J.R.R. Tolkien believed that fairy-stories hold up a mirror to man, showing us ourselves. The mirror is not, however, any ordinary mirror; it is an extraordinary mirror, a magical or elven mirror, which doesn’t merely show us what we look like, but who we are, and not merely who we are, but who we should be and who we shouldn’t be.

What are we to make of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare’s flight of fancy and fantasy into fairyland? The great writer of fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien, didn’t make much of it, nor did he think much of it. In his famous essay “On Fairy-Stories”, Tolkien blamed Shakespeare and the poet, Michael Drayton, a contemporary of Shakespeare, for diminishing the size and status of elves and fairies to a “flower-and-butterfly minuteness… which transformed the glamour of Elfland into mere finesse, and invisibility into a fragility that could hide in a cowslip or shrink behind a blade of grass”. Singling out Drayton’s Nymphidia as one of the worst fairy-stories ever written, Tolkien lamented that the palace of Oberon has walls of spiders’ legs,

What are we to make of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare’s flight of fancy and fantasy into fairyland? The great writer of fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien, didn’t make much of it, nor did he think much of it. In his famous essay “On Fairy-Stories”, Tolkien blamed Shakespeare and the poet, Michael Drayton, a contemporary of Shakespeare, for diminishing the size and status of elves and fairies to a “flower-and-butterfly minuteness… which transformed the glamour of Elfland into mere finesse, and invisibility into a fragility that could hide in a cowslip or shrink behind a blade of grass”. Singling out Drayton’s Nymphidia as one of the worst fairy-stories ever written, Tolkien lamented that the palace of Oberon has walls of spiders’ legs,

And windows of the eyes of cats,

And for the roof, instead of slats,

Is covered with the wings of bats.

Tolkien continues, heaping derision on Drayton’s fairyland, describing with evident disdain the knight Pigwiggen riding on a frisky earwig, who sends his beloved, Queen Mab, a bracelet of emmets’ eyes. He then compares the flippancy and frivolity of Drayton’s fairyland with the gravitas inherent in the Arthurian legends: “Oberon, Mab, and Pigwiggen may be diminutive elves of fairies, as Arthur, Guinevere, and Lancelot are not; but the good and evil story of Arthur’s court is a ‘fairy-story’ rather than this tale of Oberon.” Tolkien’s preference is clearly for the gravitas of stories from the realm of Faërie, such as Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, both of which he translated, than for the levitas of Drayton’s Nymphidia or Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. With respect to the levitas of the latter, the Danish literary critic, Georg Brandes, wrote of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that it was a play in which “[t]he frontiers of Elf-land and Clown-land meet and mingle.” For Tolkien, Elf-land and Clown-land were two radically different places. They should not meet and they must never mingle.

Elsewhere, speaking specifically of Shakespeare’s depictions of fairies, Tolkien called down “a murrain [i.e., a plague or pestilence] on Will Shakespeare and his damned cobwebs”. He also wrote that “the disastrous debasement of this word [Elves], in which Shakespeare played an unforgivable part, has really overloaded it with regrettable tones, which are too much to overcome”. The reference to “damned cobwebs” was presumably an allusion to Mercutio’s famous “Queen Mab Speech” in Romeo and Juliet, in which the fairy queen is described as being no bigger than an agate stone who is drawn in a chariot made of an empty hazelnut across men’s noses while they sleep:

Her wagon-spokes made of long spinners’ legs,

The cover of the wings of grasshoppers,

The traces of the smallest spider’s web,

The collars of the moonshine’s wat’ry beams,

Her whip of cricket’s bone….

It is significant that Romeo and Juliet was written at around the same time as A Midsummer Night’s Dream, both of which probably date from 1595 or 1596, suggesting that Shakespeare had fairyland very much in mind at the time. What, however, should we think of the Bard’s dalliance with the fey folk? Should we agree with Tolkien? Does Shakespeare trivialize what should be treated seriously? Does his levitas violate the gravitas of Faërie?

Perhaps it depends on what we mean by “faërie”.

Tolkien tells us what he means by the word in his famous lecture/essay “On Fairy-Stories”:

[A] “fairy-story” is one which touches on or uses Faërie, whatever its own main purpose may be: satire, adventure, morality, fantasy. Faërie itself may perhaps most nearly be translated by Magic—but it is magic of a peculiar mood and power, at the furthest pole from the vulgar devices of the laborious, scientific, magician. There is one proviso: if there is any satire present in the tale, one thing must not be made fun of, the magic itself. That must in the story be taken seriously, neither laughed at nor explained away. Of this seriousness the medieval Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is an admirable example.

But wait a minute. Just before he offers this definition, he says something which suggests that faërie is indefinable, as elusive and as difficult to pin down as fairies themselves:

The definition of a fairy-story—what it is, or what it should be—does not, then, depend on any definition or historical account of elf or fairy, but upon the nature of Faërie: the Perilous Realm itself, and the air that blows in that country. I will not attempt to define that, nor to describe it directly. It cannot be done. Faërie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible.

As Tolkien seems to suggest that defining faërie is impossible and that the attempt to do so is as perilous as the Perilous Realm itself, it might be helpful to seek help elsewhere. In the chapter entitled “The Ethics of Elfland” in his book, Orthodoxy, G. K. Chesterton states that “fairyland is nothing but the sunny country of common sense”. It offers us a moral perspective which enables us to see our own world more clearly. “It is not earth that judges heaven,” he writes, “but heaven that judges earth; so for me at least it was not earth that criticized elfland, but elfland that criticized the earth.” Elsewhere in his own essay on fairy-stories, Tolkien seems to agree with this, stating that fairy-stories hold up a mirror to man, showing us ourselves. The mirror is not, however, any ordinary mirror; it is an extraordinary mirror, a magical or elven mirror, which doesn’t merely show us what we look like, but who we are, and not merely who we are, but who we should be and who we shouldn’t be. Those who look in such a mirror will see more than they realize, more perhaps than they want to see. Those who go through the looking glass, or through the door of the wardrobe, are entering a perilous realm. They could be changed forever by the experience. They might see who they are and realize that they are not who they should be.

Once Faërie is understood in this way, we can be as comfortable, or as perilously uncomfortable, in Shakespeare’s fairyland as we are in the world of Mother Goose or the world of Middle-earth. Tolkien should know this because he learned it at his mother’s knee. He learned that fairy-stories can lead us toward the Gospel truth, and that fairyland can lead us to the promised land. He learned the ancient truth that the road to heaven passes through the perilous realm of Faërie in which dragons must be slain. As St. Cyril of Jerusalem reminds us: “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. Beware lest he devour you. We go to the Father of Souls, but it is necessary to pass by the dragon.” Tolkien knows this and shows this. Shakespeare knows this and shows this. One shows us in Middle-earth and the other on a midsummer night. They are not the same but they show us the same. Vive le différence! Let the show go on!

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

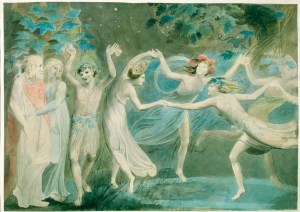

The featured image is “Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing” (c. 1786) by William Blake, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.