YESTERDAY’S Budget misses the point. The wrong question is answered. Tax cuts are super, modest as they are in the context of recent rises and should help at the margin, but the real question of how the UK re-creates its long-lost private sector dynamism requires a much more holistic and longer-term answer, rather than Jeremy Hunt’s lame, micro-management measures. This was missing, and is also missing from Labour, the likely (if only by default) beneficiaries of this self-inflicted decline.

This was a poor and delusional show and underlines why Britain remains in dire trouble. Divided, devoid of any growth or much hope, with short-term political fixes generally centralising and distorting market approaches hollowing out the longer-term potential, this Budget does not move the dial.

The only thing going for the UK is that its corporate assets are cheap by global standards. But they are cheap for a reason. The good ones will be and are being acquired. For the rest, without a radical new approach, it is death by a thousand cuts. It’s fashionable to recommend an overweight in the UK on valuation grounds. Fair enough, but structurally, without a change of direction, longer-term Britain is a big sell.

The UK should have extraordinary strategic advantage. It is the home of the English language, arguably the most important city on the planet, one of the world’s two top financial centres, elite education, sport and unrivalled cultural assets, with many other leading centres of excellence.

More, we are living through an extraordinary technological revolution which in many sectors, although not the public ones, is manifestly improving productivity. Critically, too, the UK is (or was) considered to be stable, enjoying the rule of law which over centuries of turbulence elsewhere stood out. That was then.

So why is the UK performing so poorly?

The problem has been at least 25 years in the making, exacerbated for sure by very poor policy choices over the last five years. Simply put, the UK has moved from a broadly free market economy 25 years ago to a highly managed state- and regulation-driven one today.

In 1997 the state accounted for about one third of the economy. Today it’s almost half. This in itself underestimates the problem as regulation particularly in financial services, energy, employment law and the like has increased exponentially, further undermining market responses. The UK is a post-free market economy. It is now statist, centralised and controlled, and with it opportunity has withered.

As a result of this shift, which is not addressed at all by yesterday’s Budget, the UK has become an ex-growth economy and one driven more by keeping close to the regulator or government, rather than by free enterprise.

