I LOVE rain. One of my greatest pleasures is to sit in our tiny conservatory while it batters down above my head, watching our stream rising (often very quickly). I even get a bit edgy when there are long dry spells.

Lucky for me, then, that we live in the Ribble Valley of Lancashire where it seems to rain more days than not. Actually I am not far out – according to the Met Office, in our nearby market town of Clitheroe there are 167 days a year with rain, which is only a few short of half. The average annual rainfall is 51 inches. The comparative London figures are 111 days with rain and 24 inches a year, and for Southend on Sea in Essex (God’s own city where we used to live) it is 102 rainy days and 21 inches a year. The wettest place in Britain (with a rainfall monitor) is Capel Curig in Snowdonia (or Eryri as we are now supposed to call it in honour of the decreasing number who speak Welsh as a first language, a number so small that I can’t find it recorded anywhere), where it rains 207 days a year and the total fall is 107 inches. Paradise!

We used to spend quite a lot of time in the Lake District and it always seemed to me that the rain there was wetter than anywhere else, with bigger drops closer together (which would explain why there are so many anorak shops in Ambleside). I can’t actually stand up that theory but I have found out a bit about raindrops.

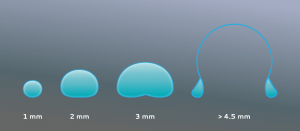

They are formed by water vapour condensing around microscopic particles of dust, salt, smoke or pollution and increase in size by merging with each other. When they are too heavy to continue to float in the cloud they fall to the ground. The tiniest drops are 0.5mm (0.02in) in diameter and these are what we call drizzle. The smallest raindrops are 1mm (0.04in) and are round (no raindrops are shaped like teardrops). At 2mm (0.08in) raindrops start to flatten as they fall against the air pressure. At 3mm (0.12in) depressions form on the bottom of the drops. At 4mm (0.16in) raindrops they distort into a parachute shape. At 4.5mm (0.18in) they split into two separate drops. So I am guessing that Lake District rain is just under 4.5mm.

Here is a diagram.

In my opinion Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head is one of the worst songs of all time and very nearly ruined Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, so I am not going to inflict that on you, but I thought readers might enjoy this vintage clip from the 1952 film Singin’ In The Rain, with maximum size raindrops. I suspect that as they will have been produced from a hosepipe they didn’t have time to split. I hope Gene Kelly didn’t have to do too many retakes.

***

A COUPLE of weeks ago I wrote about the woke townies who think, quite wrongly, that they know how to run the countryside. Yesterday’s Country Squire Magazine featured a terrific broadside from Gary Baxter, who lives and works in the countryside, which castigates several offenders including the BBC, the RSPB, Natural England, Chris Packham and his outfit Wild Justice, Natural Resources Wales, Brian May and Rishi Sunak. The language is more colourful than I dared use, and I thoroughly commend the piece which you can read here.

***

OUT with Teddy the labrador on the fells yesterday, Alan heard the first skylark of the year. I wrote about them here a few years ago for any readers who would like to visit or revisit the article.

***

Goat of the Week

THIS splendid fellow is a male Bagot, a member of probably the oldest goat breed in Britain and certainly the first to be documented. He is lucky to be around as the breed came within a whisker of extinction last century.

The legend is that when Richard the Lionheart returned to England from the Crusades in 1194, he brought with him a few black and white goats from Switzerland, which presumably were looked after at court. Two hundred years later, in 1380, his successor Richard II presented the herd to to Sir John Bagot of Blithfield Hall in Staffordshire, and the first written reference was made in 1389. Being hardy and self-reliant, they roamed freely in Sir John’s nearby 800 acres of woodland, Bagots Park, and provided sport for royal hunting parties. This was their home for 600 years. They were so important to the Bagots that they feature on the family coat of arms.

In 1953 most of the Blithfield estate was flooded for a new reservoir to serve Birmingham, and the remaining woodland was cleared for farming. Unlike other breeds, the Bagot goats had never been selectively bred to improve their meat or milk production so were not considered of any commercial importance. Most of the hundred or so animals were slaughtered, a few went to private farms and zoos, and 20 were kept near the Hall. They did not thrive in their comparatively small enclosure and by 1979 there were only 12 left; these were entrusted to the Rare Breeds Survival Trust. The Trust’s goal was rapid increase of numbers so the pure Bagots were crossed with similar breeds. But a handful of enthusiasts realised that the ancient bloodline was in danger of being lost, and they formed the Bagot Goat Breeders Study Group in 1987. They traced some of the relocated pure stock and compiled a breed register.

According to the Rare Breeds Goats website there are now an estimated 200 – 300 breeding females in Britain. Bagots may be familiar to a few readers because their main function today is as conservation grazers and browsers, and they are found at several locations around the country. Here is a video of a herd arriving at Cromer in Norfolk to undertake their annual task of clearing the cliffs of rampant vegetation including brambles.

It seems a shame but recently North Norfolk Council decided to retire the herd. (One of the reasons given is that the goats are ageing. Maybe the council don’t realise that they breed and thus replace themselves?) The goats are now working for the Norfolk Wildlife Trust at Cranwich Camp, a former Army site which the Trust is restoring.

There are four Bagots working with two Kashmiri goats in the Avon Gorge near Bristol.

There is a semi-feral herd at Levens Hall in Cumbria, and this is probably the nearest equivalent to the original herd at Bagots Park.

The breed is described as small to medium, with black forequarters and white on the rear part of the body. Some have a white blaze and/or black/white patches. Both sexes have long curved horns. They are said to be shy, but can be tamed.

You can find out more at the Bagot Goat Society website.

Here’s a delightful video of some Bagot kids.

***

Wheels of the Week

THIS IS a 1968 Austin 1800, 1798cc.

Launched in 1964 at a price of £828, the 1800 was developed by BMC as a larger follow-up to the successful Mini and Austin 1100. The Morris 1800 and Wolseley 18/85 variants followed in in 1966 and 1967 respectively.

With its unconventional low shape it was soon nicknamed ‘the landcrab’. It was roomy and had good roadholding and steering. However, according to Retro Motor website, owners soon discovered that ‘BMC had, once again, failed to finish the development process’. Faults included ‘failing engine mounts, scuffing front tyres, rattling steering racks and a gearlever that couldn’t resist a fight. Once you’d actually battled your way into first or second, the lever would often jump back out. Infuriation would be heightened by the Austin’s switchgear, which was so distant that when you were strapped in with static seatbelts, you couldn’t reach much of it. A distant under-dashboard handbrake and an awkwardly angled steering wheel made this supposedly luxurious saloon a physical battle to drive’. Probably the most notable problem was a dipstick which was incorrectly marked, leading owners to overfill the engine with oil. Rapid and unannounced modifications swiftly followed, reinforcing the impression that the 1800 had been launched too soon.

Astonishingly, BMC did not have a market research department, and so when dealers forecast that they would shift 4,000 1800s a week the firm took their word and tooled up to produce that number. In the event sales were under 800 a week.

A Mark II was launched in May 1968 (a month after the one in the picture was registered) and a Mark III in 1972.

By the time production ceased in 1975, when it was replaced by the Austin Princess, a total of 386,000 of all variants had been made. If you fancy one, here is a 1973 model for sale in Wigan with 68,000 miles on the clock and needing ‘light recommissioning’ for £4,995. The one in the picture sold for £4,400 in 2020.