Plato argues that music is a moral law that gives soul to the universe and wings to the mind. And that music gives flight to the imagination, charm to sadness, gaiety to life and is the essence of order and leads to all that is good and just and beautiful. Is Plato right that musical innovation alters the fundamental laws of the State?

It is not everyday that the world arranges itself into a poem.

—Wallace Stevens, from the Adagia

And so I think we should say that the fig wood is more appropriate than the golden unless you have an alternative suggestion…. Which of the two ladles is appropriate to the soup and to the pot? Or is it likely to make the soup smell nicer, and at the same time, my friend, it would not shatter our pot, spill the soup, put out the fire, and deprive the impending diners of their noble meal, while the golden one would do all that.

—Plato, Hippias Major

So we shall have to enlarge the city further… filling it with numerous things which go beyond the strict necessity… for example, the practitioners of mimesis: the many who use shapes and colors, the many who use musical forms, the poets and their assistants (rhapsodes, actors, dancers, theatrical impresarios) and the makers of multiple products, including women’s cosmetics.

—Plato, The Republic

Musical innovation is full of danger to the State, for when modes of music change, the fundamental laws of the State always change with them.

—Plato, The Republic

By Way Of An Introduction

I have an affection for Wallace Stevens, his poems and especially his prose piece The Necessary Angel. It seems to me a consummate of philosophy this lengthy essay on reality and the imagination. His further point? How poetry can breath life into a dull world repossessing reality through the imagination which manifests itself in its domination of words. He doesn’t modify “dull” with”Platonic.” But it’s likely he, Stevens, would argue that art is the most educational “thing” we have and should live in cozy friendship with its rivals, philosophy and theology, or for that matter science.

I have an affection for Wallace Stevens, his poems and especially his prose piece The Necessary Angel. It seems to me a consummate of philosophy this lengthy essay on reality and the imagination. His further point? How poetry can breath life into a dull world repossessing reality through the imagination which manifests itself in its domination of words. He doesn’t modify “dull” with”Platonic.” But it’s likely he, Stevens, would argue that art is the most educational “thing” we have and should live in cozy friendship with its rivals, philosophy and theology, or for that matter science.

He would also argue that the imagination daily wishes to be indulged with real flowers and not those that are paper.

Wouldn’t Plato say the same?

But art tends to stand defenseless, and when and if it succeeds the greatest powers of the mind can be displayed with the most thorough knowledge of human nature. So says Iris Murdoch in her conclusion to her magisterial The Fire and the Sun, where she acknowledges that Plato produced some of the finest remarkable images as well as the most artful dialogue even sometimes with humor. And his battle against sophistry and magic both of which are even to this day unimproved and unrewarding, so to speak.

So, it’s tempting to refute Plato, as Murdoch writes, simply by pointing to the existence of great works of art, and in doing so to describe their genesis and their merits in Platonic terms, noting the while how a transcendental like beauty can become suspicious because of its lapse into charm. Kant, she adds, was prepared to treat beauty as a symbol of the good. So stated, good art can be thought of as a sort of office mate with philosophy and with that a more vibrant understanding of the beauty of life itself.

More on that when I conclude this essay.

The Platonic Epigrams

The second pair of epigrams are snippets from Plato’s Hippias Major and Republic, a pair of wonderful books of philosophy in which Socrates has discussions with Hippias and Glaucon and Adeimantus listing his grievances against the arts, which include women’s cosmetics and gold ladles, but in which he also seems to be proposing a meticulous system of censorship, harsh criticism if not sneers.

And at issue with Hippias, surely one of the earlier dialogues, is that Socrates/Plato is is still young and “trying out” his philosophical method. It’s less assured than later dialogues but fun to read since it bears all the hallmarks of a satirical comedy. So, when questioned by Socrates on “beauty,” Hippias, the sophist, is quick and easy to answer that beauty is a pretty girl. Socrates regards the answer but then advances the argument as to whether beauty is gold.

The issue is to formulate a definition of beauty and locate a place for art in life.

Errors abound.

But Socrates does offer the argument that beauty is that which is appropriate, which is useful, favorable, and a pleasure, although not all pleasures possess beauty.

