When man pursues beauty, he takes it into himself and becomes beautiful through it; a perpetual beauty-seeker, such as Don Quixote, is, therefore, a beautiful man.

He conceived the strangest notion that ever took shape in a madman’s head, considering it desirable and necessary, both for the increase of his honor and the common good, to become a knight errant, and to travel about the world with his armor and his arms and his horse in search of adventures.[1]

He conceived the strangest notion that ever took shape in a madman’s head, considering it desirable and necessary, both for the increase of his honor and the common good, to become a knight errant, and to travel about the world with his armor and his arms and his horse in search of adventures.[1]

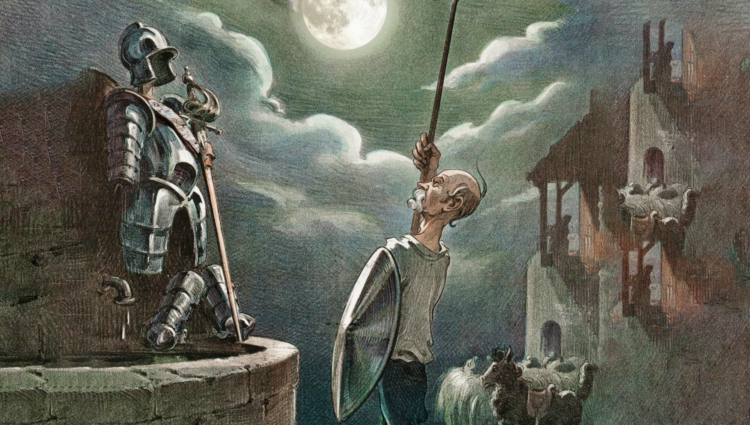

Cervantes’s Don Quixote has an urgent desire to encounter beauty. Wishing to know essentially the most wonderful things of the world, and through those encounters to become more beautiful himself, he is drawn to act—to name, to fight, to love, to do something worth doing. Through difficult trials, his spirit remains indomitable, but not in the sense of William Ernest Henley’s “unconquerable soul,” for this strength is not autonomous, but instead rooted in a knowledge of the good.[2] To some, Don Quixote is “a madman” with strange notions and archaic tendencies. Indeed, he is mad. However, his actions arise from a madness of a certain sort, a madness for “honor and the common good.” Unsatisfied with merely reading about feats of chivalry, Don Quixote quests after them, seeking a personal engagement, down to the glorious details of “his armor and his arms and his horse.” His own beauty is caused by his mad desire for the beautiful.

To say what exactly that beauty is, however, proves a challenging task; one need only read a little Plato to see how many definitions are possible for “the beautiful.” Aquinas offers at least a useful definition in respect to the effect which beauty has on the observer: “id quod visum placet.”[3] What is beautiful is more than simply true and intelligible, although that is necessary; it must also be pleasing. In agreement with Aquinas, French philosopher Jacques Maritain writes that a beautiful thing is inherently desirable: “Therefore by its nature, by its very beauty, it stirs desire and produces love, whereas truth as such only illuminates.”[4] Beauty is fundamentally composed of truth and attraction, both of which must be recognized for the object to be seen as beautiful.

When he esteems chivalry as highly as he does, Don Quixote is exhibiting a similar view of “the beautiful.” The habit of chivalry is based in truth, for it deals with the essence of things, viewing women as women, men as men, and monsters as monsters. Chivalry is more than this, however; it is an expression of love, that other requirement for beauty. When the object of chivalry is loved, it draws its lover to itself, sharing of its beauty. We see that this principle can also find a deeper expression than chivalry, for the perfection of love is found in God, its source. God knew and loved and pursued us, the most beautiful creation, to the point of becoming one of us, and we love and pursue Him and in that degree become deified and beautiful in Him. Imitating the motion of divine love, then, Don Quixote sees things that are true, sees them as beautiful, and in pursuing them, rises to partake in them.

The lover becoming more like his beloved is the basis of our knight’s defense of chivalry, which he offers to the canon of Toledo:

It is clear that any passage from any history of a knight errant is bound to delight and amaze anyone who reads it.… you will soon see how they banish any melancholy you might be feeling, and improve your disposition, if it is a bad one. Speaking for myself, I can say that ever since I became a knight errant I have been courageous, polite, generous, well-bred, magnanimous, courteous, bold, patient… (DQ, 458).

Chivalry and tales of it, therefore, dispose man to virtue, drawing him into closer union with the people and things which he loves, the things which “delight and amaze” him. To the extent that a chivalric knight becomes more like a beautiful thing and begins to understand it for what it really is, he cannot help treating it well and virtuously, as a part of himself which is good and noble.

This deep knowledge of reality is essential to the recognition of, and eventual union with, beauty. Quixote, much like Adam in the garden, has a special insight into the essence of things, and takes it upon himself to name them, including his own beloved lady:

She was called Aldonza Lorenzo, and this was the woman upon whom it seemed appropriate to confer the title of the lady of his thoughts; and seeking a name with some affinity with his own, which would also suggest the name of a princess and a fine lady, he decided to call her Dulcinea del Toboso, because she was a native of El Toboso: a name that, in his opinion, was musical and magical and meaningful, like all the other names he’d bestowed upon himself and his possessions (DQ, 29).

“The lady of his thoughts”—this is a noble idea in itself, for he wishes to contemplate always the good of a woman, the woman he loves. Following the custom of his mentors, the amorous knights of days past, he disdains food and sleep, lesser goods compared to lengthy meditation upon the beauty of Dulcinea de Toboso, with a hundred years, as Marvell writes, “to praise / thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; / two hundred to adore each breast; / but thirty thousand to the rest.”[5] Indeed, he holds the love of woman to be one of man’s greatest goods, and thus wishes to name his lady in relation to himself (DQ, 171). Because his identity is linked to hers, she deserves a “name with some affinity with his own.” This name will reflect where she is from and thence who she is, a “native of El Toboso.” Finally, in a striking alliteration her name must be “musical, magical, and meaningful.” In other words, the name is reflective of his lady’s wonderful nature. A name, when given with the care that Don Quixote exercises, is a window into the subject’s inner truth and essence—it displays the inherent beauty.

