differences of circumstance between this and the old countries of Europe furnish differences of fact whereon to reason, in questions of political economy, and will consequently produce sometimes a difference of result. There, for instance, the quantity of food is fixed, or increasing in a slow and only arithmetical ratio, and the proportion is limited by the same ratio. Supernumerary births consequently add only to your mortality. Here the immense extent of uncultivated and fertile lands enables every one who will labor, to marry young, and to raise a family of any size. Our food, then, may increase geometrically with our laborers, and our births, however multiplied, become effective.[xvii]

But Jefferson never doubted that American farmers would continue to find outlets for their surplus. An agrarian republic would thereby not only serve the interests of its own citizens by enabling them to pursue a virtuous way of life, it would also save the European victims of the Malthusian calculus.

Madison remained dubious. He, too, identified natural tendencies at work in the United States that differed substantially from those Malthus had emphasized. “It is a law of nature, now well understood,” Madison reflected in 1829, “that the earth under a civilized cultivation is capable of yielding subsistence for a large surplus of consumers, beyond those having an immediate interest in the soil: a surplus which must increase with the increasing improvements in agriculture, and the labor-saving arts applied to it.” Under those circumstances, ironically, the sad “lot of humanity” became that “a large proportion is necessarily reduced by competition for employment to wages which afford them the bare necessaries of life.” [xviii] The fate that awaited a large segment of the working poor was not caused by the pressure of population on the availability of land or the inability of the soil to provide adequate sustenance, as Malthus had concluded. It was instead the disappearing sources of employment for persons whose labor had become superfluous in an advanced economy. Madison confronted the dilemma of poverty in the midst of abundance, and wondered whether the republican institutions of the United States had the capacity to hold it at bay.

Madison, of course, trusted that the overseas demand for American produce would continue unabated, indefinitely postponing the crisis that he envisaged by allowing the majority of Americans to remain profitably employed in agriculture. But he could not evade the reality that once markets at home and abroad became saturated, a crisis would ensue and was, in fact, inevitable. Unlike Jefferson, Madison was not sanguine about the prospects of westward expansion, which, he thought, might well hasten the crisis by bringing additional lands under cultivation and increasing the magnitude of the surplus. That possibility was enough to offer a compelling incentive to restrain westward migration. Should the output of American farms surpass the capacity of domestic and foreign markets, the United States would be compelled to develop manufacturing as an alternate source employment even should fertile land remain available.

The tragic consequence would be the emergence of a class society in the United States, with increasing divisions and mounting hostility between rich and poor, just as had occurred in Europe. “Manufactures grow out of the labour not needed for agriculture,” Madison stated in 1833, “and labour will cease to be so needed or employed as its products satisfy and satiate the demands for domestic and foreign markets…. Whatever be the abundance or fertility of the soil, it will not be cultivated when its fruits must perish on hand for want of markets.” When that eventuality came to pass, he added, “the people will be formed into the same great classes here as elsewhere.”[xix] In time, the New World would come to resemble the Old.

Madison’s late reflections on the future of the American republic are sobering. If in a world dominated by free trade, markets were still inadequate, then the possibility that the majority of citizens would remain virtuously employed in agriculture was untenable. Americans would have no choice save to discover or to invent new and different occupations to circumvent the tragedy of inequality and poverty in a nation that could feed the peoples of the world. The irony was as conspicuous as it was painful. To preserve republican virtue, the relentless and unforgiving logic of social and economic development obliged Americans to find new ways to avoid indigence and vice in a society that had prospered beyond all measure.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[i] Thomas Robert Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population, ed. by Anthony Flew (New York, 1979; originally published in 1798), 71.

[ii] Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. by Edwin Cannan (Chicago, 1976; originally published in 1776), Book III, Chapter I, 405.

[iii] James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, August 20, 1784 in The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776-1826, ed. by James Morton Smith (New York, 1995), Volume I, 341. Italics in the original.

[iv] Ibid., 340-41. Italics in the original.

[v] Ibid., 415.

