The narrative of a North-South divide in American History is a powerful, yet problematic one. However, closer metaphysical inspection of both regions uncovers a series of considerable similarities and ironic connections between the Puritans of New England fully embodied in Jonathan Edwards, and the Presbyterians of the Old South fully embodied in James Thornwell. Their metaphysical systems, separated by just a few generations, contained utterly similar orthodox Christian commitments and inspired similar acts of protest and rebellion. Furthermore, despite Christianity’s implications for justice, both groups struggled to consistently apply that ethic with groups determined to be “others.” Yet the regions where these parallel worldviews took root would part ways in the growing regional conflict that culminated in Civil War. A closer look at these two foundational theologians can help bridge the yawning historical and rhetorical chasm between North and South. Drawing these parallels counteracts the platitudes inherent in the North-South narrative, and brings about a deeper understanding of American history, human nature, and ourselves.

The narrative of a North-South divide in American History is a powerful, yet problematic one. However, closer metaphysical inspection of both regions uncovers a series of considerable similarities and ironic connections between the Puritans of New England fully embodied in Jonathan Edwards, and the Presbyterians of the Old South fully embodied in James Thornwell. Their metaphysical systems, separated by just a few generations, contained utterly similar orthodox Christian commitments and inspired similar acts of protest and rebellion. Furthermore, despite Christianity’s implications for justice, both groups struggled to consistently apply that ethic with groups determined to be “others.” Yet the regions where these parallel worldviews took root would part ways in the growing regional conflict that culminated in Civil War. A closer look at these two foundational theologians can help bridge the yawning historical and rhetorical chasm between North and South. Drawing these parallels counteracts the platitudes inherent in the North-South narrative, and brings about a deeper understanding of American history, human nature, and ourselves.

Clearing the Rubble: Overcoming Cultural Baggage Associated with Puritans and Southerners

The barrier to such a comparison is that in the current cultural milieu, New England Puritans and Old South Presbyterians are the quintessential bigots. Their view of the world was patriarchal, hierarchical, and based on the exclusive truth claims of Christianity, and just as in baseball, so too in popular culture today: three strikes and you’re out. Perhaps no groups in American history are more vilified than the Puritans who destroyed Native American tribes and hunted for witches, and Southern Presbyterians who enslaved Africans and seceded from the United States. These questionable applications of their metaphysic usually results in a de facto dismissal of anything else valuable they might have to offer.

But this approach turns history into a giant blame game whose only purpose is to decree posthumous guilt trips on descendants of the offending parties or pat ourselves on the back for supposed progress. As French historian Jacques Barzun said in his summa, From Dawn to Decadence, “history is not an agency nor does it harbor a hidden power; the word history is an abstraction for the totality of human deeds, and to make their clashing outcomes the fulfillment of some concealed purpose is to make human beings into puppets.”[1] The complexities of causation, human choices, environmental factors and social conditions remind us that history is a human story that deserves more than simple truisms that turn historical figures into ideological winners and losers.

The surface critiques of New England Puritans and Southern Presbyterians overlook such complexities and miss out on their great insights. Noteworthy scholars Perry Miller and Edmund Morgan helped recover a full-orbed Puritanism with their meaningful family practices, connected communities, and educational solutions. Similarly, Richard Weaver and the Southern Agrarians rightly restored credibility to the worldview of the Old South and the value of family, place, and valid forms of hierarchy and distinction. However, what remains largely untouched are the areas where these two systems overlap. What will be further developed here are the substantial connections between the New England Puritan and Southern Presbyterian worldviews, which transcend the North-South paradigm and come round about to Socrates’ perennial advice to “know thyself.”

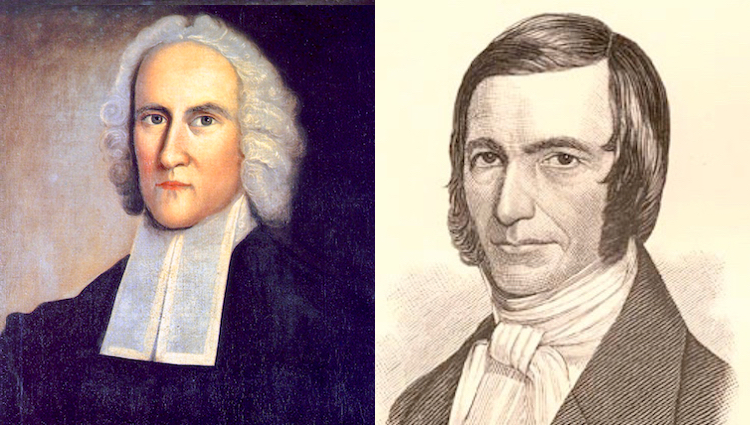

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758): Puritan Defender of Orthodoxy in the age of Enlightenment

In 1703, Jonathan Edwards was born in rural New England into a rich theological heritage built by his well-respected grandfather and pastor, Solomon Stoddard. In this environment, he took to education quickly and at thirteen attended Yale where he graduated first in his class four years later in 1720. His marriage to Sarah Pierrepoint in 1727 began what Edwards called an uncommon union, blessed with several children.

