Elegance, stability, and order—as well as a sense of pure, elemental joy—are the qualities I hear in Tomaso Albinoni’s music. It is music of Venice through and through, where in the meltingly beautiful slow movements you can all but see the morning light playing on the water of the lagoon, or feel the quiet awe and majesty of the dusky interior of one of the city’s churches.

In the annals of classical music, it’s an odd fate to be best known for a work which one didn’t actually write. But such is the case with Tomaso Albinoni, the Italian composer of the Baroque period. The Adagio in G minor for strings and organ has become famous as a classical pops piece, much used in films and television and in weddings and other public ceremonies. But the piece is, in fact, not by Albinoni at all but by a 20th-century Italian musicologist named Remo Giazotto. Giazotto claimed to have based the Adagio on a manuscript fragment of Albinoni’s music salvaged from the Dresden State Library shortly after its bombing in World War II.

In the annals of classical music, it’s an odd fate to be best known for a work which one didn’t actually write. But such is the case with Tomaso Albinoni, the Italian composer of the Baroque period. The Adagio in G minor for strings and organ has become famous as a classical pops piece, much used in films and television and in weddings and other public ceremonies. But the piece is, in fact, not by Albinoni at all but by a 20th-century Italian musicologist named Remo Giazotto. Giazotto claimed to have based the Adagio on a manuscript fragment of Albinoni’s music salvaged from the Dresden State Library shortly after its bombing in World War II.

One of the reasons that Giazotto was able to perpetrate this creative fabrication is that in his time the knowledge of Baroque music among the general public (as opposed to the scholarly community) was pretty low. Since then, things have changed tremendously. The renaissance of early music, including Baroque music, since the mid-20th century has opened the door to a wealth of musical riches previously unknown. And anyone well versed in the Baroque style today will be able to recognize the Adagio for what it is: not a genuine Baroque work, but a heart-tugging post-Romantic pastiche of high Baroque style.

But who was Albinoni really, and does his genuine music sound like? It would be best to say that Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1751) forms part of the rich tapestry of music in Venice, which saw its golden age in the 17th and 18th centuries. A lifelong resident of the island city, he moved in a society that thrived on a continually replenishing palette of music for all occasions, social and religious and ceremonial. Venice was a city of color, of splendor, of strong contrasts of light and shade, and you can hear this in Albinoni’s music.

Albinoni was the son of a successful paper and playing-card merchant, and his independent wealth from the family business allowed him to live a comfortable life and write and publish when and what he wanted. Although fully professional at what he did, Albinoni insisted that he was an “amateur” (not at all a pejorative term in those times), calling himself dilettante veneto on the title pages of his works.

One of the most important art forms in Venice was the opera, and Albinoni is known to have written about 80 operas for theaters all over Italy (he also married an opera singer, named Margherita Raimondi). Most of these entertainments have been lost, however, and the same goes for many of Albinoni’s pieces of sacred music for Venice’s churches. Most of this music was never published, and so after performed once or twice from the manuscript it was laid aside and forgotten. The only music Albinoni chose to publish was instrumental, including nine collections of sonatas, concertos, and sinfonias. It is on this body of work that we are able to judge Albinoni’s skill today.

You can take the measure of this composer from his Opus 2 Sonate a cinque (for five string players plus basso continuo, the harmonic backup of the Baroque ensemble) and his concertos for oboe and strings. The Sonate a cinque are gorgeous—some of the finest examples of Baroque music for small string ensemble. Albinoni liked the oboe, and he is known as the first composer to write concertos for it. All this music is life-affirming, spiritually healthy, emotionally pure.

Italy in the Baroque era was the land of opera and also the land of the violin. The two were not unrelated. The famous families of violin makers in northern Italy—the Stradivaris, Amatis, and others—perfected the form of the violin in the late 16th and 17th centuries, and not long after players and listeners discovered the power of the violin to emulate the expressiveness of the human voice, just as the art form of opera was also coming onto the scene. Albinoni himself played the violin and put it center stage in his compositions. Here he was following the lead of Arcangelo Corelli, the “archangel of the violin,” who in Rome around the year 1700 forged a dignified, restrained, and sweetly expressive violin style as heard, for example, in his La Folia variations or his Christmas Concerto.

