ANTICIPATING the delayed reforms to the education and welfare systems, our think tanks have been very busy producing reports. The Autism Tribune has already responded to lengthy documents from Policy Exchange and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, and the Institute for Government and the Youth Futures Foundation each put out papers last week.

I’ve read them all and each says more or less the same thing: the provision of support for children with Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) is fiscally unsustainable. Demand is rising too fast. Schools can’t cope. Special schools are not being built fast enough. Local authorities are going bankrupt. Education outcomes are likely to fall. Something must be done!

Released in time for Halloween, the Institute for Government’s report captures this in five frightening graphs.

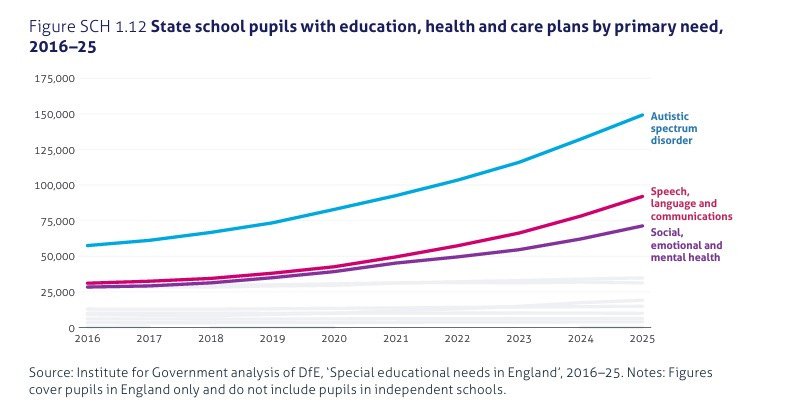

The first shows the rising numbers of children awarded an Education Care and Health Plan (ECHP) in England. Numbers have doubled in less than a decade: from 236,800 in 2016 to 482,600 in 2025 (increasing by 11 per cent in the last year alone). This represents 5.3 per cent (or one in every 20) of all pupils attending state schools in England. Only the most disabled children are granted an ECHP (often after years of delay) and there are another million children with identified Special Educational Needs (SEN) who do not have this extra support (equating to 20 per cent of all students, or one in every five).

It is salient that the proportion of ECHPs awarded for Autistic Spectrum Disorder has risen from a quarter (26 per cent) in 2016 to over a third (34 per cent or 149,200 pupils) in 2025. This indicates that it not ‘softer’ diagnoses that are driving up trends.

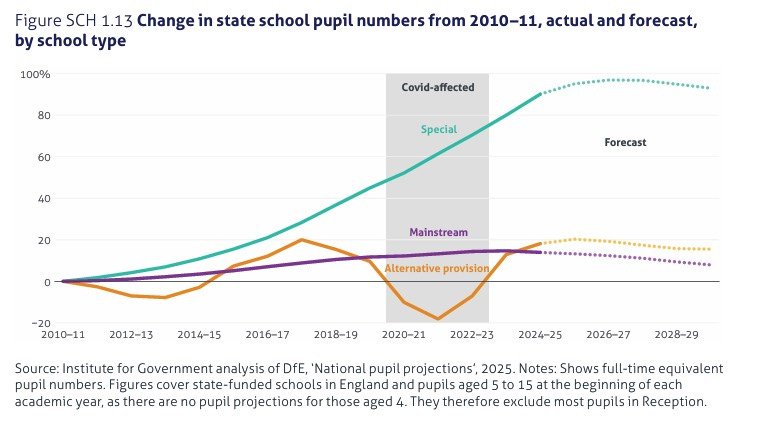

The second scary graph shows pupil allocation by type of school from 2010/11 with forecasts to the end of the decade.

It is hard to believe, but the number of children in special schools has risen by 90 per cent in just 15 years(since 2010/11). Our son was one of the dots on the graph. No parent or local authority opts for this kind of school unless it is the only option on hand. What’s more, it is clear that demand is outstripping supply.

The lack of spaces in state special schools is forcing more children with ECHPs to stay in mainstream provision, as well as increasing pressure on local authorities to pay for more expensive alternatives, and this helps to explain the third remarkable graph.

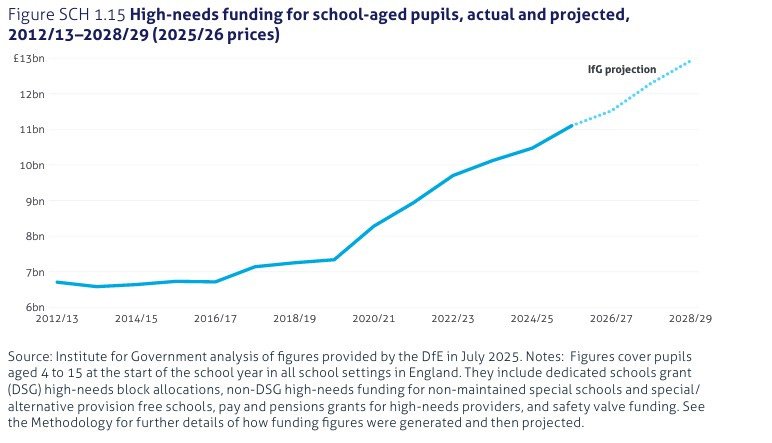

In just over ten years (from 2012/13 to 2025/6) the funding dedicated to what is called ‘high-needs support’ has increased by two-thirds (66 per cent) in real terms, rising from £6.7billion to £11.1billion. This includes special grants given to schools as well as funding for independent provision, and costs are expected to carry on rising to reach £13billion by 2028/9.

