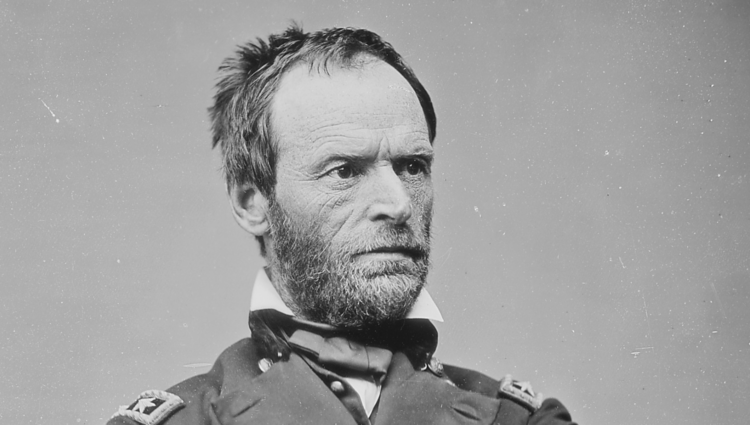

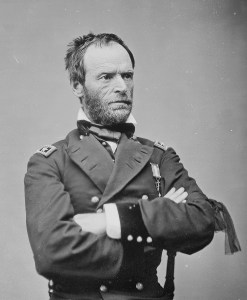

Our students read the greatest books of the tradition, a challenge to the brightest minds, and risk themselves repeatedly in conversation, until those who are seasoned “invariably deem it a special privilege to be in the front,” as General William Tecumseh Sherman said of veteran soldiers.

Years ago, when my wife and I taught at Thomas More College in New Hampshire, we came to know a couple from New Haven, Charles and Mary Alice O’Connor, through their gifted children, who were students and alumni of the college. Charles was a lawyer, witty and full of life, and he knew that I was from Georgia. He used to delight in pulling me aside, opening his wallet, and showing me the picture of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman that he kept inside it. He counted on my dismay, and I can hear his laugh now.

When I was growing up in Middle Georgia in the 1950s and 1960s, Sherman’s name glowed with infamy like a live coal raked up in the ashes. This was remarkable, because it had been a whole century since the broad columns of his army, encouraged to “forage liberally,” left a path of destruction through the defenseless civilian population of Georgia in the late fall and early winter of 1864—charred wood where houses had been, bitter women, a landscape stripped of anything the foragers could find to appropriate or eat, a spirit of desolation. Sherman’s deliberate policy of destruction helped shorten the Civil War, but it left a lasting resentment in the South. Coming to terms with Sherman has been a challenge for many Southerners, including me. Since I stepped down from the presidency of Wyoming Catholic College back in August, my major writing efforts have been directed toward finishing my third novel, which will deal in part with Charles O’Connor’s favorite. Now that I am on sabbatical for the semester, the engagement with Sherman has intensified, for good or ill.

Reading a number of biographies and histories of the Civil War in the West, Sherman’s journals, his exchange of letters with his wife, and his Memoirs, first published in 1875, has unquestionably given me a deeper understanding of Sherman’s brilliance and boldness. He was a man of omnivorous interests and considerable learning, a lover of art and opera, as ardent an admirer of Shakespeare as Lincoln, an early master of modern logistics (a “born quartermaster,” as one of his superiors said), and a brilliant strategist.

But despite leading to greater sympathy (especially with his personal trials, such as the loss of his beloved son Willie to typhoid fever), my immersion in his life has not put to rest old questions about his advocacy of total war as the only means for crushing the Confederacy and reconstituting the Union. In a letter to Gen. Halleck after the fall of Vicksburg, Sherman asserted “the broad doctrine that as a nation the United States has the right, and also the physical power, to penetrate to every part of our national domain, and that we will do it … that we will remove and destroy every obstacle, if need be, take every life, every acre of land, every particle of property, everything that to us seems proper; that we will not cease till the end is attained.”

It is difficult to say exactly what vision of America this policy of force finally serves. Sherman hated politics, and his cause was never the abolition of slavery, as his biographers unanimously agree. Those looking at the March to the Sea or the immolation of Columbia, South Carolina, in February of 1865 (see Charles Royster’s The Destructive War) might accurately see in these modes of war a shadowy preface of World War II, including the Blitz in England and Curtis Lemay’s firebombing of Tokyo—not to mention Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In important ways, Sherman increasingly came to embody what Machiavelli calls the “effectual truth” that cuts through sentiment and illusions of nobility. “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it,” he famously wrote to the mayor of Atlanta in refusing his pleas for Sherman not to exile civilians from Atlanta.

Meanwhile, as I think about Sherman, I witness daily the ongoing work of Wyoming Catholic College. Should this man, whose statue has never been toppled or melted down and whose picture made it into the wallet of a man I admired, be a model for our students at Wyoming Catholic College? Not as a religious example, certainly. I have not mentioned Sherman’s lifelong resistance to the Catholicism practiced by his devout wife or his fury that a son became a priest (another story). But one passage toward the end of Sherman’s Memoirs rings wholly true for Wyoming Catholic, because it echoes Aristotle’s understanding of happiness as activity in accordance with the highest virtue.

In “Military Lessons from the War,” Sherman expresses his concern that generals in the field might be hampered or constrained by politicians remote from the actual circumstances. Battle should be the responsibility of the leader actually present. He writes almost lyrically about it. “To be at the head of a strong column of troops, in the execution of some task that requires brain, is the highest pleasure of war–a grim one and terrible, but which leaves on the mind and memory the strongest mark; to detect the weak point of an enemy’s line; to break through with vehemence and thus lead to victory; or to discover some key-point and hold it with tenacity; or to do some other distinct act which is afterward recognized as the real cause of success. These all become matters that are never forgotten.”

Everything at Wyoming Catholic College pushes students toward responsibility and engagement in the front, certainly their outdoor leadership, but also their classes and public performances. Sherman’s description of the “highest pleasure of war” reminds me, at least in its intensity, of our seniors giving their orations several weeks ago literally in front of the room, fully engaged, answering questions, in the execution of a task that “requires brain.” Our students read the greatest books of the tradition, a challenge to the brightest minds, and risk themselves repeatedly in conversation, until those who are seasoned “invariably deem it a special privilege to be in the front,” as Sherman says of veteran soldiers.

But the world is full of effectual truth these days, and my great hope is that Wyoming Catholic College graduates will bring something besides cruelty and harshness to the front: “the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and of the fear of the Lord.” I am confident that this education will give them a moral and spiritual habitus that prepares them for boldness and command in the battles yet to come for the nation and the Church.

Republished with gracious permission from Wyoming Catholic College‘s weekly newsletter.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a photograph of William Tecumseh Sherman, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.