While Notes from the Sticks is having a short break, we are repeating some previous columns. This was first published on December 4, 2022.

WHEN we lived in the London suburbs, I would occasionally see clumps of mistletoe in trees, but it doesn’t often grow as far north as Lancashire. It is hard to see in the summer when the trees’ leaves are present but quite easy to spot in winter.

Here is a typical clump:

And everyone knows what it looks like close up:

There are many species of mistletoe round the world but just one is native to Britain, Viscum album. It is semi-parasitic which means that it grows into its host tree (commonly apple, lime and poplar, but it has been recorded in Europe on 200 species) via a structure called a haustorium and extracts nutrients and water, but it also has chlorophyll in its leaves so it carries out a certain amount of photosynthesis on its own. It doesn’t do the host tree any good, though, and can weaken or kill it.

(I looked it up on the Woodland Trust website and it goes on and on about mistletoe’s value as food and shelter for wildlife with only one less than enthusiastic sentence: ‘Trees with large infestations of mistletoe can be negatively affected.’ The Woodland Trust also extols the virtues of ivy, which at the very least can make trees more likely to be downed by strong winds. Strange for an outfit with the stated mission of protecting trees.)

Mistletoe is spread by birds (appropriately, often mistle thrushes) which eat the berries (warning: they are highly poisonous to us, as are the leaves and stems). The seeds inside are coated in a sticky substance which the bird may wipe off its beak on a branch. If a seed catches on the branch the sticky matter hardens and glues it to the bark where it may germinate. If the seed passes all the way through the bird, the same process happens with its droppings.

Which is not particularly romantic, so why is mistletoe associated with stolen kisses at Christmas? I found this story on an American website called The Old Farmer’s Almanac and I fully acknowledge the use of it.

‘In an old Norse legend, Frigga, the goddess of love, had a son named Balder who was the god of innocence and light. To protect him, Frigga demanded that all creatures – and even inanimate objects – swear an oath not to harm him, but she forgot to include mistletoe. Loki, god of evil and destruction, learned of this and made an arrow from a sprig of mistletoe. He then tricked Hoth, Balder’s blind brother, into shooting the mistletoe arrow and guided it to kill Balder. The death of Balder meant the death of sunlight, explaining the long winter nights in the north.

‘Frigga’s tears fell on to the mistletoe and turned into white berries. She decreed that it should never cause harm again but should promote love and peace instead. From then on, anyone standing under mistletoe would get a kiss. Even mortal enemies meeting under mistletoe by accident had to put their weapons aside and exchange a kiss of peace, declaring a truce for the day.

‘By the 1700s, traditional “kissing balls” made of boxwood, holly, and mistletoe were hung in windows and doorways during the holiday season. A young lady caught under the mistletoe could not refuse to give a kiss. This was supposed to increase her chances of marriage, since a girl who wasn’t kissed could still be single next Christmas. According to ancient custom, after each kiss, one berry is removed until they are all gone.’

In case anyone asks, I can’t discover why mistletoe grows in Scandinavia and not in the north of Britain, but I did try.

December 2023: When this column was first published, commenter Arnold Grutt wrote:

‘In case anyone asks, I can’t discover why mistletoe grows in Scandinavia and not in the north of Britain, but I did try.

‘The median temperature line of 60 degrees F in June goes across Great Britain about halfway up but turns abruptly up the North Sea to include the whole of Scandinavia (according to an old book by Karel Voous, a Dutch ornithologist, a pictorial Guide to the Birds of Europe, strangely not listed on Wikipedia.). In short they have warmer summers than the north part of Britain.

‘The distribution of some summer-visitor birds to the UK seems also to be affected by this temperature restriction, e.g. historically, the nightingale but also possibly the marsh tit, an all-year-round resident species. Perhaps mistletoe is limited by the same universal constraint.’

Many thanks, Mr Grutt.

***

This single crab apple has been hanging on to its tree weeks and months after all the other fruit has dropped or shrivelled. I wonder what is different about it?

***

Sheep of the Week goes abroad

Reader Fran Killian sent me these pictures of sheep she and her husband Mike came across in the Salgados nature reserve in the Algarve, Portugal.

They are Algarve Churro (sometimes spelled Churra), a breed derived from the Andalusian Churro which were imported in the late nineteenth century from the neighbouring region of Spain. They are raised mainly for meat, but the wool is used for carpets and stuffing mattresses. In fact the word ‘churro’ means ‘coarse wool’ in Portuguese.

They are large, with distinctive horizontal spiral horns, bigger in the rams than the ewes. About 10 per cent are black or brown.

Like so many older breeds, numbers of the Algarve Churro have been decreasing with the introduction of more productive breeds. There were more than 23,000 in 1996, but now there are around 2,000.

Here is a video of a flock on the move, with two sheep taking the opportunity to have a quick squabble.

Here the breed is pictured on a Portuguese stamp.