He’s concerned, as we all know, with social stability and the meddling artists who require independence… but independence can become irresponsible; a contemporary example might be the “anti-mimetic movement.” One can, however, become uneasy with any philosopher who disregards the arts as a spiritual treasury and there’s always the issue of inspiration, which also could be understood as a kind of madness or what comes about late night at some fraternity house drinking party, where inspiration abounds until the keg runs dry and he who taps the keg is sound asleep.

Isn’t it a bit much, on the other hand, when he concerns himself with the most minute discussions on etiquette—soup, for example, better served with a fig wood ladle and not a golden ladle.

No, by Zeus; a better question is whether the soup itself is beautiful. Questioning apart from that is nothing more/nothing less than a thorough-going pestilence.

And how about the pretty girl who made the soup?

It’s censorship, is it not, and would one be remiss in referring to Plato as a Romantic Puritan for whom going “beyond the strict necessity” would be anathema what with a state enforced dominance of philosophy of a certain kind?

But it leads one to wonder whether Plato may have been in some ways proper to be suspicious and whether it is more morally enlightening to use a wooden fig ladle rather than a gold soup ladle.

As for strict necessity which is of course larger than ordinary necessity which would include “stuff” like food, water, shelter, clothing, sunscreen, all of which fundamental law “recognizes” as essentials required for a person’s basic needs.

Which I hasten to add includes education, which is needed for a citizen to thrive in society.

But as to what kind of education, well, surely the kind purveying the fundamental laws or what is called these days “classical,” which is again thought of as a liberal arts education that emphasizes the whole person, moral character, and of course civil virtue, embracing what are known as the “transcendentals”: truth, goodness and beauty, words that are considered to be modes of reality, or universal values, eternal verities that exist beyond time, space, and matter.

You know, “Forms.”

Having noted that, these transcendentals are often described as metaphysical, immaterial, conceptual, spiritual even: truth, that which conforms the mind to reality; goodness, a positive quality or perfection that makes something attractive or valuable; and beauty, what can be perceived through the senses but which allows for reflection of what is timeless and reflecting divine origin.

One should also note that love is a transcendental and Thomist scholars posit at least seven transcendentals.

And here Plato is worth noting because for him education is a “direction” which starts a person on the journey that will become an aid to that person’s future in life informed by fundamental laws, those strict necessities.

Teach children at the beginning to desire the right things which means to give the body and the soul all the beauty and all the perfection of which children are capable. Knowledge without justice, however, is cunning rather than wisdom, and if one neglects a proper education that person will walk lame to the end of life.

The aim should be virtue and discipline for the soul.

And it’s important to note that since these necessities are fundamental to human life they are, or should be, protected by law to ensure that people have access to the necessities.

Who does the ensuring and how the ensuring is done and how that leads to a certain “quality of life” is supposed to be ensured by the guardians, somehow elected and also known as philosopher-kings who make decisions about public policy.

If I remember properly, Socrates calls them “noble puppies.”

Am not sure what breed of puppy but likely labrador, chocolate.

Poetry comes into question especially since Homer and Hesiod created images of the gods as bickering and acting immorally. Given such, the consequence would be that a citizen’s soul would not be composed and dignified but jangled and unsettled. Poets, therefore, deceive citizens since their imitations often portray characters as whining and wailing.

Thus if this is what poets and playwrights “create” and if the effects are so negative, Plato proposes sending them out of his ideal Republic or at least severely censoring what they created since the arts, so thought Plato, were powerful shapers of character.

And so criticism which takes up the quarrel between philosophy and poetry while asserting a state enforced dominance of philosophy brought to us by the dialectical processes of Socrates dubbed, we know, as the Socratic Method.

And why not?

Surely a good “image” of heroes will show them as exalted beings worthy of moral imitation, or mimesis. Furthermore, a proper moral to a story is one decent people respect and strive for but not what we find with the comic poets who mock everything that is good.

So, then, in enlarging the city further, the city will be filled with things which go beyond strict necessity. But doing so will not necessarily make the city better and more just or of greater benefit but more likely than not contribute to the city’s decline since the pleasures of enlargement contribute to unhealthy appetites.

Having mentioned that, what is a matter of strict necessity is the means by which the citizen’s soul will become composed and dignified.

What then if some musical modes go beyond the matter of strict necessity and fail to be temperate which would suggest no value in the relevance of music in education.