When I started violin lessons at the age of eight, I pretty quickly became enamored of the Baroque, with Vivaldi an instant favorite (something about the simplicity and rhythmic bounce of his music appealed to young ears, I think). Recently I have returned to my Baroque roots, both in listening and in playing, but Albinoni is now on my radar more so than before. A year or so ago I was playing an Albinoni violin sonata with my friend and colleague John Armato, an expressive player of the lute. I marveled at how good the music was: beautifully shaped and crafted, with emotional highs and lows that go straight to the heart— an inimitably Italian openness of feeling.

Elegance, stability, and order—as well as a sense of pure, elemental joy—are the qualities I hear in Albinoni’s music. It is music of Venice through and through, where in the meltingly beautiful slow movements you can all but see the morning light playing on the water of the lagoon or feel the quiet awe and majesty of the dusky interior of one of the city’s churches. The allegros have a positive energy, carried along by bubbling counterpoint, that reminds us that Venice was a hub of life and activity, even during its period of relative decline in Albinoni’s day. For by the 18th century the previously powerful Serene Republic was deriving its livelihood mainly from tourism—particularly during the popular Carnival season preceding Lent.

Elegance, stability, and order—as well as a sense of pure, elemental joy—are the qualities I hear in Albinoni’s music. It is music of Venice through and through, where in the meltingly beautiful slow movements you can all but see the morning light playing on the water of the lagoon or feel the quiet awe and majesty of the dusky interior of one of the city’s churches. The allegros have a positive energy, carried along by bubbling counterpoint, that reminds us that Venice was a hub of life and activity, even during its period of relative decline in Albinoni’s day. For by the 18th century the previously powerful Serene Republic was deriving its livelihood mainly from tourism—particularly during the popular Carnival season preceding Lent.

You can also hear, in Albinoni, a connection to the Italian Renaissance tradition going straight back to Giovanni da Palestrina. Like the great church musician, Albinoni was a master of polyphony, of combining multiple musical lines (whether of voices or instruments) into a euphonious whole, and he continued this noble tradition into a final phase before it gave way to the new, simpler fashion for a single melody with accompaniment that would characterize the rococo and Classical eras. In his string sonatas, Albinoni’s violins sing a pure lyricism strongly rooted in the Italian tradition of the voice.

Perhaps you are thinking: what of Albinoni’s better-known contemporary, Antonio Vivaldi? Nobody would deny that Vivaldi was a bold talent and a brilliant innovator; his Four Seasons is a work of real genius. Yet, for me, Vivaldi’s glib facility does not always wear well over the long haul; Albinoni has greater heart and substance, and his more conservative and reserved nature results, to my taste, in more lasting musical values. An aristocrat of music, Albinoni could be considered the thinking man’s Italian Baroque composer. Of course, it was partly his being a man of means that allowed him to pursue this more thoughtful path. Since Albinoni did not need to churn out music to survive, what he published was bound to have a higher quality quotient.

No greater tribute to his talent could be found than the fact that the young J.S. Bach chose themes by Albinoni on which to base some of his fugues. A voracious reader of music, Bach obviously saw the worth in Albinoni (as he did also in Vivaldi and others), and the Italian fire and glow in the music allowed the great German genius to form his own unique musical synthesis. Perhaps it was just a case of one genius paying tribute to another.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

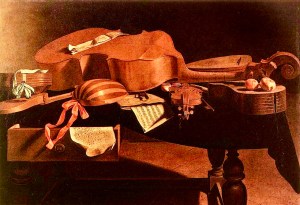

The featured image is “Musical instruments” (17th century) by Evaristo Baschenis, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. The anonymous painting of Tomaso Albinoni is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.