In a similar manner, before he can begin his expedition, our explorer takes great care to name his horse:

He spent four days considering what name to give the nag…he finally decided to call it Rocinante, that is Hackafore, a name which, in his opinion, was lofty and sonorous and expressed what the creature had been when it was a humble hack, before it became what it was now (DQ, 28).

Here is illustrated his mount’s history: The name of Rocinante, sounding “lofty and sonorous,” expresses the movement and purpose of the horse’s life, what it had done and what it does now.

We again see Don Quixote’s obsession with the power of names when he leads his friends into shepherding: our beloved simpleton assures them that there is little preparation necessary for their new pursuit other than finding appropriate shepherd titles: “The most essential part of the business was already settled, because he’d provided them with names that would fit like gloves” (DQ, 973). The naming links them with the act, for if you have a proper shepherd name, you are already more than halfway to being one. Really good names, ones that “fit like gloves,” are the expressed essences of the things they name, and knowing them is, therefore, the first and most important step to embracing the realities which they signify. Don Quixote, in naming people and things essentially, joins himself to them as instances of the beautiful.

Focused on truly good things, he is not easily distracted by trivial matters, even if the world considers them important. In a manner reminiscent of the instructions given to those other travelers—“He ordered them to take nothing for their journey except a staff; no bread, no bag, no money in their belts”[6]—Don Quixote laughably neglects to bring money on his first foray, trusting that chivalry and good-will would be sufficient (DQ, 37). Again, despite suffering numerous bludgeoning, he never seems to give them too much weight, accepting them as necessary nuisances on his journey of chivalry. Even his squire Sancho eventually learns from him to take a phlegmatic attitude to such beatings and inconveniences. We see this attitude explicitly when Don Quixote hears the crimes of the prisoners he encounters; he considers it “excessively harsh to make slaves of those whom God and nature made free,” and tells their guards to let them go and “let each answer for his sins in the other world” (DQ, 183). Their crimes are, to him, secondary to their worth as human beings, so he disregards the sins and frees the men. So also, when lying on his deathbed, he realizes that chivalry itself, is not the most beautiful thing he can achieve, so he pushes it aside for an even greater end, to be “Alonso Quixano the Good.” He does not cease to desire beauty, but simply concentrates on dying a holy death.[7] Here, too, he is not distracted by lesser things, but strives always after the most beautiful object he can see in the moment.

Some might accuse this errant knight of wandering aimlessly without a particular good in mind; “errant”, after all, has its root in errare, “to stray at random.”[8] In a certain respect, it is true that Don Quixote does not have a particular individual good in mind, but he does pursue a particular kind of good. He knows what sort of good he is seeking, the love and defense of beautiful things, and where it is to be found, in adventure. He does not know exactly which adventure will be found, only that it will be found by a wanderer, by an errant. He rides through the Spanish countryside, then, in search for the beautiful, which is more beautiful precisely because it is unknown beforehand; it always appears as a surprise, almost as if heavenly ordained for him.

Don Quixote gives some indication of the strength of his desire for beauty in the adventure with the lions. Lions really are terrible monsters; it is foolish to forget this. Don Quixote, however, is not foolish, but, as his squire says, “only reckless” (DQ, 593). Falling in with a cart with caged lions, he decides that, as a knight, it is only right that he should show his courage and challenge the beasts. He “took up his shield, drew his sword and advanced with a slow and steady step, with wonderful courage and a valiant heart” (DQ, 595). Because of this “resolve and courage,” with the battle over, the victorious challenger renames himself the “Knight of the Lions.” His desire is so strong for knightly things, for feats of strength and noble bearing, that he will muster the courage to fight what he considers to be the largest lions in Europe to attain them (DQ, 597).

Recognition of beauty, if it does not lead to lion-fighting in every case—although it will for some—is always heroic. It requires two things: knowledge and love. When man pursues beauty, he takes it into himself and becomes beautiful through it; a perpetual beauty-seeker, such as Don Quixote, is, therefore, a beautiful man. In the course of naming Dulcinea de Toboso, Rocinante, and his other friends, Quixote becomes aware of what they really are and, knowing them as good and pleasing, embraces them. He leads a fantastical, errant life, but he does so by continually jumping into adventures for beauty, soaking in its pools wherever he can find them. Even if Don Quixote is insane, he causes the rest of us to rethink our sanity.

This essay was first published here in November 2017.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Cervantes, Don Quixote (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 27.

[2] William Ernest Henley, “Invictus” The Poetry Foundation. (Accessed 31 Oct 2017).

[3] That which, seen, pleases. (Summa Theologica, i. q. a. 4, ad 1.)

[4] Jacques Maritain, Art and Scholasticism, trans. J.F. Scanlan (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1946), 21.

[5] Andrew Marvell, Andrew Marvell: Poems, ed. George deF Lord (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), “To his Coy Mistress.”

[6] Mark 6:8, NRSVCE

[7] In this respect, Quixote’s rejection of chivalry is similar to St. Augustine’s rejection of his previous, pagan education, following his conversion. In both cases, despite the strongly expressed feelings of regret, it would be impossible for them to completely deny the real good which was present in their earlier lives. They can only treat their past harshly in relation to their new-found higher ends.

[8] The Oxford English Dictionary (New York: Oxford University Press, 1961).

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.