Something about the way in which metaphysical poetry engages the mind is unique to this style of verse. A combination of relatable simplicity with conceptual eclecticism renders it into a form of expression that can be deeply and personally felt by the reader, but only once he works through the poet’s intricate analogies and “metaphysical” concepts. Such poetry is seldom direct and easy to decipher, which is what makes it so intellectually stimulating to read. The point to reading metaphysical poetry is acknowledging that the themes it presents are explained through unusual metaphors and analogies that would not come intuitively to us if we were striving for comparative accuracy. If, however, we are seeking novelty in perspective that turns the strangest idea into the most astute depiction of the human experience, then it is truly one of the most underrated forms of poetry deserving of greater praise. Put another way, the “conceit” used by most metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century deliberately compares apples to oranges, and does a wonderful job at it that it opens our mind to new discoveries about our relationship with the world.

Something about the way in which metaphysical poetry engages the mind is unique to this style of verse. A combination of relatable simplicity with conceptual eclecticism renders it into a form of expression that can be deeply and personally felt by the reader, but only once he works through the poet’s intricate analogies and “metaphysical” concepts. Such poetry is seldom direct and easy to decipher, which is what makes it so intellectually stimulating to read. The point to reading metaphysical poetry is acknowledging that the themes it presents are explained through unusual metaphors and analogies that would not come intuitively to us if we were striving for comparative accuracy. If, however, we are seeking novelty in perspective that turns the strangest idea into the most astute depiction of the human experience, then it is truly one of the most underrated forms of poetry deserving of greater praise. Put another way, the “conceit” used by most metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century deliberately compares apples to oranges, and does a wonderful job at it that it opens our mind to new discoveries about our relationship with the world.

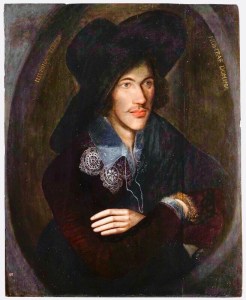

This essay proposes an exploration of such poetry through one of its masters, John Donne, on that ubiquitous theme, love. But first it helps to analyze the mind of the metaphysical poet more closely. In his 1921 essay, “The Metaphysical Poets,” T.S Eliot wrote,

When a poet’s mind is perfectly equipped for its work, it is constantly amalgamating disparate experience; the ordinary man’s experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary. The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these two experiences have nothing to do with each other, or with the noise of the typewriter or the smell of cooking; in the mind of the poet these experiences are always forming new wholes.[1]

Disparate experience in the mind of the metaphysical poet is not disconnected at all: When analyzed and felt at their core there is a commonality amidst their disparity that renders the sentiment complete and open to new exploration through new possibilities for further experience. This resourceful and creative frame of mind is unique to the poet, and it turns our little world into a vast realm of self-discovery. Eliot suggests that the role that experience played for metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century was connected to the historical age in which they were living and to the literary influences they had been bequeathed. These poets who were “the successors of the dramatists of the sixteenth [century], possessed a mechanism of sensibility which could devour any kind of experience.” They were hyper-receptive to various forms of emotion since they encountered the world with the entirety of their senses, never dismissing the possibility that even the most mundane of things (a flea, perhaps?) could be turned into the most fitting literary muse to relay sentiment.[2]

For a case in point, we can turn to John Donne’s poem “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” The metaphysical element is persistent throughout the poem, layering simile upon metaphor upon simile to create a long analogy for the bond between two lovers that evolves as the poet himself tries to find the perfect way to convey his message. The first stanza of the poem describes the valiant and admirable character of “virtuous men” (1) who, in the process of death, “whisper to their souls to go” (2) in silence to themselves even while people around them still ponder if they’ve died. In this stanza, Donne introduces a sense of personal peace that comes with knowing oneself, ignoring what those around might be conjecturing. In this fashion, the poet writes in the second stanza that he and his lover must “melt, and make no noise” (5); internalizing their pain because it would be a “profanation” (7) of their joys and true love to do otherwise and externally manifest their emotions to “the laity” (8)—to people who are not worthy of witnessing such strong a relationship, much less understanding it.

So far, the poet is comparing the integrity of his love to the strong character of virtuous men at death to emphasize the stoic demeanor that he and his beloved must display. The third stanza introduces a new metaphor, the geological phenomenon of earthquakes, to describe this emotional farewell between the couple. The poet writes that earthquakes cause “harms and fears” (9), leading men to hypothesize about what such a visible and natural tragedy can mean (10). This metaphor is a parallel for what would happen if the poet and his beloved were to outwardly show their sorrows, stirring unrest and raising questions in those people watching them. The poet now introduces another metaphor, the “trepidation of the spheres” (11), or the moving of the celestial planets. The scale of movement has increased from an earthquake to planetary rotations, and the poet writes that, ironically enough, the movement of planets “though greater far” than the movement caused by an earthquake, is “innocent,” undetected and unfelt, by men (12). This observation is meant to prove a point: The havoc wreaked by an earthquake is easy for people to talk about and to analyze, but they are living inside a far greater mystery that they cannot understand. The poet is expanding on the point of his previous stanza, which told his lover that they should not expose their feelings for people who do not matter: A woeful valediction would make their emotions resemble an earthquake, when in reality, the magnitude of their love is so much greater, that it compares to the movement of planets in the universe, which the detached passerby cannot detect.

The fourth stanza continues to expand on this metaphor that compares the straightforwardness of geology with the complexity of astronomy. “Dull sublunary lover’s love” (take a moment to appreciate the pleasing consonance used in this line) expresses how lovers who live beneath the moon, beneath the solar system, have a “dull” form of love. Their love is superficial, based on physical displays of emotion. Such an elementary love has a soul that is comprised of “sense” (14)—sensory experience—which is why it cannot “admit absence,”; “because it doth remove / Those things which elemented it.” (15-16) Only those with a rudimentary type of love have a hard time dealing with absence, since it removes the ability for that superficial and physical closeness that ignited it in the first place.