Here’s to you Mrs. Robinson and your sultry suburban tryst.

Assume, however, that especially for children instruction can be had that forms harmonies and rhythms from the tendency constantly to pursue musical novelty and thus a danger to the fundamental laws.

What’s implied by Plato is that the human soul is naturally affected by the musical arts since our souls have structural analogies with musical tunings. The soul, in other words, owns an intimate identity with harmonia, which argues for an affinity between music and virtue and, well, beauty.

Is he right, then, Plato that is, about musical innovation?

What does he mean by fundamental laws of the State?

And is it true that those fundamental laws change when modes of music change? Or for that matter modes of the other arts—theater for example.

These are large assertions and concerned with Plato’s equally large assertions when he accuses artists of moral weakness or even baseness. Art and artists thus become censored when they exhibit the lowest and most irrational kind awareness, a state of vague illusion if not delusion.

Music, and again for that matter theater, should encourage stoicism, calmness, and not uncontrolled emotion. If as an audience, Plato suggests, we become infected the results can be cumulative psychological harm.

Whether Silence Has A Sound

The song was recorded in March 1964 and part of a debut album titled Wednesday Morning, 3 A. M.

It’s an unusual title which suggests, for one reason or another, sleeplessness or maybe anxiety.

It has an interesting history what with a remix bringing the song to a Number One hit on Billboard in January 1966. I was in undergraduate college and remember the whispering sounds coming from dormitory rooms where stereo systems were part of the furnishings. Here are some of the lyrical lines:

Hello darkness, my old friend….

In restless dreams I walked alone….

And the people bowed and prayed

To the neon god they made….

And so forth.

So, folk rock.

If Plato, however, is right, the lyrics which make up the song’s innovation contributed in the 1960s to a change in fundamental laws, and by that I don’t mean “statutes.”

Is it possible to argue that the “speaker” in the song is relating a strong sense of existential tiredness, weariness, which is a different kind of ideation and a feeling of being weighed down by the world on one’s mind, soul, and emotions. Perhaps there’s the fatigue of being one’s “self.”

Which leaves me wondering these days as to whether the song and others of a similar kind became an anthem for those 1960s years and whether such music contributed to social instability as if divinely gifted or did it contribute to more than usual college “stoned” parties and immorality of the soul?

Such a question would lead to discussion as to whether existential tiredness leads the incarnate soul to forget its vision and descend to its lowest parts, egoistic, irrational, and, yes, deluded and lest we forget, enlivening base emotions which ought to be left to wither.

Good taste upstaged by trendy showmanship.

Which leaves me also wondering if Plato would or would not banish such an innovation along with Paul and Art, he being hostile to such innovation which bring changes of heart.

Plato/Socrates goes on to argue that music is a moral law which gives soul to the universe and wings to the mind. And then adds that music gives flight to the imagination, charm to sadness, gaiety to life and is the essence of order and leads to all that is good and just and beautiful.

I’m uncertain the kind of music Plato’s Greeks appreciated except that it was single melodies and subject to mathematical laws of harmony. So, there was a “school of sound” that was part of one’s education and owned a substantial relevance for the just city. The fact that Plato placed great importance on the quality of music is in his belief that music can shape one’s character and even change one’s life.

Music could harmonize the soul, or not.

Having said that, well, the obvious question is to imagine Plato, nee´ Socrates listening in the 1960s to Simon and Garfunkel harmonizing “The Sound of Silence,” and, well, noting that the effect is an exposure to some alarming lyrics that might cause him to think he’s losing his soul and thus corrupting. And would he then be willing to argue that the duo is inspiring the young with lawlessness and boldness and all of which is prevalent in a democracy.

My sense is, however, that he would have tolerated Thelonious Monk and now and again a little bit of Art Pepper.

Hypotheticals

Let’s assume for a moment hypothetically that there is, somewhere, a geographical entity simply called “The Republic,” a sovereignty of sorts. As it is there’s a problem in definition which of course constantly recurs in philosophical discussions. To this day there’s vagueness if not confusion regarding the term Republic, which is a public, sensible thing and a form of administration for which there is a system intended to “rule” the public business and bring good order to the public square.

