The first Christians were urged to pray constantly, and this prayer became known later as the “prayer without ceasing”, “Pray constantly; and for all things give thanks to God, because this is what God expects you to do in Christ Jesus” (1 Thessalonians 17–18). The Morning Off ering and its implementation is the place where the whole of the forthcoming day can be dedicated to loving God through a continual process of prayer, self-sacrifice and the service of others. For the early Christians, this daily endeavour was off ered together with the daily endeavours of all their brothers and sisters at their weekly Mass. What they received together as they offered all the sacrifices made during the previous week, enabled them to receive all the graces that would sustain them spiritually in the forthcoming week. If we only follow their example then our lives will be irrevocably changed, as we exercise our priesthood every day of our lives so that the whole of our lives becomes the Mass, the place where we continually off er ourselves through Christ to the Father. When this profound and mystical spirituality is practised within the mystical body of Christ by all, from the Pope at the top to the humblest lay person at the bott om, then everyone will be always open to the love of the Holy Spirit. ln the early Church when a higher percentage of Christians than at any other time in history were committed to living out this mystical spirituality, their very presence had an enormous influence on the Greco-Roman world in which they lived. The unprecedented example of unbridled selfless charity and all the gifts that charity brings with it converted the ancient pagan world into a Christian world in acomparatively short space of time. The same can be done today. But only the Holy Spirit can do it. It is our privilege to allow him to do it through us, through the quality of our daily prayer life.

The first Christians were urged to pray constantly, and this prayer became known later as the “prayer without ceasing”, “Pray constantly; and for all things give thanks to God, because this is what God expects you to do in Christ Jesus” (1 Thessalonians 17–18). The Morning Off ering and its implementation is the place where the whole of the forthcoming day can be dedicated to loving God through a continual process of prayer, self-sacrifice and the service of others. For the early Christians, this daily endeavour was off ered together with the daily endeavours of all their brothers and sisters at their weekly Mass. What they received together as they offered all the sacrifices made during the previous week, enabled them to receive all the graces that would sustain them spiritually in the forthcoming week. If we only follow their example then our lives will be irrevocably changed, as we exercise our priesthood every day of our lives so that the whole of our lives becomes the Mass, the place where we continually off er ourselves through Christ to the Father. When this profound and mystical spirituality is practised within the mystical body of Christ by all, from the Pope at the top to the humblest lay person at the bott om, then everyone will be always open to the love of the Holy Spirit. ln the early Church when a higher percentage of Christians than at any other time in history were committed to living out this mystical spirituality, their very presence had an enormous influence on the Greco-Roman world in which they lived. The unprecedented example of unbridled selfless charity and all the gifts that charity brings with it converted the ancient pagan world into a Christian world in acomparatively short space of time. The same can be done today. But only the Holy Spirit can do it. It is our privilege to allow him to do it through us, through the quality of our daily prayer life.

If you read the liturgists and the historians of early Christianity who had such an influence on the Second Vatican Council, great emphasis is placed on public liturgical worship. However, this emphasis has often been to the detriment of the personal and daily prayer that enabled the first Christians to participate in the liturgy with such effect. This aspect of early Christian spirituality is regrettably all too often dealt with only as a footnote, or as a brief appendage under the heading of “daily devotions of the early Christians”, or some other such title. It is quite evident that before, during and after the Council otherwise well-meaning scholars, theologians, liturgists and historians have failed to grasp the crucial importance of the personal daily spiritual endeavour of ordinary Christian men and women, most of all in their daily prayer life.

When I was a small boy during the Second World War, I remember the sirens going off shortly after the Mass had begun. The priest simply carried on, nor did the people rush to the shelters despite the sound of bombs dropping all around us. It was the most intense and prayerful Mass I had ever attended. Everybody prayed in those days before, during and after the Mass. The following Sunday our parish priest said that the imminent threat of death enabled us all to experience the Mass as our forebears had experienced it in penal times when at any moment priest and people could be carried off to their death by secret agents of the King or Queen. The same was true for the first Christians when the Mass that we can take so easily for granted could mean imprisonment, torture and death for those who took part in it. But nothing could keep them away from offering themselves with their brothers and sisters in, with and through the One who had given his life for them. However, only Christ can make that offering effective because it is made in, and together with his offering.