The fifth stanza changes the metaphor from astronomical and geological references and instead begins to play on the “elements” that comprise love. The poet writes that he and his beloved have a love “so much refined, / That our selves know not what it is,” (17-18). But because they are so “inter-assured of the mind” (19); so internally convinced of what is between them, they could care less to miss those trivial things like each other’s eyes, lips, and hands (20). The poet reaches the climax of his poem, and the true meaning of his convoluted analogies, in the sixth stanza:

Our two souls therefore, which are one,

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion,

Like gold to airy thinness beat. (21-24)

The two lovers share a soul, and despite the fact that the poet must depart, he promises his beloved that they are not enduring a breach. Their love is made of gold, because this valuable element is malleable; so much so, that it can be flatted, “to airy thinness.” This image of something resembling the metallic properties of gold, able to be flattened into a sheer foil, creates a conception of such a refined love that, due to its strength, is itself an element as pure as gold. Up to this point, the poet has used several forms of similes and metaphors which demonstrate Eliot’s point about the poet pulling from various (disparate) experiences and seeing in them a cohesive explanation about a particular sentiment, in this case love. The seventh stanza continues to place experience upon experience, introducing yet another simile.

Donne has already admitted that he views his soul and the soul of his beloved as one. But he adds another proposition: “If [our souls] be two,” they are two “as stiff twin compasses are two” (25-26), because his lover’s soul is the “fixed foot” (27) that remains unmoved unless the other foot of the compass moves (28). That fixed foot remains at the center while the other one roams around it (29), displaying its affection for its drifting companion as it “leans and hearkens” (31) after it when it is far, but straightening out once the other foot “comes home” (32). The final stanza of the poem finishes this metaphor of lovers being like a compass by expressing, finally and fully, what the poet means to say:

Such wilt thou be to me, who must,

Like th’ other foot, obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end where I begun. (33-36)

The beauty in this metaphor is that the poet is reassuring his love that her firmness is what keeps his movement—his circle—just, knowing he will always go back to the center and be one with her. “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning” is an example of a poem that displays the layering of similes and metaphors that crafts a complex analogy. While Donne could have simply written about the likeness between his love and two compasses from the beginning, it was necessary for him to work his way up to that revelation by starting with the other, disparate experiences. All of these different themes—the dying but virtuous man, earthquakes, the universe, gold, compasses—have little to do with each other, still they manage to coherently express what Donne wanted to transmit. It is almost as though Donne is taking us with him through his thought process, allowing us to discover the meaning of his love at the same time as him.

The charm in metaphysical poetry is in the uniqueness of the conceit, because it is a literary caprice subjective to the experience of the poet; it can take as many paths as it deems necessary to arrive at its message. The mind of the seventeenth-century poet that resulted in his eclectic verse was the product of a philosophical outlook and frame of mind that helped the poet perceive the world in such a candid way. This outlook and frame of mind reflected a mental duality that was achieved by sensory contact with the external world combined with mystical introspection. But what became of poetry past the seventeenth century is a different story.

Eliot famously coined the phrase “dissociation of sensibility” to express what happened to the literary mind after this age. It happened “to the mind of England between the time of Donne or Lord Herbert of Cherbury and the time of Tennyson and Browning,” and it became “the difference between the intellectual poet and the reflective poet.” The problem with Tennyson and Browning for Eliot wasn’t that they lacked intellect, but that they did not “feel their thought as immediately as the odour of a rose.” In contrast, “A thought to Donne was an experience; it modified his sensibility.” Still, we interestingly recognize the eighteenth century as a “sentimental age,” but it was a type of sentimentality that confused romanticism with sentiment. While there is an element of subjectivity in metaphysical poetry, it is still tied to the universal human experience by virtue of the objects which become the poet’s muses. Eliot wrote that eighteenth-century poets “revolted against the ratiocinative, the descriptive; they thought and felt by fits, unbalanced; they reflected.” In this case, that balance, that duality, that metaphysical poets sought was distorted. The directionality of truth, in other words, was different: Romanticism sought to prove or validate the individual’s internal emotions through use of the external world—namely nature—while metaphysical poets found meaning in their internal thoughts through validation of the emotions they experienced with the external world. There is something noble about Donne affirming his love, to himself and to his lover, by finding a commonality between his travels and the movements of a compass. The problem of disassociation of sentiment is that it severed feeling from thought; the intellectual humility of a poet was overcome by his emotion—a dangerous leap.

Some might argue that the purpose of poetry is emotional expression. Here Eliot can correct this mistaken (or at least elementary) form of poetry: Emotional poetry tends to overemphasize the heart, which “…is not looking deep enough; Racine or Donne looked into a good deal more than the heart. One must look into the cerebral cortex, the nervous system, and the digestive tracts.” By this line, Eliot means to say that good poetry is the product of more than just emotional sentiment—it requires experiencing something with every recourse in our person. Wholly experiencing a moment allows the poet to “find the verbal equivalent for states of mind and feeling…” that conveys the complexity of an experience in simple, natural terms; through emotional precision, not elaborate language. Eliot would agree that the best poetry, to which Donne attests, is that which is simple in language but complex in thought, rather than complex in language but simple in thought. Producing poetry, whose soul is sense, that reduces the complexity of our experiences and our thoughts into just emotion makes our relationship with the world no better than the relationship between sublunary lovers; dull and unrefined.

This essay was first published in February 2019.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

1 T.S. Eliot. “The Metaphysical Poets.”

2 Donne, John. “The Flea.”

The featured image is a portrait of John Donne (c. 1595), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.