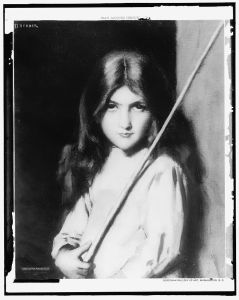

“I studied that girl, Joan of Arc, for twelve years,” Mark Twain said, “and it never seemed to me that the artists and the writers gave us a true picture of her. They drew a picture of a peasant. But they always missed the face—the divine soul, the pure character, the supreme woman, the wonderful girl.”

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431), the Maid of Orleans, virgin and martyr, patron saint of soldiers and one of the patron saints of France…

Saint Joan of Arc (1412-1431), the Maid of Orleans, virgin and martyr, patron saint of soldiers and one of the patron saints of France…

Her basic story is legend: how during little more than a year of hearing her holy “voices,” the scarcely-educated farm-girl led her nation and her faith to repeated victories on the battlefield and how only a year after that, at age 19, she was burnt alive. Her corrupt, politicised conviction, at the hands of foreign invaders, was overturned a quarter-century later by Pope Callixtus III, but she was beatified only in 1909 and canonised just within living memory in 1920.

Her recent canonisation may seem surprising for she seems to have been among us forever, and in some ways she has been popular and venerated for almost 600 years. But her celebrity accelerated in the mid-Nineteenth Century, thanks partly to a now-forgotten historian and a famous American author, Mark Twain.

Within Joan’s lifetime Christine de Pizan penned an elegiac poem to her. By 1590 and renamed Joan le Pucelle, Shakespeare wrote her into Henry VI, Part 1 as a falsely pious witch put to death, doubtless popular among Tudor England’s Francophobe, Protestant, ticket-buying audiences.

She was again abducted, this time by the Enlightenment in 1756 as The Maid of Oranges (instead of Orleans), in an anti-religious satire by Voltaire. Schiller leaped to her rescue in 1801, but the commercial and cultural demands of High Romanticism made him turn her into a pre-Wagnerian, giving her a magic helmet, playing down religion and killing her off in battle instead of at the stake. Only the Valkyrie’s tin brassiere seems to have been omitted.

The French historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874) may have been among the first to contaminate his craft with his own Romantic Age feelings and personality, rather as dubious film-makers now write themselves into their documentaries ahistorically. His epic, multi-volume, Histoire de France treats “Joan of Arc as the very soul of France and the living symbol of his own patriotic and democratic ideals” that culminate, curiously enough, in the secularist Revolution and Reign of Terror. Yet again, poor Joan was made into an ideological hobby-horse.

In real life, she broke her sword (possibly a Dark Ages relic of Charles Martel) by whacking prostitutes on their backsides to drive them from her army camps: we must wait for the next world to see what she has done to her literary hijackers.

Temporal justice returned with Jules Etienne Joseph Quicherat (1814-1882), a far more dispassionate historian who, inspired by Michelet, nevertheless translated and published the court proceedings against Joan and several related works that remain seminal.

Cleopatra’s last words, recorded faithfully by her contemporary Strabo, survive through Shakespeare to Elizabeth Taylor on screen, but even this marvel fails to compete. From an historian’s perspective Quicherat struck a gold-mine, for not only were the voluminous court minutes intact but so was later testimony from virtually anyone who ever met her, including her family and childhood friends, gathered for the papal retrial that overturned her heresy conviction a mere quarter-century after her martyrdom.

One historian brought Saint Joan back to life. Every snide allegation was dispelled as modern audiences could read the trick questions leveled so confusedly by her persecutors, revel in her thoughtful and convincing but clearly unschooled answers, and see the testimony of those who knew her—from the pastures to which she longed to return, to her year in armour bearing a sword that she never used to kill, to her final hours of suffering and faith.

Few characters of the Late Middle Ages leave such a thorough historical record, and few ever at least until the last century. Mark Twain wrote:

The Official Record of the Trials and Rehabilitation of Joan of Arc is the most remarkable history that exists in any language; yet there are few people in the world who can say they have read it: in England and America it has hardly been heard of…. Three hundred years ago Shakespeare did not know the true story of Joan of Arc; in his day it was unknown even in France. For four hundred years it existed rather as a vaguely defined romance than as definite and authentic history. The true story remained buried in the official archives of France from the Rehabilitation of 1456 until Quicherat dug it out and gave it to the world two generations ago, in lucid and understandable modern French.

Twain read Quicherat and became fascinated by Joan, spending more than a decade researching and writing his historical novel, Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, which was serialised by Harper’s Magazine in 1895 and published as a book a year later.

Although it is obscure today, he thought it far better than Tom Sawyer or Huckleberry Finn, recalling: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books… It furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.”

After studying files in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Twain wrote a deeply emotional book devoid of his trademark humour, because:

Taking into account…all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.

It is unexpected praise from such a notorious sceptic and warrants examination.

Championed by modern atheists as one of their own, Twain’s own writings show that he was nothing of the sort although the devout misanthrope had no fondness for organised religion.

He failed, also, to reconcile the God of the Old Testament to the New, writing to his beloved wife Olivia, “I am plenty safe enough in his hands; I am not in any danger from that kind of a Deity. The one that I want to keep out of the reach of is the caricature of him which one finds in the Bible,” and later in a notebook, “God, so atrocious in the Old Testament, so attractive in the New—the Jekyl and Hyde of sacred romance.” The words of a Deist, perhaps, but hardly of an atheist.