While a pastor in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Edwards’ preaching contributed to what became known as the First Great Awakening. As George Whitefield came to America, the movement took on a national character in the 1730s and 1740s as Edwards, Whitefield, and Charles and John Wesley played central roles in guiding this new movement. It was during the course of the Awakening that Edwards preached his widely anthologized sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” delivered not with emotionalism and excessive gestures, but with heart-felt emotion and a tear in his eye. Edwards believed that there was inherent power in the Word preached, not in the style in which it was preached.[2] This view made Edwards the Awakening’s greatest critic and supporter. He wrote several treatises on the Awakening, most notably The Religious Affections, which addressed how to distinguish between authentic and spurious religious experience. This issue was so controversial during the Awakening that it split Puritanism into Old Light and New Light varieties.[3]

Edwards’ life as preacher and writer brought him into many conflicts, and ultimately led to dismissal from his congregation in 1749 over who to admit to the Lord’s Supper. He spent the latter portion of his life as a missionary to the Mohawk Indians, and then as President of The College of New Jersey, now Princeton University.[4] In 1758, his life came to an abrupt end when he died from a small pox inoculation at the age of fifty-four, but time has proven his worth not only in theology but also philosophy. As William Frankena states, “[it] is now increasingly realized, he was perhaps the outstanding American philosopher to write before the great period of Price, James, Royce, Dewey, and Santayana.”[5]

Edwards’ able defense of orthodox Christianity in the Age of Enlightenment has also stood the test of time, and has solidified his place at the pinnacle of New England Puritan orthodoxy in the 18th century.[6] Being conversant with Enlightenment thinking, Edwards used these new concepts in such a way that the precise thought-patterns that were on track to dethrone Christianity in the Western World were the exact weapons he wielded to defend historic orthodoxy.

As a defender of the historic faith, Edwards now took the initiative to turn the tables on the religion of the Enlightenment. . . . Deists had to answer to the work of God in history, supremely in the person and work of Jesus of Nazareth. . . . He . . .[provided] a calculated point-by-point response that, as a whole conveyed a holistic Christian worldview about reality. . . . Now the enemy was deism, and the task for Edwards was to expose it for the great evil and apostasy that it was, and eradicate its presence from the halls of faith.[7]

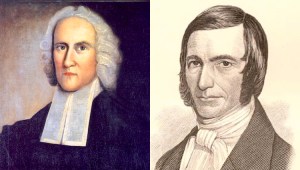

James Thornwell (1812-1862): Presbyterian Defender of Orthodoxy in the Age of Change

James Thornwell was born in poverty and obscurity in rural South Carolina, yet a few wealthy residents in the town of Cheraw noted Thornwell’s intellect and funded his education. As a budding student, Thornwell happened upon a copy of the Puritan Reformers’ Westminster Confession of Faith, which he devoured and soon joined Concord Presbyterian Church via profession of faith.[8] This set him on a path towards the ministry, graduating from South Carolina College with highest honors and going on to Harvard, only to be turned off by the lack of orthodoxy there.[9] He eventually was ordained as a Presbyterian minister and garnered an impeccable reputation for logical reasoning and sound theology, and soon ascended to the honored place of theologian par excellence of the South.

Thornwell’s career took him through several pastorates in the upstate of South Carolina in small towns like Lancaster and Waxhaw, to the presidency of South Carolina College, and the pastorate of historic First Presbyterian Church in Columbia, SC.[10] Throughout his career, Thornwell consistently upheld the Bible as God’s revelation and source of truth, and the ultimate basis for an all-encompassing worldview. This informed his critiques of the Second Great Awakening with its shift towards revivalism and Arminianism, which placed Thornwell firmly in the orthodox Old School camp, in opposition to the New School Presbyterians who supported revivalism and more latitude within Presbyterian theology and practice.[11]

Thornwell melded the Enlightenment ideals of science and rationality with orthodox Christianity by synthesizing his Old School Presbyterianism and Southern values with the latest incarnations of science in Baconian methodology and of rationality in Scottish Common Sense philosophy.[12] In the words of a personal friend, “he combined with his conservatism a striking originality, an almost daring theological initiative.”[13] The emerging theory of evolution with its materialist assumptions about the world was especially problematic, and Thornwell connected these issues with the growing disconnection from God, family, and land in the northern industrial, urban way of life. In perhaps his most oft-quoted words:

It is not the narrow question of Abolitionism or Slavery—not simply whether we shall emancipate our negroes or not; the real question is the relations of man to society, of States to the individual, and of the individual to States—a question as broad as the human race. These are the mighty questions which are shaking thrones to their centres, upheaving the masses like an earthquake, and rocking the solid pillars of this Union. The parties in this conflict are not merely Abolitionists and Slaveholders—they are Atheists, Socialists, Communists, Red Republicans, Jacobins, on the one side, and the friends of order and regulated freedom on the other. In one word, the world is the battle ground—Christianity and Atheism the combatants; and the progress of humanity the stake.[14]

For Thornwell, the ultimate issue was between the Northern materialist worldview and the Southern Christian worldview. This would become known as the “theological war” thesis; the Civil War as a battle of metaphysical systems. This was indeed a synthesis of mythic proportions; an internally coherent worldview that justified and explained Southern society, and defended it against the rapid changes occurring elsewhere in America, and throughout the world at that time. Far from popular opinion of the antebellum South as a backward society whose main goal was to ignorantly uphold the institution of slavery, Thornwell represents the breed of intellectuals who thought long and hard about these issues, and created nuanced and complex solutions to the problems facing the South. In Thornwell, one finds the full flowering of Southern conservative thought, and the foundations for the worldview of the Old South. As James Farmer writes in his masterful work on Thornwell, “the theological facet of Southern thought . . . played a leading role in the battle of the minds that preceded the battle of bullets.”[15]

Synthesis: Transcending the North-South Divide

Theological Conservatism

Although separated by about a century, Edwards and Thornwell transcend the standard North-South division so prevalent in many a history book and many Americans’ minds. On the religious front, the connections between their worldviews are hard to miss, as both Edwards and Thornwell shared an orthodox Calvinism with a high view of Scripture and God’s sovereignty, as summarized in the Westminster Confession of Faith that they both prized. Both encountered religious revivals during their lives, and while Edwards was integral in the First Great Awakening, he was critical of its excesses in a similar way that Thornwell was of the Second. Both embraced Christianity’s rigorous intellectual traditions as evidenced by their time as university Presidents and their prolific writings. But these were not stodgy theologians; they had a zest for life and an experiential piety that In Edwards’ day was called the combination of “light and heat,” while in Thornwell’s day, “logic on fire.”[16]

Both articulated compelling defenses of historic Christian doctrine against rising secular theories and utilized philosophical, historical, and biblical arguments to do so. Edwards’ defense of Christianity against deism was vital in Princeton Seminary’s emergence as a pillar of orthodoxy as “students were expected to be familiar with the ‘Deistical controversy’ and its principal sources and arguments, and well-armed to rebut them with Scripture and Confession.”[17] Edwards’ theological offspring are not the Unitarians of Harvard and Yale, but the Old School Presbyterians of Princeton, where he planted seeds as president. This places Edwards and Thornwell as theological-next-of-kin, as the same Old School Princetonians who trace their doctrinal roots back to Edwards, were closely allied with Thornwell on nearly all of the theological issues of the 19th century.

This point is important to note, especially in the years after the Civil War as Thornwell’s “theological war” thesis gained traction in some camps, including with Southern Agrarians.[18] While elements of the “theological war” thesis are attractive and help capture the growing cultural divide in the country at that time, it does not fully account for the theological diversity of both regions. Thornwell’s rhetorical flourish certainly had its intended effect, but it oversimplifies the North into a hegemonic Unitarian universe, neglecting to account for the orthodox Christians in the North, and presents the South as a unified Christian civilization, ignoring the heterodox Christians and the non-religious in the South.

What especially gets overlooked is the fact that some Southerners went North to Princeton University for theological training[19] because it was “the foremost intellectual center of Old School Presbyterianism.”[20] The theology that Thornwell defended against rising secular materialism—which he conflated with the North—was the same theology being upheld in the North at Princeton Seminary, and that Edwards defended years before when “materialism was rampant in New England.”[21] Thornwell himself found common cause with many of the Princetonians, something that gets lost in the case for a theological war.

