CENTRAL Bank Digital Currencies are coming, whether we like it or not. What I set out to do here is to explain what they are, examine them in the context of our existing currencies, and ask if we should be afraid of them. There is much hyperbole, so this essay is designed as an introduction looking at both sides of the argument.

It’s sensible to start with a disclaimer on our present currency system. The UK and indeed global central banks have not been much good at preserving either confidence in and or the store of value of their currencies in recent decades. Since the start of the 20th century a degree of price stability which had lasted centuries collapsed.

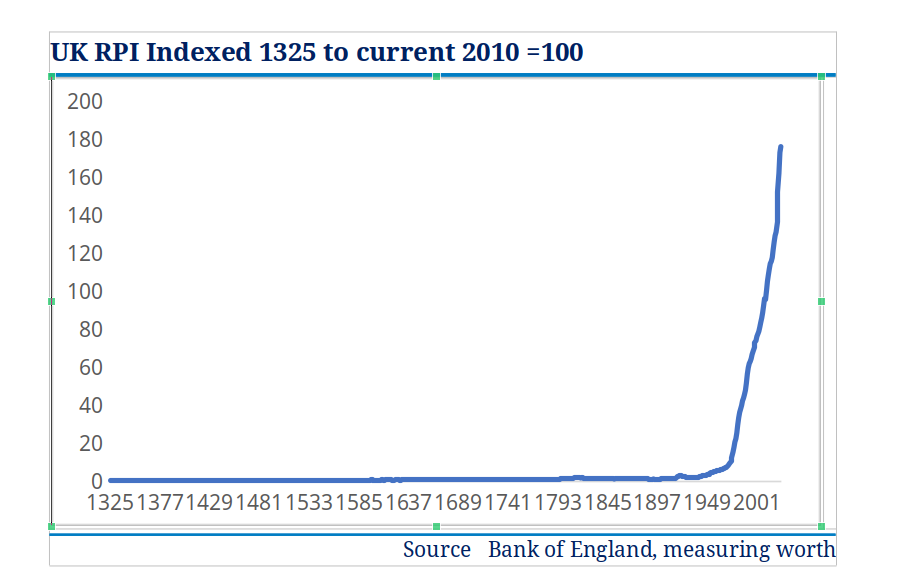

With the obvious caveat that measuring historical inflation is somewhat subjective, we can observe sterling’s performance from the chart above as a store of value over the last 700 years.

In ‘real’ terms, had Medieval Man, born in 1325, come back 400 years later, he might have complained at the price of a flagon of ale. It would have been four times more expensive. Not great for him but recognisable. On the eve of the Great War our Medieval Man would have been reduced to drinking very weak ale as prices had doubled again. So, with the caveats given, over the 589 years between 1325 and 1914 prices increased roughly eightfold. Since the cataclysm of 1914 inflation has eroded the value of sterling a staggering 129 times. Logic would dictate that all things being equal, in a society of untold technological advance, prices should be falling, not rising. This is plainly not the case.

In recent history, sterling been a very poor store of value though relative to most others, USD and Swiss Franc excepted, the UK has been a relative out-performer. The Weimar German mark, Third and Fourth Republic French franc, Argentinian peso, Italian lira and more were all disasters. So when we address the question of CBDC we need to understand that the current situation is not all that great – the combined effect of politicians’ assumption of command over the economy and a currency with no physical tie has proved a recipe for instability. The dying days of traditional fiat currency are not exactly ones of stability. It is in this context that we need to consider this new form of money, CBDC which is moving from the theoretical to the real.

But what exactly is CBDC and how is it different from our historic fiat currency and also crypto currency?

Fiat currency is ultimately backed, in theory at least, by central banks. It is largely commercial banks which create money by lending within their capital structure and regulatory and monetary constraints determined largely by the State. Individual accounts are subsets of this and the ultimate property of the account holder assuming cleared funds, within agreed overdraft limits, which can be used for any legal purpose.

Private digital currency, like Bitcoin, is quite different and is not backed by any central bank. Instead, Bitcoin currency is generated by a competitive decentralised process called mining, with individuals rewarded with new currency if successful in the mining process. Mining is difficult and takes time and resources.

Unlike fiat currency which can be and is created at the whim of the central or commercial bank, Bitcoin is designed in such a way that bitcoins can be created only at a fixed rate which is predictable and decreases over time with the number of new bitcoins being created automatically halving each year until a maximum of 22million are in existence. Bitcoin is in theory at least limited in its quantum – fiat or conventional currency is not and in the latter case has been highly elastic in its issuance.

This elasticity is the great flaw of fiat currencies in terms of preserving the value of money. Thus Bitcoin, so long as there is trust in the process, has a great advantage in its fixed supply. In this sense theoretically it has some of the characteristics of gold clearly without the physical benefits or literally centuries of trust that gold has developed.

Another key difference is Bitcoin uses blockchain databases that are shared across the computer network, providing a secure and decentralised record of transactions. This guarantees fidelity and security and is designed to generate trust without the need of a third party. The traditional central bank or commercial bank is thus redundant in the private crypto world.

Private digital currency is still embryonic and is a speculative asset class. Bitcoin, the market leader by a margin, has a market capitalisation of outstanding ‘coin’ at the time of writing of around $1.7trillion with a long tail of competitors whose combined worth is probably around the same again. This sounds a lot but compared with an approximate $62trillion market cap of the US stock market it remains niche, despite the column inches.

The European Central Bank (ECB) have been investigating the feasibility of CBDC for five and a half years, but ECB President Christine Lagarde has just confirmed that, subject to approval from ‘stakeholders’, they expect to gain clearance to launch a Euro CBDC within a few months. Make no mistake, they will get that legal approval.

While the timeline to proposed legal approval might be shorter than some expected, the direction of travel is not. This is a wakeup call for, like it or not, CBDC is going to happen because (a) elites want it and technology makes it possible and (b) the temptation of elites to proceed is just too great given the potential scope for increased centralised power and observance. Let’s consider these in turn.

Indeed, two countries have operated such a scheme already, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, with very different results. In the latter case the abolition of the near-worthless Zimbabwean dollar for a new gold backed ‘ZiG’ currency has almost certainly been a force for good resulting in an attempt at fiscal discipline from a country ravaged by hyperinflation. Inflation is still high but there are some signs that stability is being restored from a position of extreme dislocation.

In the Nigerian case, the eNaira has not been successful. Nigeria banned private crypto-currency claiming the new CBDC would usher in a ‘new stability’. Unfortunately, the opposite happened with central government control increasing with great volatility and strict limits on daily withdrawals enforced. Worse, while physical cash was still accepted old banknotes became near-worthless, leaving the poorest even worse off.

Clearly Nigeria and Zimbabwe’s characteristics are rather different from advanced Western nations but the warning is clear. If any currency is to succeed, and by success I mean hold a strong store of value, it should be scarce, limited in supply, enjoy very low transaction costs, be widely accepted, unencumbered (i.e. citizens free to use it as they legally see fit without restriction or favour) and critically be trusted. Current fiat currency meets some of these requirements but critically not the scarce and limited in supply with no underlying asset base to support it.

Part Two will appear tomorrow