Yet Twain’s scepticism makes it hard to understand his devotion to Joan, who stripped of her faith and the miracles attendant becomes simply an historical curiosity. Twain confessed:

Privately, I myself never had a high opinion of Joan’s Voices —I mean in some respects—but that they were devils I do not believe. I think they were saints, holy & pure & well meaning, but with the saint’s natural incapacity for business. Whatever a saint is, he is not clever. There are acres of history to prove it. … The voices meant Joan nothing but good, & I am sure they did the very best they could with their equipment; but I also feel sure that if they had let her alone her matters would sometimes have gone much better. Remember, these things I have been saying are privacies — let them go no further; for I have no more desire to be damned than another.

Elsewhere he wrote that Joan’s dazzling military and rhetorical prowess were no more normally explainable than her otherwise baffling but precise predictions of the timing of her martyrdom and other events foretold, she said, by Saints Margaret, Catherine of Alexandria, and the Archangel Michael.

Twain was no atheist but his faith was parlous small. So the answer may be as simple as Saint Augustine’s comment “Nisi creditderitis, non intelligetis,” or “unless you have believed you will not understand.” Yet that provides no satisfactory explanation of how a practicing cynic can fall at the feet of a saint without him acquiring faith.

An old photograph and a yellowed newspaper clipping from The New York Times shows the mysterious depth of Twain’s emotional and even a (dare one say?) spiritual capture by the Holy Maid. The newspaper reported a supper held on New Year’s Eve, 1905:

Mark Twain was the guest of honor at a dinner given last night at the Aldine Association by the Society of Illustrators. All the well-known magazine and newspaper artists were present, while other distinguished guests included Andrew Carnegie… Arthur Scribner… Frederick Remington… and Daniel Beard…. It had been arranged that when the humorist arose to speak Miss Angersten, a well-known model, was to appear in the garb and with the simple dignity of Jean d’Arc, his favorite character in all history. He was on his feet as Jean d’Arc entered the room. She wore the armor of the French heroine and her hair and face made a strangely appealing picture.

The face of the humorist, which had been wearing its “company” smile all night, suddenly changed. He had every appearance of a man who had seen a ghost. His eyes fairly started out of his head, and his hand gripped the edge of the table. Jean d’Arc presented him with a wreath of bay. He merely bowed, with his eyes fixed on the girl’s face. They followed her as in reverent silence she passed out, followed by a little boy in suitable costume, bearing a banner over her head. Then Mark Twain spoke. His voice was broken, and his word came slowly.

“There’s an illustration, gentlemen—a real illustration,” he said. “I studied that girl, Joan of Arc, for twelve years, and it never seemed to me that the artists and the writers gave us a true picture of her. They drew a picture of a peasant. Her dress was that of a peasant. But they always missed the face—the divine soul, the pure character, the supreme woman, the wonderful girl. She was only 18 years old, but put into a breast like hers a heart like hers and I think, gentlemen, you would have a girl—like that.”

The humorist looked toward the door, and there was absolute silence—puzzled silence—for many did not know whether it was time to laugh, disrespectful to giggle, or discourteous to keep solemn. The humorist realized the situation. Turning to his audience he came out of the clouds and said solemnly: “But the artists always paint her with a face—like a ham.”

He quickly regained his composure and delivered the expected wise-crack, but for a moment the old cynic, who rather doubted saints, thought that he beheld one and it stopped him in his tracks.

For an explanation we can turn, typically, to G. K. Chesterton who was Twain’s contemporary albeit a generation younger. Chesterton contrasted Saint Joan to Tolstoy and Nietzsche:

Joan, when I came to think of her, had in her all that was true either in Tolstoy or Nietzsche, all that was even tolerable in either of them. I thought of all that is noble in Tolstoy, the pleasure in plain things, especially in plain pity, the actualities of the earth, the reverence for the poor, the dignity of the bowed back. Joan of Arc had all that and with this great addition, that she endured poverty as well as admiring it; whereas Tolstoy is only a typical aristocrat trying to find out its secret. And then I thought of all that was brave and proud and pathetic in poor Nietzsche, and his mutiny against the emptiness and timidity of our time. I thought of his cry for the ecstatic equilibrium of danger, his hunger for the rush of great horses, his cry to arms. Well, Joan of Arc had all that, and again with this difference, that she did not praise fighting, but fought. We know that she was not afraid of an army, while Nietzsche, for all we know, was afraid of a cow. Tolstoy only praised the peasant; she was the peasant. Nietzsche only praised the warrior; she was the warrior. She beat them both at their own antagonistic ideals; she was more gentle than the one, more violent than the other. Yet she was a perfectly practical person who did something, while they are wild speculators who do nothing. It was impossible that the thought should not cross my mind that she and her faith had perhaps some secret of moral unity and utility that has been lost. And with that thought came a larger one, and the colossal figure of her Master had also crossed the theatre of my thoughts.

Chesterton gives us a valuable insight that would be accessible to any Christian mystical poet, to the Zen masters analysed by the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, or to devotees of the Chinese Tao. That is the nature of being and doing which is clear to anyone of faith or deep spiritual understanding. It would be immediately understandable to Our Lady, who upon receiving the Annunciation had to decide if she was mad or, if not, to just get on with it.

Saint Joan’s decision can be reached by faith or analysis, but modernity offers greater chance for prevarication and dithering. Her surety and action expressed to Mark Twain a reality partly denied to those lacking faith and the Grace that conveys it; to those overly reliant upon reason to the exclusion of all else.

We might benefit from faith and reason as she did, just get on with it and do what we ought. Those who do win nations, save belief from its enemies, and do so with power brought from far beyond our paltry selves.

It may be that, for Mark Twain and for us all, the ever-active Maid and the Holy Spirit intercede for those who just get on with it, and even those who can only admire it in others.

This essay was first published here in January 2012.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a depiction of Joan of Arc in infancy by Henner, Jean-Jacques, 1829-1905, and is courtesy of Picryl.