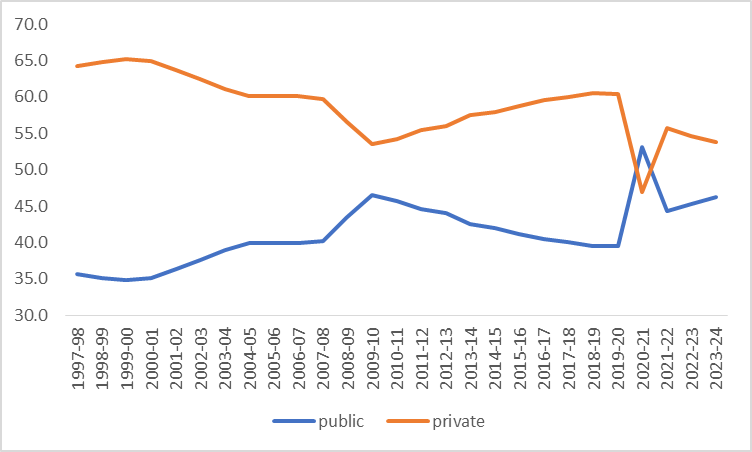

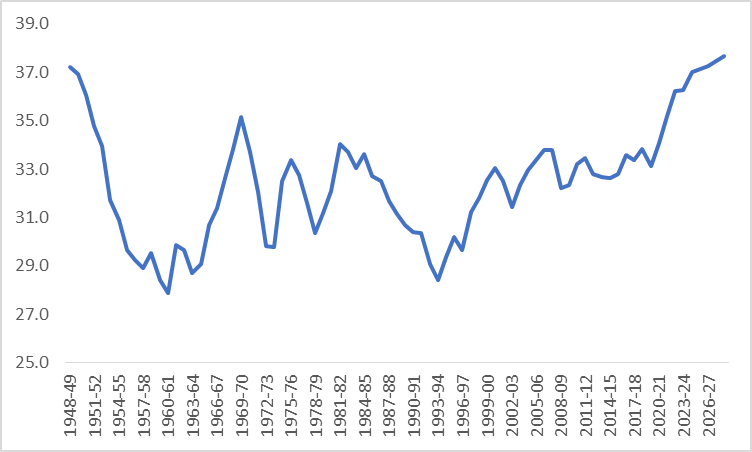

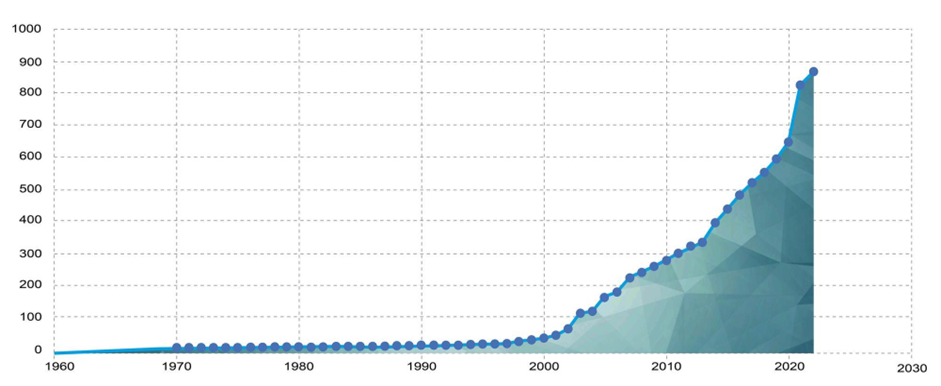

The three key charts highlighting the UK’s transition from a broadly free market economy to a centralised statist one are highlighted below, namely examining growth in public spending, tax and regulation. Perhaps the last of the three charts, on regulation, is the most extraordinary of all. In effect the private sector’s decline mirrors public sector growth, with the latter crowding out the former and with it greatly undermining long-term growth potential.

UK public and implied private spending to GDP

UK tax to GDP

Cumulative ESG (environment, society, and corporate governance) policy interventions

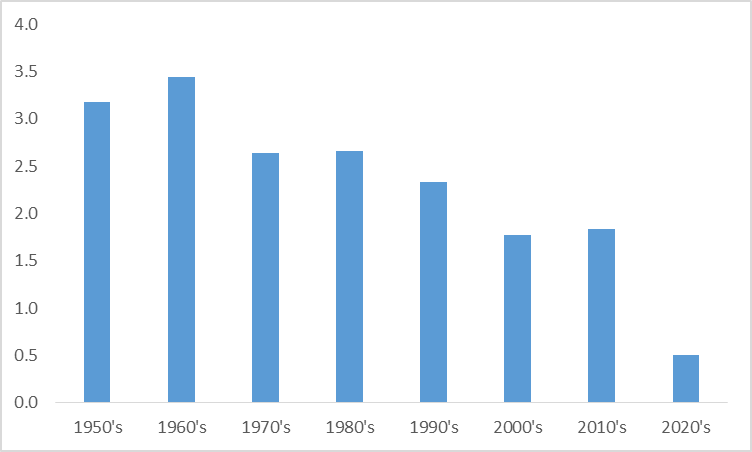

We would argue as a result of these policy choices growth has withered as outlined by the chart below which examines average annual growth per decade. It will be observed that growth is in structural decline.

UK GDP growth by decade %

The above chart substantively overestimates GDP growth as it is a whole economy measure. With the population growing rapidly over the last 20 years from previous near-stability as a result of an effectively open borders policy, the more important measure is on a per capita basis (per head of population) and as can be seen from the chart below on this measure GDP is back to 2018 levels.

This stagnant performance is unprecedented and as far as we are aware is the weakest compound performance over six years in modern times i.e. over the last two hundred plus years.