Such a definition has been recorded in dictionaries down through the years but political philosophers ordinarily begin with Plato and the wonderfully vibrant Republic where Plato, and his alter ego Socrates, develop general notions of immutable things, timeless truths, standards of measurement and appraisal, and of course the often confusing ontology of “Forms,” which leads to why a philosopher should rule the Republic as long as the philosopher is a just man whose character aids in ordering the just state.

So what’s the main point?

Briefly, Books II, III, and IV offer the reader Plato’s theory of the cardinal virtues, and the Republic as a form to show how justice comes to be in the soul of an individual. He’s polite, of course, and he offers reasons as to why he holds an attitude toward the arts which is also an argument concerning the old quarrel between philosophy and poetry and who should and who should not be the purveyors of theological and cosmological information: poets or philosophers.

And literary genres do affect societies and societies need reliability lest they descend into baseness and triviality. And we know that Plato pictured human life as a pilgrimage from appearances to reality, from uncritical acceptance of sense experience and conduct to a more sophisticated and morally enlightened understanding.

How this happens is dependent upon mimetic works that do and those that do not stand in a discernible relationship with issues of correctness which does not suggest that Plato endorses some kid of monolithic doctrine. The best art, or at least the power of the best, should penetrate the interior of the soul raising it to an apprehension of the true, the beautiful and thus the good.

When Plato thus surveys art works he does so in a way that is bound up inseparably with their psychological impact on their audiences and how art works have a significant capacity to share the way in which people view and judge the world.

I recall a moment when I was lecturing to an audience and referenced modernism’s anti-mimetic movement and referred to Jackson Polock as an example. An art history major was in the audience and was quick with questions as part of her defense.

So Then: That’s Entertainment

It’s the sort of subject that comes up at cocktail parties and set mostly in a “center of the world,” an absurdist Manhattan apartment where on one wall is a bicycle that seems never to have been taken down and ridden. The apartment owns a sort of communal refrigerator. People wander in and out without knocking and then flop around moping and when speaking, the conversation is banal and replete with personal oddities that challenge the notion of adulthood.

I have read that the sitcom series is regarded as one of the most influential sitcom shows of all time by such as TV Guide. All of this during the 1990s.

The evidence, so again I read, is that we can all relate. Sitcom is short for situation comedy which in television terms means a genre of comedy centered on a fixed set of primary characters who mostly carry on from episode to episode; the key phrase here is “carry on.”

As for comedy, perhaps absurdist existential humor which doesn’t sound like it might be funny unless meaninglessness in life is funny.

I’ve been asked often enough at cocktail parties my favorite episode, but when I say that if offered a choice between Seinfeld and M.A.S.H., I choose the latter, which is about something rather than nothing. Perhaps I’ve grown a bit peevish about “entertainment.”

More on “that’s entertainment” in a bit.

In re-runs now and likely continuing to be re-run and re-run depending upon ratings. Seinfeld, that is, with a total of 180 episodes. If the pilot is subtracted and the concluding episode, well, a big card-like deck of 178 episodes.

Shuffle the deck and deal the episodes lined up. Gather the deck and do it again, and then again. There’s no significant chronological connection among episodes apart from a “muddle.”

In other words, episode 49 has no logical connection with episode 50 largely because the characters who all have a “being” never “become” something other than what they are which suggests no transformation, especially moral transformation.

Interestingly the episodes have been ranked from best to worse, but I’m unsure the criteria by which we watch absurd characters who “fear” the soup nazi, all of which is a commodity we as viewers consume.

Perhaps that’s the point: an entertaining commodity we consume like soup.

More on that in a bit but with a facetious question posed: Would Plato banish Seinfeld from the Republic? If so, would the reason be that the series represents eikasia (illusion), the lowest rung on Plato’s analogy of the divided line and home for the prisoners in Plato’s myth of the cave (Jerry’s apartment), benighted and unenlightened, superficial, nay, post-modern, which as we all know assumes a break with modernism and which argues that it is no longer possible to rely upon previous ways of representing reality.

A research project, then, would looking something like this:

Survey all the episodes and using the analogy of the divided line attempt to discover an episode in which a character transforms from opinion to belief. The more difficult survey would be to find an episode in which a character offers explanations of the intelligible world of first principles which would require a different kind of knowledge, what Socrates calls dianoia.

