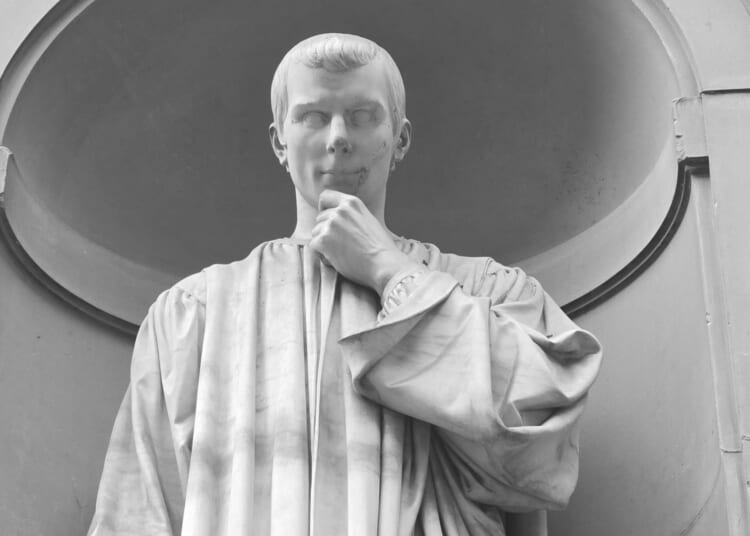

IN 1520, after producing the triad that secured him entry into the halls of posterity – The Prince, Discourses on Livy and The Art of War – Niccolò Machiavelli wrote Life of Castruccio Castracani, an essay nourished by facts of history and creatures of his imagination.

In every sense a son of the Trecento (1281–1328), Castracani provides the raw material with which Machiavelli fashions a relentless Golem striding across the vast fields that make up the fabric of power struggles. Castracani is the manifest incarnation, the inverse sublimation of The Prince. To ensure that the vicissitudes of Castracani’s life fitted the mould provided by the corpus of his celebrated work without strained contortions, Machiavelli drew upon devices used in the classical biographies of Suetonius and Plutarch, two of his masters.

As an introduction to the main character of his reflections, Machiavelli writes: ‘Given the times in which he lived and the city in which he was born, the achievements of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca were outstanding. He sprang from circumstances that were neither favourable nor distinguished, as I intend to show in reflecting on the course of his life. I thought it worthwhile to recall his career to the memory of men, since it seemed to me that I had discovered many things in it, regarding both virtue and Fortune, that are quite exemplary.’

The central purpose of this remarkable brief treatise is to demonstrate that Fortune is not the mother of virtue but rather an ominous power capable of destroying, at the least expected moment, even the most exemplary life. Castracani – nobleman, condottiere (or mercenary) – reaches the summit of power starting from something akin to nothing, thanks to virtù,the capacity to acquire and maintain power, including when necessary by setting ethical constraints aside. He achieves this despite having been educated for service as a modest priest.

The Roman historian Sallust, one of Machiavelli’s inspirations, wrote: ‘Men have no right to complain that they are naturally feeble and short-lived, or that it is chance and not merit that decides their destiny. On the contrary, reflection will show that nothing exceeds or surpasses the powers with which nature has endowed mankind, and that it is rather energy they lack than strength or length of days. If men pursued good things with the same ardour with which they seek what is unedifying and unprofitable, they would control events instead of being controlled by them, and would rise to such heights of greatness and glory that their mortality would put on immortality.’

The simplicity of the style employed by Machiavelli is yet another ornament of the prose, not an attempt at writing without pretence. They say there is no writing without ostentation. Perhaps it would be more accurate to contend that without an aspiration to display, without some degree of affectation, there can be no narrative of any distinction. The mere act of writing is a perfunctory exercise which, in itself, does not involve creation, nor does it generate distinguished narrative processes. Machiavellian brevity – clear, precise, piercing – is a strategy rather than an accident, a means deliberately activated by the author as part of the mechanisms of ostentation.

Machiavelli held a far more pessimistic view of human nature than other humanists of the Quattrocento (roughly the 15th century). Rather than believing that human beings were something just short of angels, as the philosopher Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) asserted, he saw man as a selfish animal, governed by an insatiable desire for material gain and motivated solely by self-interest. An easy prey to appearances, human beings are, he argued, not creatures to be trusted, unless that trust is secured by fear rather than by love.

Paradoxically, this bleak assessment yields optimistic conclusions. If the human condition has been fixed since the Fall, the actions of mankind can be predicted across time. Thus the prudent observer may study them and employ them as a guide for political practice grounded in the facts of history, conceived as a vast didactic reservoir.

Classical political theory tends to delegitimise agitation and violence. Machiavelli had no interest in focusing his attention on ideal or utopian schemes that eliminate – though only in intellectual speculation – social unrest. His work, instead, accepts conflict as a fact of life and claims that, properly channelled and managed, it may become a beneficial and regenerative force.

Curious as it may seem, Machiavelli never pronounced the word politics. That is because his works are not about politics in the classical, Aristotelian meaning of the word, as an activity directed toward discerning the good and shaping a community in which citizens may attain a virtuous and happy life. Aristotle argues that politics is a moral endeavour because its goal is to guide the community (polis) toward virtue and the common advantage.

For Machiavelli, however, Aristotelian politics – real politics – is thoroughly absent. For him, the alpha and omega of so-called political actors is simply to gain and preserve power. Thus, what he discerns in every scuffle in the public arena is what might be called agonocracy:a system whose signature trait is perpetual competition, ferocious rivalry, and leadership constantly contested, rather than consensus for the common good. No wonder Machiavelli is regarded as a pioneer of modern empiricism – an approach grounded in experience and observation – and as a source of inspiration for Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes, among other influential philosophers.

According to Machiavelli, Castracani was kind to his friends, terrible to his enemies, just towards his subjects, and faithless to foreigners. Never when he could win by fraud did he attempt to win by force because, as he used to say, it is victory, not the manner in which it is obtained, which brings glory.