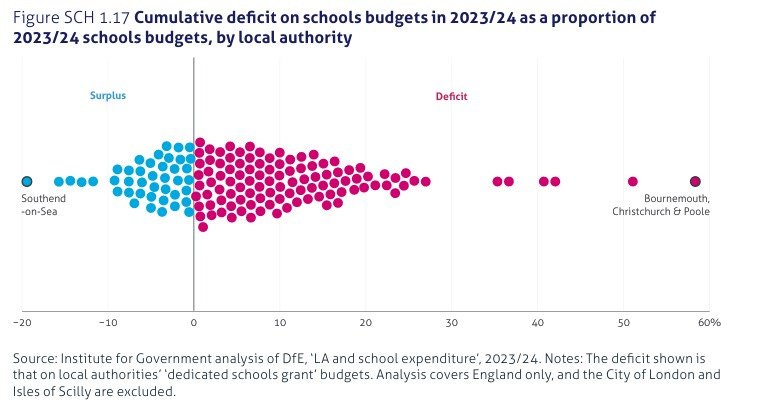

These costs have profound implications for council budgets and services, and it is surprising that less deprived rural areas are found to fare worse than more deprived urban locations. An old funding formula likely penalises apparently wealthier areas in part because autism and related disorders impact across the population regardless of class (unlike most other areas of government spending in the UK).

Graph four shows the extent to which most local authorities are in deficit, the worst being Bournemouth, Chichester and Poole, which recorded a cumulative deficit of £62.5million in 2023/4.

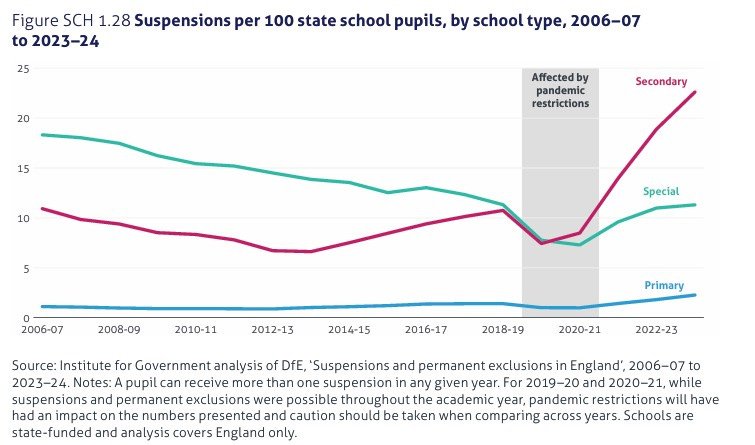

Graph five exposes the scale of pupil suspensions.

There were as many as five suspensions in every state secondary school class on average in just one year (2023/4). Children living in the poorest areas and those with SEND were heavily over-represented in the group of pupils suspended. The same children have the worst attendance record at school.

In sum, the report is extremely alarming.

What’s more, this was reinforced by a Youth Futures Foundation report on the numbers of young people aged 16-24 who are not in any kind of Education, Employment or Training (NEET). Almost one million people belong to this group – including our son. Half of them have a registered disability and a third of this group have autism. We know from experience that they will likely never work. They will need benefits and care for the rest of their lives. Looking at the pipeline in schools, the rates are going to go up.

We have no choice but to address the underlying causes of this problem before it gets any worse. For far too long, the rise in demand has been explained away. We are told it is down to improved awareness, better access to diagnosis and a more inclusive approach.

However, Amber Dellar, the author of the Institute for Government report, does open the door to a more honest approach.

She reports: ‘The pandemic appears to have triggered a global surge in mental health difficulties among children and young people. Similarly, the increase in speech and language needs has been linked to reduced early-life interaction among “lockdown babies”. And long waiting lists for children’s mental health care and cuts to services like children’s centres mean schools are increasingly relied on to provide support.’

Unlike others, she is acknowledging that there is a significant rise in demand. She can see that something is causing it. It is not all about better or over-diagnosis and benefit fraud.

We are getting closer to the fundamental questions that need to be asked:

- How did so many of our precious children get so sick and disabled that they are unable to learn?

- What has gone wrong and what can we do about it?

- How can we reverse the trend before it cripples our entire society?

- Is there anything more important?

This article appeared in the Autism Tribune on November 11, 2025, and is republished by kind permission.