The issue, of course, is the idea of an audience likely not interested in listening to characters attempting through dialectic to understand the idea of justice which is necessary to live a just life and to organize and govern a just state.

Ah Jerry, ah Kramer, ah George, ah Elaine, just one moment please and serious discussion about how the river is changing and yet eternally unchanging.

They bicker and argue, Jerry and George, as do George’s parents but I have to be careful lest I leave suggestions in my reader’s mind that I’ve been an avid viewer.

And so: what’s interesting, of course, is the final episode where the friends are locked in a prison for standing by and cracking jokes instead of helping a man who was mugged in front of them. The four are presumably reaping what they’ve sowed, episode-upon-episode-upon- episode of social apathy. But why an arrest and jail time?

Well because under the Good Samaritan Law the violation leads to the four friends receiving their comeuppance.

Simply stated, the law was brought into civil being to encourage people to become good Samaritans ready to render help to others with no fear of any kind of repercussion such as liability and negligence claims. The law suggests that each and every one of us has an affirmative duty to assist our fellow man or woman who need help or treatment.

Thus when the negligent four are charged the argument is that they have failed to act as reasonable prudent persons, i.e. a failure to exercise such care as they might experience in the great mass of New York humanity.

One wonders, though, how to enforce such laws unless a year together in jail and no soup.

Here’s how the “Plato Principle” might apply:

The Plato Principle involves the requirement first to surround one’s self with other people who are a positive influence and who will help one morally grow and never to treat other people as objects but as citizens in a republic of dignity.

Lightly surrealistic of course but also an equivalent to existential heart-felt comedies that make us think about existence, and all of which makes me think of the underlying ideas in Sartre’s No Exit or even Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

And So, To Begin A Summary

I suspect that (at the risk of superficiality) ideological dogmatism is greater than ever before, criticism having evolved well-beyond reviewing books with informed judgments, but which leaves us wondering if there is such a thing as a literary text or are all texts to some degree or another literary? In other words, any “thing” that can be “read” becomes, in effect, a “text.”

These days.

Which leaves me fumbling for a moment wondering what Plato might say or would the result be a sort of Ion redux, where Socrates ruminates with Ion about why Homer is incomparably better than other poets and whether there have been many painters good or bad and whether Ion’s praises of Homer are inspiration or art.

Socrates is getting to the point about art and education which he broadens in Republic where we come to those memorable passages in which he states that should a dramatic poet attempt to visit the ideal state he would be denied admission. In the Laws he becomes more meticulous by proposing censorship and close to what we understand as “puritanism.”

To quote a student of mine, “That Socrates sure has a bug in his bonnet!” A text. And a metaphor, unless a gadfly is a bug.

So I labored to make a critical point for that “youngin” by asking, “What possible good are the ‘arts’ unless as an aid to distinguish appearance from reality, patiently to sort order out of disorder. And isn’t it true that our lives should be lived in a manner in which we surrender our personal will to the rhythm of divine thought as in, say, the original commandment which states with no equivocation that we “shalt not make unto [God] any graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.”

Only the “Good” should be spiritually attractive.

But why?

Such a far remove from us these days but the why demands an explanation.

When was the last time any serious academic engaged in discussion with a colleague as to whether poets or philosophers should be the traditional purveyors of theological and cosmological information? It’s as uneasy a question as the debate in English Department meetings as to whether Shakespeare is or is not greater than Mark Twain.

Silly because we all know the answer.

Can Plato’s Argument Be Summarized?

I’m willing to give it a try.

One serious question is to determine why Plato relegated art to the mental level of eikasia, by which he meant the inability to tell if a perception is an image or something else such as a dream or a reflection in a mirror and thus mistaking such images for reality. The purpose was to compare eikasia to pistis which means the mind’s direct grasp of sensible objects; artists on the other hand “create” indirect graspings through their images.

Plato argues just so, and continued his criticism likely because art delights in trivia and an endless series of senseless images much like one would again find in scenes from Jerry’s apartment or the corner cafe. More so, buffoonery and mockery weaken moral discrimination and its sophistry fakes truthfulness. What discourse exists around characters is also fake dialectic. Such television art cherishes its own volubility, itself and not the truth. The consequence is thus confusing for our sense of moral direction and our ability to discern that direction. Characters are not true characters but pseudo-characters possessed only of false self-knowledge and unhealthy egoism. Imagine, then, 180 episodes which offer only impure and indefinite pleasures but without one single moment of catharsis, as well as irreverent caricature of what Plato called the “Forms,” objects of divine vision.