In repeating St Peter’s words, “You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a consecrated nation, a people set apart,” our parish priest explained why the early Christians were so aware of their priesthood. They did not just exercise their priesthood at Mass each Sunday, but with the love they received at Mass, they tried to exercise it at every moment of every day of their lives. Then, when they returned the following week, they would offer up all the sacrifices they had made, to receive from God in return, far more than the little they had given. In this way, they would be caught up in an endless cycle of giving and receiving, death and resurrection, that would fit them ever more fully into the mystery of Christ, to receive his love in ever greater measure. St Justin who was born in 100 AD, described what happened at Sunday Mass in his day. After the priest prayed at the end of the great Eucharist prayer, “Through Him, with Him and in Him, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, all glory and honour is yours, almighty Father, for ever and ever,” the Amen of the faithful would all but take the roof off.

St Jerome who was born almost two hundred years later said that in his day this Amen resounded all around the Basilica like a thunderclap. Why? because from earliest times the first Christians exercised their priesthood of self-sacrificial loving which was offered to God, in, with and through Christ himself, in whom they lived and moved and had their very being. It was this priesthood that they celebrated each Sunday when they went to Mass, and the great Amen enabled them to affi rm the very essence of the profound spirituality that bonded them together with Christ, and in, with and through him with the Father. Although I was only young at the time I have never forgotten his words. Nor did I forget what he said to me later when I asked him what Amen meant. The word comes from the Hebrew, and means “I agree”, “let it be so”. The way this Amen all but raised the roof of churches in the early days of Christianity, sums up perhaps more than any other word or action, save martyrdom, the faith of our earliest ancestors and how they joyfully practised it.

The early Christian liturgy was deeply inspiring, vibrant and spiritually re-energising, not because it was correct in every detail, or verbally faultless, but because it depended on the daily personal prayer of the faithful, and the profound mystical spirituality that it generated. It was this that transformed all and everything they said and did into the “prayer without ceasing”. The daily personal spirituality of the first Christians was intense and all-consuming. It contained one vital ingredient on which the whole success of Christianity depended, and still depends. Whether the believers were at prayer, at least intermittently throughout the day, practising regular fasts or serving the poor, they were essentially turning away from self and towards God. In doing this they were practising at all times the repentance that St Peter had called upon everyone to practise on the first Pentecost Day, so they could at all times be open to receive the Holy Spirit. This is what they meant and understood by the “prayer without ceasing” that is to be practised every day of the week and offered at the end of that week, in, with and through Christ to our Father in heaven.

The highest and most profound knowledge of God comes not through knowledge alone, but through love – our love. This happens when through prayer our love is suffused and surcharged by the divine. That is why, when at the end of his life St Thomas Aquinas experienced the love of God with such all-consuming power, he said something astounding. He said that all he wrote before, namely his great Summa Theologica was no more than straw compared with the new knowledge that comes through the love that is wisdom. The consequences of what he said are even more astounding for us personally. Very few of us have intellects like St Thomas Aquinas. Even less have even a fraction of the knowledge contained in his great magnum opus, but if we only learn to open ourselves to receive God’s infinite love that comes to us in prayer, then something dramatic happens. The Holy Spirit will give even the simplest and humblest of us the profound knowledge that is even beyond the grasp of some of the most learned professors of theology.

It is, for this reason, the great mystical theologian and hermit Evagrius Ponticus ( AD 345–399), whose writings summed up the teaching of the Desert Fathers with whom he lived, said, “A person of prayer is a theologian, and a theologian is a person of prayer.” It is in prayer alone that true spiritual wisdom is learnt. In the nineteenth century, crowds flocked not to the great theologians of the day in search of wisdom, but to a simple country priest, the Curé d’Ars. In the same way in the twentieth century, it was to a simple Franciscan Friar, Padre Pio to whom they flocked for the spiritual help they needed, or to Lourdes or Fatima or other places where Our Lady called people to prayer, time and time again. Her message is always the same – “Turn back to prayer”, for it is here that selfless giving is learned that enables our love to be suffused and surcharged by the divine. It is this love alone that can change us permanently into the persons God created us to become from the very beginning. This will enable us “to love and serve him in this life and to be happy with him in the next”, as the catechism used to put it so succinctly.

This essay is chapter nine of The Primacy of Loving and is published here by gracious permission of the author.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

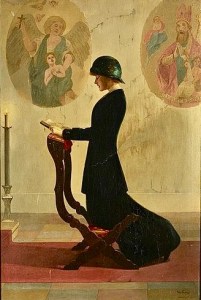

The featured image is “Woman at Prayer” (1912), by Harry Willson Watrous, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.