Make no bones about: Gustav Holst’s “The Planets” is conservative because of its deep appreciation for the sublime and the beautiful. Better yet, its conservatism can be found in its holistic and ordered approach to human emotions, as well as its unbridled love for mystery and transcendent revelation.

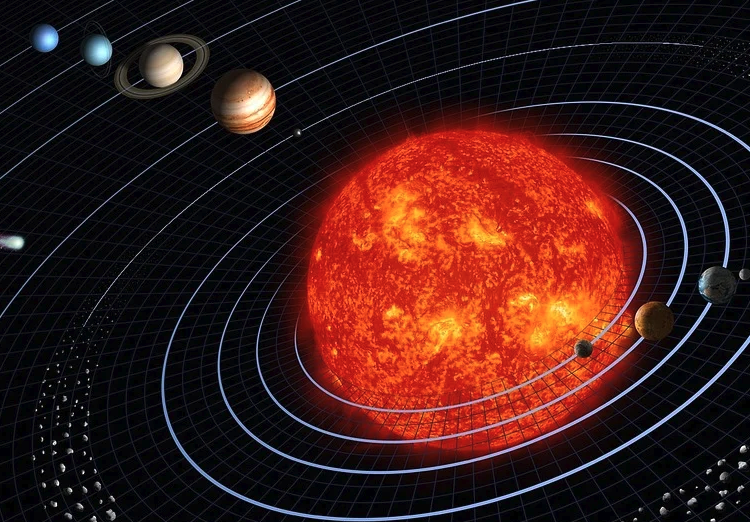

Considering that it was influenced by the hokum that is astrology, Gustav Holst’s seven-movement orchestra The Planets, Op. 32 would seem like an odd choice for a discussion topic in The Imaginative Conservative. First introduced to astrology by his friend, the journalist, poet, and playwright Clifford Bax, Holst designed The Planets as a musical expression of how each planet (barring Earth, which lacks astrological importance) influences the human psyche. From the volatility of Mars to sweet softness of Venus, Holst’s masterpiece certainly presents a sweeping study of the human heart.

Considering that it was influenced by the hokum that is astrology, Gustav Holst’s seven-movement orchestra The Planets, Op. 32 would seem like an odd choice for a discussion topic in The Imaginative Conservative. First introduced to astrology by his friend, the journalist, poet, and playwright Clifford Bax, Holst designed The Planets as a musical expression of how each planet (barring Earth, which lacks astrological importance) influences the human psyche. From the volatility of Mars to sweet softness of Venus, Holst’s masterpiece certainly presents a sweeping study of the human heart.

Considering the fact that it was written between 1914 and 1916, and then later had its first public performance at the London Symphony Orchestra in late 1920, Holst’s decision to begin his suite with “Mars, the Bringer of War” seems undoubtably influenced by the realities of World War I (although Holst always claimed that he composed the piece before the outbreak of war). A building and menacing movement that presages John Williams’ “The Imperial March,” “Mars, the Bringer of War” has all the ugly bombast of battle-scarred Belgium, with its destroyed cathedrals and ravaged population. But despite its cacophony, there is a cheery side to “Mars, Bringer of War,” almost as if the entire arrangement is intended to represent the Great War, from its effusive beginning to its cynical conclusion.

Considering the awe-inspiring power of “Mars, Bringer of War,” “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” feels a little anticlimactic. While “Mars, Bringer of War” denotes movement—sharp, precise, military-like movement, “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” constructs an idyll world—a serene sonic space that keeps an even emotional keel. While it would be easy and obvious to state that “Mars, the Bringer of War” and “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” are merely polar opposites, one could argue that a deep understanding of Edmund Burke’s distinction between the beautiful and the sublime connects the two movements to one another. In particular, while “Mars, the Bringer of War” articulates a sublime understanding of the illogical greatness of comflict (a similar sublimity was achieved by Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which, according to author Modris Eksteins in Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age, encapsulated the frenetic and chaotic spirit of the twentieth century), “Venus, the Bringer of Peace” argues for the beauty of simplicity.

In fairness, “simplicity” might be an inappropriate word to use in conjunction with The Planets. Although this suite has remained immensely popular since the 1920s, and as such it can be heard on numerous campuses throughout the world, that does not mean that The Planets is a minimalist or cheap production. A catalog of the instruments needed for Holst’s classic alone would fill an entire page of notes, whilst any orchestra looking to perform The Planets would be best served by securing an entire hall. In short, despite the gentle moments of “Neptune, the Mystic” and “Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age,” The Planets is a decidedly loud production.

Much of this can be blamed on its Romanticism. Although the background of The Planets is mired in the esoteric fads of the early twentieth century (of which included Theosophy and Ariosophy, both of which fed into the occult fetishes of National Socialism), Holst was clearly under the thrall of such Romantic composers as the Russians Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. As such, The Planets conveys a strong sense of high and low; of sadness and triumph. This makes The Planets somewhat of an anachronism, for its peers included the expressionist works of Arnold Schoenberg (who was an influence on Holst) and the feisty new art form from America known as jazz.

For whatever reason, Holst himself dismissed The Planets as rather humdrum stuff. It’s quite possible that Holst, a shy and reserved man, disliked the popularity of The Planets, and thus wrote off the entire suite as middling. Except for “Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age” (which Holst always remained partial to), Holst never considered any one of the remaining six movements to be among his best.

In a strange twist of fate, Holst is almost exclusively remembered today because of The Planets. Amateur fans of classical music can hum along to “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity,” while even those who shun concert performances like the plague can recognize and identify certain strains in each movement. And why shouldn’t they? After all, the legacy of The Planets is enormous, especially in the world of cinema scoring. As mentioned before, John Williams, who is most known for his work on Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and Saving Private Ryan, is a fan, while the lesser known British composer James Bernard (who studied under Holst’s daughter Imogen) made a career at the famed Hammer Studios by churning out dynamic scores that seem to uphold Holst as the epitome of British music.

This is quite the legacy for a musician and epoch that, until recently, was lost in the shuffle between the decline of late Romanticism and the rise of experimental music from the Continent. For the most part, British music tends to be neglected by music scholars because of its perceived stodginess. The Planets is anything but dull, and its enduring popularity is a testament to what can be achieved by conservative music. Make no bones about: The Planets is conservative because of its deep appreciation for the sublime and the beautiful. Better yet, The Planets’ conservatism can be found in its holistic and ordered approach to human emotions, as well as its unbridled love for mystery and transcendent revelation.

This essay was first published here in March 2014.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of Pixabay.