In Laws, Plato describes such a cast of absurdists as “creators of those who cannot know themselves.”

And that pretty much describes Seinfeld.

Mimetic theories, by which we mean those that privilege the relation of the arts to the world and usually in terms of imitation, are, well, centuries old which suggests they may no longer be applicable upon us since it’s been argued we live in a tangled “post-mimetic age.” After all, how accurate can an imitation be to an external reality unless we are passively content with the phrase “true to life” as a critical term? We know, however, that mimesis was the critical term from Plato well into the Renaissance.

But not without controversy although that controversy might be helpful today if we wish to create a Platonic Reformation, which would mean restoring what Socrates would or would not allow and whether it’s even worthwhile to erect external moral standards.

And if one studies the issue carefully, well, Socrates did not banish so much as escort the feller back across the border capable of returning only after penance for his sins. But we also know that was a matter of Socratic politeness but elsewhere he’s less courteous. On scale, his attitude is curious but safe to say his quarrel is concerned with social stability and those who would contribute to instability. In other words if he thought something trivial he would peck the thing to death—without hesitation.

And we know there’s a bit of jealousy at play because for eons “poets” were prophets and sages and teachers of men especially theological and cosmological wisdom. All is well and fine until Heraclitus attacks Hesiod which sets up a rivalry as to who is the proper authority.

If that’s the case I’m on fair ground objecting to Seinfeld on the grounds of its irrationality.

Let us turn, then, however, to something that has little to do with reality and more a cultural appetite for popular entertainment. Here’s cultural historian and journalist Neal Gabler on this argument: The rise of popular entertainment in the mid 19th century was a deliberate and self-conscious attempt to raze the elitist high culture and their authority by crating a culture the elitist’s would detest. [*]

He might be on to something here by suggesting that with more and more leisure time and as a form of empowerment Americans found entertainment to be the means of enjoying a more pure form of pleasure which may have become in time mindless fun, mere palatable pleasure which became for Americans irresistible.

And the weapons for this cultural revolution? Movies and then television which challenged the movies and now, more likely than not, digital technology and evolutionary exercise for our thumbs.

That’s Entertainment, Too….

The movie featured a superb cast: Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Judy Garland, Donald O’Connor, Debbie Reynolds, Liza Minnelli, Frank Sinatra, and even Buddy Ebsen as well as a multitude of others.

There’s no narrative or story arc, per se, excerpt for the anthem-like title taken from the song of the same name, “That’s Entertainment” dating to a 1953 musical The Bandwagon and with apologies to he late Tony Bennett for his “Steppin’ Out”….

Here’s a sampling:

Everything that happens in life

Can happen in a show

You can make ‘em laugh

You can make ‘em cry

Anything

Anything, anything can go…

****

The clown with his pants falling down

Or the dance that’s a dream of romance

Or the scene where the villain is mean

That’s entertainment!

The plot and the hot simply teeming with sex

A gay divorcee who is after her ex

It could be Oedipus Rex

The world is a stage

The stage is a world of entertainment.

And so forth

What’s it about?

It’s about everything since it’s a compilation film, which means prior films edited together to make a new movie: compiled, in other words from older footage to make up the majority of the principle material. It could be considered a sort of film anthology, an homage of sorts, which led to That’s Entertainment Part II and That’s Entertainment Part III.

Whatever… the whole is a traipse down movie memory lane.

Years ago, when I took a film appreciation class, the point was to survey film history solely with the idea of entertainment as a sort of activity and solely designed to hold the attention or interest of a viewer and giving pleasure if not delight. One might give some thought to how the Oxford English Dictionary defines the word by first offering the word’s etymological French origins which means to engage, to keep occupied, to gain the attention of, to hold the thoughts of a person for a period of time.

Engage, occupy, gain the attention, hold the thoughts, and so on….

Which leaves one to ask the question as to whether entertainment and its industry is or is not mere consumption and designed “to hold the thoughts.”