[vi] Dr. E. Bollman, quoted in Emporium of Arts and Sciences II (December 1813), 121.

[vii] James Madison, Seventh Annual Message to Congress (December 5, 1815), in James D. Richardson, ed., Messages and Papers of the Presidents, (New York, 1897), Vol. II, 552.

[viii] Merrill D. Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (New York, 1970), 941.

[ix] Thomas Jefferson to Uriah Forrest, December 31, 1787, National Archives; Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, Query XIX, “Manufactures,” ed. by William Peden (New York, 1954), 164-65; Thomas Jefferson to M. Barre de Marbois, June 14, 1787, in Andrew A. Lipscomb and Albert Bergh, eds., Writings of Jefferson, XV (Washington, D.C., 1903-1904), 131.

[x] Thomas Jefferson to Pierre Samuel Du Pont de Nemours, April 14, 1816, in Dumas Malone, ed., Correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and Pierre Samuel Du Pont de Nemours , 1789-1817 (Boston, 1930), 185.

[xi] Thomas Jefferson to Henry Middleton, January 8, 1813, in Lipscomb and Bergh, eds., Writings of Jefferson, XIII, 203.

[xii] See Robert E. Shallhope, “Thomas Jefferson’s Republicanism and Antebellum Southern Thought,” Journal of Southern History XLII (1976), 529-56.

[xiii] Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation, 992-1004. For a thorough discussion of the substance and politics of The American System, see Merrill D. Peterson, The Great Triumvirate: Webster, Clay, and Calhoun (New York, 1987), 68-84.

[xiv] Jefferson convinced himself that slavery was on the way to extinction in the United States. To hasten its death from natural causes, he adopted the theory of diffusion. If slavery were permitted to expand, its influence would be “diffused,” resulting in the gradual emancipation of the slaves and the eventual disappearance of the plantation system, which, by its nature, was both wasteful and exploitive. See Peterson, Jefferson and the New Nation, 995-1001 and John Chester Miller, The Wolf by the Ears: Thomas Jefferson and Slavery (New York, 1977), especially chapters 23-26.

[xv] Marvin Myers, ed., The Mind of the Founder: Sources of the Political Thought of James Madison (Indianapolis, IN, 1973), 504-505, 518-19.

[xvi] James Madison to Richard Rush, April 21, 1821, in Gaillard Hunt, ed., The Writings of James Madison (New York, 1900-1910) IX, 45-46. Italics in the original.

[xvii] Thomas Jefferson to Jean-Baptiste Say, February 1, 1804, in Lipscomb and Bergh, eds., Writings of Thomas Jefferson XI, 2-3.

[xviii] Myers, ed., Mind of the Founder, 516-17.

[xix] Ibid., 527-28.

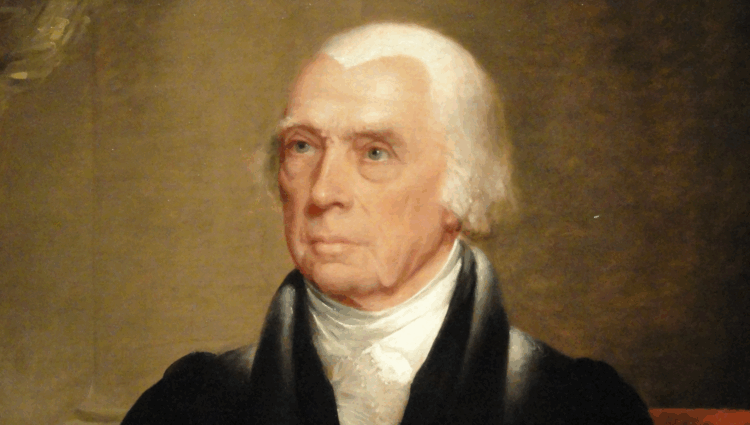

The featured image, uploaded by National Portrait Gallery, Washington, is James Madison by Chester Harding, 1829-1830 (between 1829 and 1830). This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.