The students of a classical education are part of nothing less than a civilizational renaissance, the revitalized intellectual tradition of a distinctive and vibrant Christian culture.

Patrick Henry College recently brought more honor to the exciting renewal of classical education nationwide. Not only has the small liberal-arts school in Purcellville, Virginia, won nine of the last twelve American Moot Court Association National Championships, but PHC just received international accolades as the first place winner in the 2016 Nelson Mandela World Human Rights Moot Court Competition in Geneva, Switzerland. As such, the debate team of rising juniors—William Bock and Helaina Hirsch—demonstrated the enduring legacy of the classical rhetoric tradition, even over the likes of Yale, Duke, and the University of Virginia.

Patrick Henry College recently brought more honor to the exciting renewal of classical education nationwide. Not only has the small liberal-arts school in Purcellville, Virginia, won nine of the last twelve American Moot Court Association National Championships, but PHC just received international accolades as the first place winner in the 2016 Nelson Mandela World Human Rights Moot Court Competition in Geneva, Switzerland. As such, the debate team of rising juniors—William Bock and Helaina Hirsch—demonstrated the enduring legacy of the classical rhetoric tradition, even over the likes of Yale, Duke, and the University of Virginia.

PHC’s achievements, though certainly impressive, are increasingly par for the course among classical schools. In secondary education, schools such as The Logos School and The Ambrose School, both in Idaho, have ranked as high as fifth in the nation in mock trial competition. The Logos School in particular has qualified for the national competition an astonishing fourteen times.

However, the recovery of rhetorical skill among classically-educated students is about far more than the mere accumulation of competitive laurels. Rhetoric was historically central to the formation of classical culture. As Patristic scholar Carol Harrison has noted, the various constituents of classical intellectual life—its educational system, its legal and political practices, its ceremonies, literature, and art—were all founded upon the art and practice of rhetoric.[1] On the one hand, the concern for rhetoric was certainly practical, in that rhetorical training fostered an educated elite of judges, senators, governors, and military leaders responsible for the welfare of the city-state. On the other hand, there was a cultural significance to rhetoric. Rooted as it was in the grand Homeric epics, rhetoric was envisioned as having immense power to shape the way people thought and behaved.

This is why the classical educational curriculum relied on rhetoric to shape a common culture or what the Greeks called paideia, which, once learned and mastered, identified its practitioners as part of an educated elite—those entrusted with maintaining the cultural life of the city-state. Because the literate all read the same books, poets, and histories, because they all studied the same music, art, and sport, they shared a common lifeworld, and were able to speak to each other and the rest of society as embodiments of what were considered humanity’s highest ideals.

The work of Patristic scholar Frances Young has detailed how this classical emphasis on rhetoric provided the foundation for the emergence of a distinctly Christian paideia or culture.[2] Young noted that the sacred Scriptures of early Christians provided the foundation of what she calls a “totalizing discourse.” In other words, the Christian meta-narrative from creation to consummation, from the first Adam to the new Adam, provided an alternative cosmic narrative to that offered by the classical world, by which the totality of life could be understood. The writings of the Christian apologists in the second century, and the schools that developed over the course of the third in Alexandria, Antioch, Caesarea in Palestine, Edessa in Syria, were all characterized by a classical curriculum that had been reoriented around the emergence of the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments.

Since the founding of the Logos School in 1994, there has been nothing less than a renaissance of classical Christian education through the U.S., Europe, and Africa. According to the Association of Classical Christian Schools membership statistics, there were ten classical schools in the nation in 1994; today there are more than 230. Since 2002, student enrollment in classical schools has more than doubled from 17,000 nationwide to more than 41,000, and all indicators suggest that the next decade will be one of significant growth. And we are already seeing the effects of this kind of education. As of 2015, classical schools had the highest SAT scores in each of the three categories of Reading, Math, and Writing among all independent, religious, and public schools.

However, could the recovery of classical education mean more than mock trial and SAT achievements?

Students are once again reading the classical texts and great books, reciting the same epic poetry, studying the classical languages, developing comparable music literacy, worshipping through traditional liturgy, and writing and orally defending theses. Through this renewed Christian paideia, they are rediscovering what it means to be truly human, particularly as our humanity has been restored in the redemptive work of Christ. In short, they are rediscovering the distinctively Christian conception of the educated person.

And so, the reemergence of classical education over the last few decades is doing far more than simply winning competitions and training our students to think; with trophies in hand, it appears that our students are part of nothing less than a civilizational renaissance, the revitalized intellectual tradition of a distinctive and vibrant Christian culture.

This essay was first published here in September 2016.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

[1] Carol Harrison, The Art of Listening in the Early Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 37.

[2] Frances Young, Biblical Exegesis and the Formation of Christian Culture (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997).

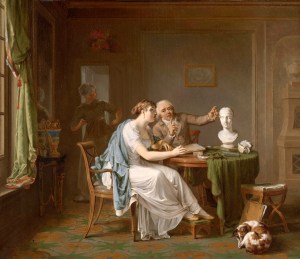

The featured image is “The Drawing Lesson” (c. 1810) by Louis Moritz, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.