A big question especially in this age of digital media which daily offers numerous menus from which to consume entertainment and “to hold the thoughts.”

Or is it something more. Is there such a thing as a standard of taste?

And if one were to drift back into time and history can we find the means to decide what is universally good and what is universally bad?

Universally… and a recipe for legitimate criticism, unbiased and seeing the thing for what it really is.

Which bring us again to question whether there is a difference between art and entertainment, the former a matter of insight and moral transformation and is further a political matter which has traditionally been understood as having a role to play in the political community as a common good, its well-being. And if we enlarged upon this idea by suggesting that without this purpose the political community cannot know or understand itself.

And by political community I mean “polis” which of course draws Plato out of the magician’s hat other than a rabbit.

But let me turn to something completely different at the end here….

And Now For Something Completely Different

Plato seems so remote to us these days and surely there will be those who will argue that his conjectures are unreasonable and are far removed from our modern experience.

True.

Few, I know these days, assume that his argument for the “Forms” are intelligible or that his complex mythical images are a means for us to conform ourselves to divine causes. Do we even spend time observing the beauty of the world as the structural work of a divine architect and which suggests in turn that Plato’s philosophy vectors quite nicely into theology? Moral reform, after all, is religious. Having said that one could conclude that Plato’s objections to art are on point when art discounts spirituality and trivializes through endless series of images now coming through my kitchen television fundamentally jumbled.

Good art provides for the spirit and allows us to think on these things, things that are honest, things that are pure, and therapy for the soul. Bad art is a lie about things that are honest and things that are pure. Good art can also subject mankind to a relentless judgment and by judging determining the fate of the soul.

And here is something different:

In his own reflections on the human condition, Wallace Stevens took recourse to theatrical characters which allowed him to introduce comic masks into some of his poems. It’s a confrontation with numerous complications especially the tradition of sad clowns.

But why?

Well, for one, the lines in the poems become the lines of a soliloquy and the speaker an actor who concentrates all his energy into an increased resonance for the spoken lines.

What does that do?

It stirs the imagination deeply only because the mind is most profoundly open, the mask transformative well as revelatory.

Without becoming silly, then, a question could be asked as to whether Plato would banish an artist like Stevens from the Republic?

Here my answer would be, “I hope not!”

What we have is a mind and a body but whom one might call a child of God and one whose jugglery is antidote to disillusion.

The term “God’s fools,” however, would doubtless not refer to Seinfeld characters for whom there is no wisdom in their foolishness.

For Stevens his clowns possess in their hearts wisdom in their foolishness.

The clown’s name is Crispin, the comedian as the letter C, and “As such, the Socrates / Of snails, musician of pears, principium….

And….

….washed away by magnitude. / The whole of life that still remained in him / Dwindled to one sound strumming in his ear. /

Ubiquitous concussion, slap ands sigh….

And who comes to understand the essence of art, the essence of his poetry, and makes a plea for its value apart from aestheticism and who at the end becomes a realist.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

[*] For more on this, consult Gabler’s 1988 An Empire of Their Own.

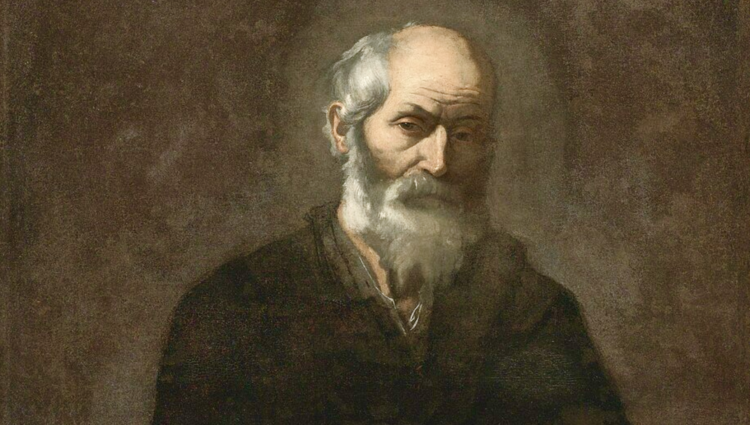

The featured image is “Plato” (c. 1630) by Jusepe de Ribera, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.