EARLIER this month I popped into a petrol station to get a poppy for Remembrance Day. Not having any cash, I asked the cashier if I could somehow do it via card. He looked at me blankly. I explained again, saying that I didn’t have any change for the collection jar.

‘I have no idea what those are, I have only just noticed them,’ he said, referring to the tray of poppies two feet in front of him. ‘No idea at all?’ I asked, bemused. He nodded in assent.

‘They’re to commemorate the millions who have lost their lives in conflict,’ I was forced to say, slightly astonished that the point had to be made. I told him I would make the donation online and went on my way.

At the time this happened I thought it merely another symptom of Britain’s shifting cultural landscape, undergoing as we are the greatest demographic shift since the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain. The chap was of foreign origin, from somewhere between Pakistan and Bangladesh if I had to hazard a guess.

‘Integration’ is one of those words that is thrown around, usually with some unsatisfactory referencing of ‘British values’, a nebulous set of attributes and standards that once never needed defining but are now impossible to pin down due to the many-decades dilution of Britishness, the hammering of the people’s psyche and the slandering of their history.

Perhaps ‘absorption’ is a more preferable term. Nobody cares how many Huguenots arrived in the country hundreds of years ago because they have been absorbed fully. Nobody would care that I had a foreign grandparent because after just one generation her progeny were as English as the next.

And perhaps, had the petrol station cashier been working as a brain surgeon or theorist in quantum physics, I would have been more inclined to let it slide. After all, such individuals bring rare and world-leading talents to the table. However, the man in question was working at a BP station. There is no doubt that someone already here could fill that job, even more so were it not for the wage-suppressing effects of many decades of importing foreign labour.

Absorption can take place only at a certain rate. As the ground can only absorb so much water after a rainstorm before it is swamped, so too the population. This absorption becomes more difficult when the differences between people are greater due to their cultural, social or religious beliefs. Much sooner would 100,000 Danes be fully absorbed than 100,000 Afghans.

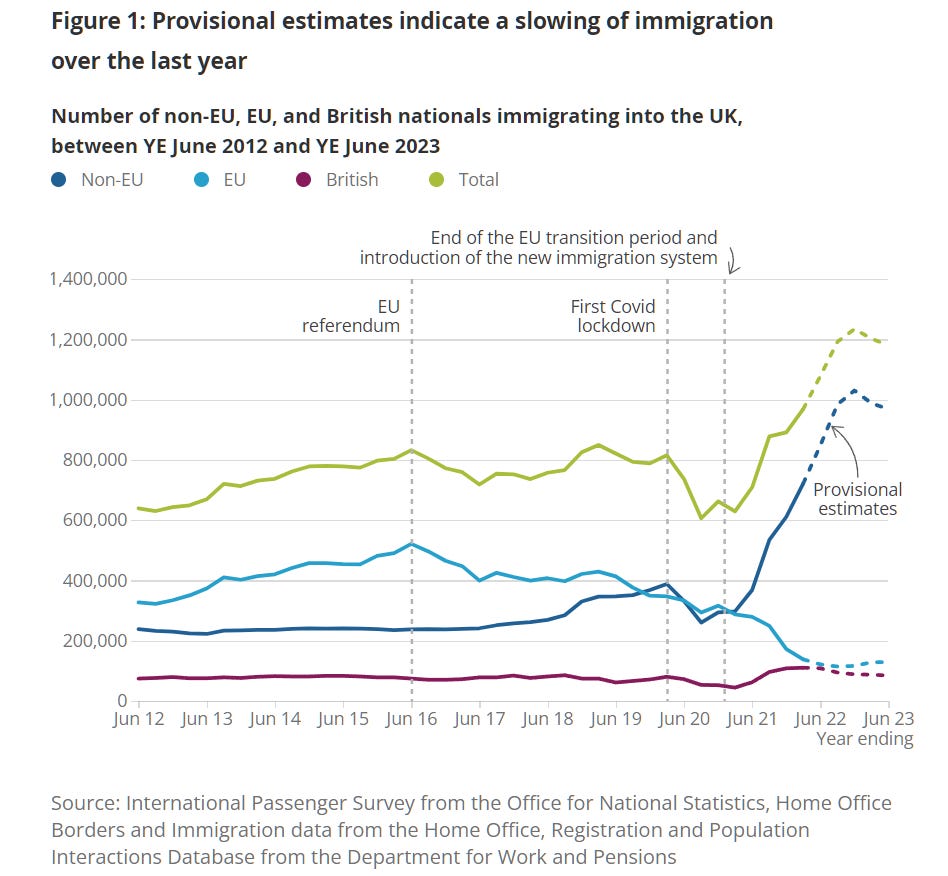

The release of recent immigration figures brings such concerns once to the fore. The significance of the figures contrasted neatly with the lack of importance afford to them by the mainstream media: had you not checked the news the day they were released, there is a good chance you would have missed the fact that the UK imported the equivalent population of Sheffield last year and of Belfast this year, the majority of whom were not EU or Westernised citizens.

Consequences arising from these drastic changes – accelerated by the departure of British nationals from blighted Blighty – are visible for all to see. One need not go to Birmingham, London or Manchester to witness the rapid changes to our country, for the effects are now clear in England’s smaller towns. In my corner of the Midlands, the number of Africans has grown dramatically in recent years, augmented by a smattering of Ukrainians, together with every other nation under the sun.

By now it is trite to say such radical demographic changes will lead to trouble. Much of the damage is already there, but those wedded to our modern-day orthodoxies refuse to speak their name. For each side-effect – for example the unaffordability of property and the over-stretching of public services – a dozen other reasons are found to blame. Maybe it’s true that the NHS is junk partly because of a lack of funding, but it ought not be a taboo in polite society to recognise that mass population growth is partly to blame for this.

To focus on the economic, of course, is to fall into the modern trap, where immigration’s benefit or detriment is gauged only by a flickering of the dial of our GDP. That which matters more over the duration – the cultural and the social – is naturally harder to quantify and less pleasant to discuss, and so it is kept hushed up.

Nevertheless, I remain of the conviction that nothing in our national equation will change until we are struck by some calamity, most likely of the economic variety. A Black Swan event will make the current social contract unviable, kicking away the struts that hold up our rickety modern compromise. Elsewhere there are signs of this untenability bubbling away already, with Dublin aflame after the stabbing of Irish children on its streets, and Geert Wilders’s recent triumph in the Dutch elections.

But for now, power remains firmly in the hands of the people who orchestrated this fine mess. As time moves on, the balance continues to shift in their favour as the globalist cookie-cutter revokes each Western nation’s right to its individual character in favour of a 21st century Tower of Babel.

Things will get worse before they get better, but our story is one of triumph against the odds. These small islands went from obscurity to the world’s foremost power. It is this latter success which has fed our complacency. I have a gut feeling that a nasty dose of reality will bring us rapidly to the needed level of sobriety. The only concern is the extent of what will have to be done to get us back on track when that finally occurs.

This article appeared on Frederick’s Newsletter on November 27, 2023, and is republished by kind permission.