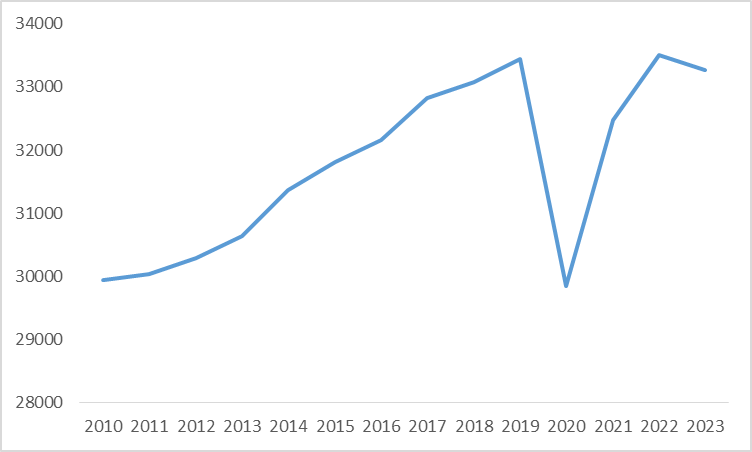

UK GDP per capita 2010 to current

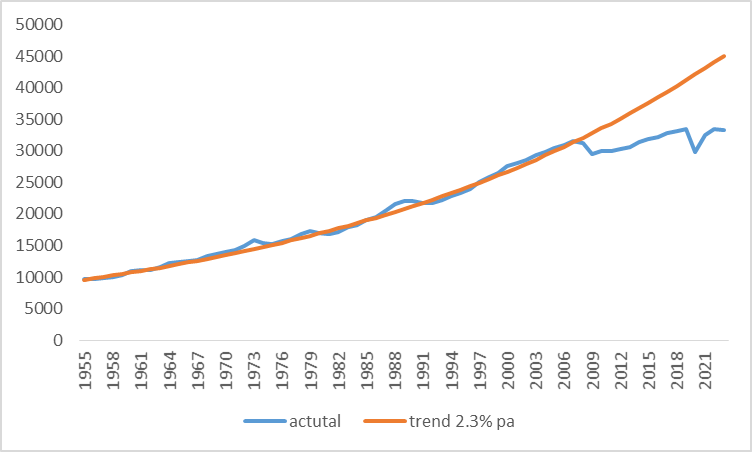

To put the scale of this failure in context, from 1955 to 2010 per capita GDP growth averaged a very consistent 2.3 per cent. Today, according to the ONS, per capita GDP stands at £33,271. If the long-term trend growth had continued since 2010, current per capita GDP would be some 35 per cent higher at £45,062. That is a staggering underperformance.

UK GDP per capita 1955 to date with trend growth of 2.3% from 1955-2010

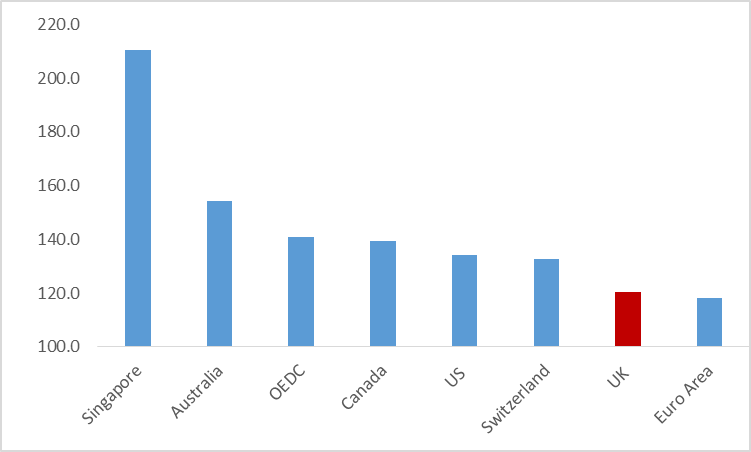

For those who think this is a developed economy phenomenon, think again. It’s a British and European problem. Other advanced economies, notably the US, Australia, Canada and the OECD, have all done markedly better, performing not far off the UK growth average of between 1955-2010. This is outlined in the chart below. Decline is not inevitable. It’s a consequence of very poor policy choice.