Wheels of the Week

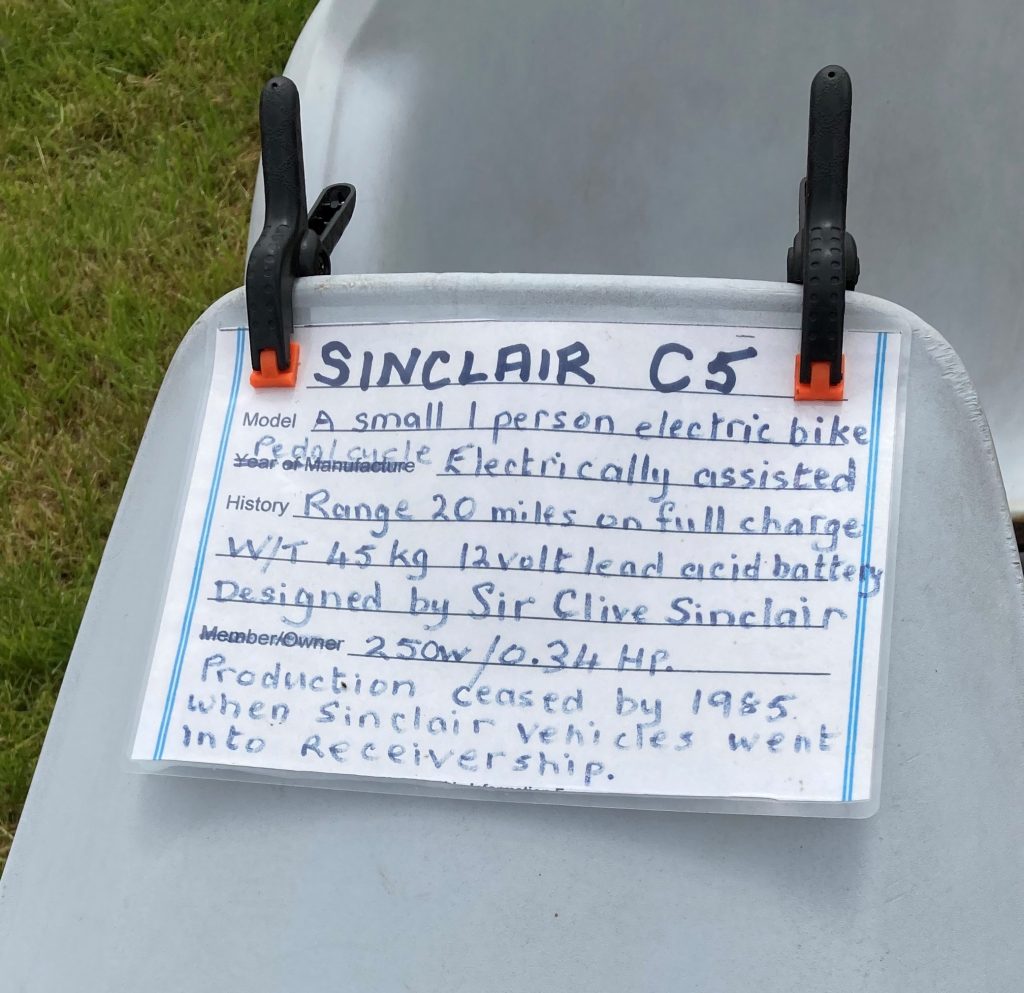

This is a Sinclair C5, mocked by many as a great British failure, but maybe it was simply ahead of its time.

Technically described as an ‘electrically assisted pedal cycle’ and widely called an electric car, it was developed by the computer pioneer Sir Clive Sinclair. It had a polypropylene body, a steel chassis designed by Lotus, and a motor designed to power a fan (not a washing machine, as was often said). The driver sat in a leaning position, steering via a handlebar under the knees and if necessary contributing to the motor power with pedals. There was no reverse gear so if you wanted to turn round you got out, picked up the front end and swung it round.

Among the selling points was that you didn’t need a driving licence (though you had to be at least 14) or to pay road tax. Here is the original TV ad:

It sold for £399 but ‘optional’ extras included indicator lights, mirrors, a horn, and a reflective strip on a pole designed to make the C5 more visible in traffic.

The brochure noted that ‘the British climate isn’t always ideal for wind-in-the-hair driving’ and offered a range of waterproofs including the poncho which you can see a happy-looking soul demonstrating here.

The C5 was launched at Alexandra Palace on January 10, 1985. Here is the News at Ten report. (Quiz question: Who is the newscaster?)

Almost immediately it bombed. Critics pointed to the short range (20 miles), the limited speed (15mph) and most of all the vulnerability of such a tiny vehicle and its driver/rider in road traffic. Out of 14,000 C5s made, only 5,000 were sold before Sinclair Vehicles went into receivership.

Yet now it has a cult following. There are owners’ clubs such as this one and some enthusiasts have modified their vehicles, for example this one at a drag racing meeting.

Here is a C5 rally.

And last but not least a clip from the Kenny Everett Television Show in 1985, featuring newsreader Peter Woods.