Major developed nation GDP growth indexed to 2022 2005=100

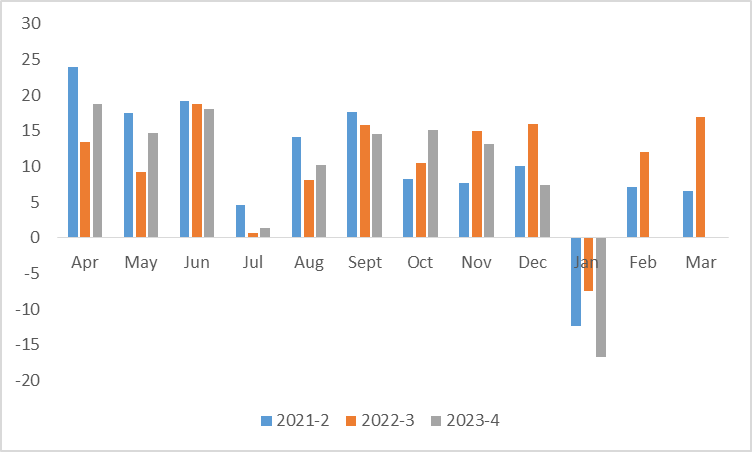

Yesterday’s Budget misses the point. The point is that spending and regulation is out of control and this is crowding out the private sector. Since 2017-8 spending in real terms has increased by a staggering £179billion or by 21 per cent from the base year. This is unprecedented in peace time and despite this, judging by polling evidence, public satisfaction with public services is, to put it mildly, poor.

UK Total Managed Expenditure 2017-8, real TME since 2017-9 and real spending increase (RHS) £bn

This is a very concerning square as while we suspect the likely next Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, will be constrained by an already very highly taxed and indebted economy with poor public sector outcomes, the structural impediments to change are large: quangocracy, legal, diseconomies of scale, public sector quasi-monopolies, unions, media response etc. The system embeds and arguably rewards failure.

Public dissatisfaction is high but unfocused. Some believe (extraordinarily) that there has been austerity, others draw different conclusions. Most agree there is a major problem, but the mood is volatile which in itself risks poor policy response.

Rachel Reeves will need to be very careful. The tax burden is met by a tiny pool of people, many of whom may be mobile (top 1 per cent pay 27 per cent of income tax, and according to HMRC of the three million corporations filing a tax return only 57,000 file a profit of over £100k; just 4,255 companies reported a profit of over £1million).

The tax base is thus very narrow, yet the people desire much, often without reference to either their enterprise or its cost. Without clear leadership, which currently seems lacking, these are exceptionally unstable times, but taxing more risks capital flight and would likely be highly counter-productive.

And despite the record tax take the fiscal deficit remains dangerously embedded. £96.6billion borrowed year to date, broadly the same as last year’s £99.9billion at the same stage, and a likely annual deficit of some £120billion, or almost £5,000 a household. This leaves almost no headroom for shocks which in a world of uncomfortable war sabre-rattling, energy shocks and technical recession is a very uncomfortable square indeed.

UK GDP growth by decade %

The reality is unless forced by market imperative the UK is locked into a tax and spend culture. If 14 years of Conservative rule have embedded this culture what chance of a change under Labour? More so, as now over half the population receive more in benefits than they pay in. The current debate is depressing dominated by consensus of tax, spend, regulate and centralise.

Worse, the population are fractious, confused and upset, not just for economic reasons. The country’s problems materially transcend mere economics. This will likely be a turbulent period for both the UK economy and politics.

While it would be relatively easy to turn this failing ship round with supply side reforms, normalised public spending recycled into tax simplification and cuts, regulatory advantage rather than the current Regulation Central, and a migration policy which was balanced and not destructive to either wages, services or housing affordability, in this political environment such an approach is in the medium-term highly unlikely.

Until Government trusts the people and supports families rather than seeking to control them, it is hard to see a happy ending especially as the state appears mired in the management of decline.