There is certainly usefulness in the “theological war” thesis, as Richard Weaver picks up in his view of the Old South as “the last non-materialist civilization in the Western World.”[22] Much can be learned from the Old South, and Weaver’s essay “What Can the Southern Tradition Teach Us?” provides manifold lessons in that regard. But Weaver’s extensive knowledge of the Old South also caused him to acknowledge the significant Southern tradition of “non-creedal faith” due to the wide influence of the Anglican/Episcopal church.[23] This creates another layer of complexity as the “non-creedal” Southern tradition was on a path towards the same liberal theology that Thornwell decried as Northern. Perhaps a way forward is found in seeing that both regions provide a needed counter-balance to the blind spots of the other, similar to C.S. Lewis reasoning for reading old books and new books: “two heads are better than one, not because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the same direction.”[24]

Political Revolution

Politically there is a striking irony inherent in these groups’ actions and beliefs, for on the one hand they defended their traditional Christian beliefs against the Enlightenment, but on the other hand, they rebelled against authority and fought for individual freedom, which were Enlightenment ideals to the core. Puritan and Presbyterian church polity gave a prominent voice to individual congregants and local congregations, training their members to actively participate in political matters which was vital in the conflicts of their respective eras. It was New England Puritans whose metaphysic justified their previous rebellions against government in England, escape to America, and the remnants of which created patterns of behavior that resurfaced in the Revolutionary War.[25] President Calvin Coolidge made the connection to Edwards in this regard explicit: “the profound philosophy which Jonathan Edwards applied to theology . . . had aroused the thought and stirred the people of the colonies in preparation for this great event.”[26] In like fashion, Southern Presbyterians figured prominently in the Southern theater of the Revolutionary War, arguing for rebellion from their pulpits and fighting on the battlefield.[27] As the national crisis grew in the 1800s, Old South Presbyterians continued in this tradition justifying their state nullification of federal laws and secession from the United States in the Civil War with eerily similar lines of argumentation regarding independence and social contract theory.[28]

Social Order

In the social realm, Edwards and Thornwell saw an inherent logic and beauty to the created order that informed their understanding of family and society. This hierarchy, properly understood as one of roles, not of value, created meaningful, working models of community. However, such concepts of ordered freedom can also be misused, as evident in the complicity of New England Puritans in the subjugation of Native Americans and Old School Presbyterians in the enslavement of African Americans. This can be massaged somewhat by distinguishing between figures like Edwards and Thornwell who exemplified a sort of Christian paternalism versus those who made no such efforts at evangelization or humane treatment.[29] Interestingly enough, Edwards the New Englander, defended his ownership of slaves by arguing “the Bible explicitly allowed slavery, the New Testament doesn’t repeal slavery, and the Bible isn’t self-contradictory.”[30] This is the same argumentation Thornwell used in the mid-1800s while playing a central role in the growing slavery debate within Presbyterianism at the national level. He argued that since the Bible never explicitly forbid slavery, neither should the Church: “when the Scriptures are silent, she must be silent too.”[31] David Calhoun summarizes,

Thornwell saw slavery as part of the curse sin had introduced into the world—like poverty, sickness, disease, and death. . . . The South Carolinian defended slavery as “domestic and patriarchal” and opposed the reopening of the slave trade. He continually criticized the mistreatment of slaves and demanded the legal sanction of slave marriages, repeal of the laws against slave literacy, and effective measures to punish cruel masters. Furthermore, Thornwell strongly held to the unity of the races and repudiated the idea that the curse on Ham in Genesis was fulfilled by the infliction of slavery on the Africans.[32]

Despite efforts to ease such realities by calling these leaders “men of their times,” this overlooks the fact that there were other orthodox Christian “men of their time” that were utterly opposed to slavery. Furthermore, using the “men of their times” argument introduces a sort of back-door historical and chronological cultural relativism, undercutting the very concepts of timeless universal truth and morality to begin with. Consider Edwards’ Great Awakening contemporary John Wesley,[33] or Thornwell’s orthodox Calvinist contemporary John Williamson Nevin,[34] both of whom openly opposed chattel slavery. Perhaps even more stunning is the exegetical skill exercised by an unlikely Southern contemporary of Thornwell, who challenged the ostensible Biblical foundations of the pro-slavery argument. This was Angelina Grimke from a slave-owning family, who through careful analysis, attacked the Southern Apologists’ claim head on and argued that “American slavery as such didn’t exist in the Bible; that it would, in fact, be slanderous to claim biblical support for that institution.”[35] This was a bold strategy to engage on the clergy’s turf, and a strategy that John Wesley years before tended to avoid in his public arguments against slavery which focused more on “natural law and liberty.”[36] Grimke’s 1836 Appeal to the Christian Women of the South developed a point by point comparison of “Jewish servitude and American slavery.”[37] Increasing historical knowledge of the ancient Biblical world since Grimke’s day reinforces her argument:

there is no likeness in the two systems; I ask you rather to mark the contrast. The laws of Moses protected servants in their rights as men and women, guarded them from oppression and defended them from wrong. The Code Noir of the South robs the slave of all his rights as a man, reduces him to a chattel personal, and defends the master in the exercise of the most unnatural and unwarrantable power over his slave. They each bear the impress of the hand which formed them. The attributes of justice and mercy are shadowed out in the Hebrew code; those of injustice and cruelty, in the Code Noir of America.[38]

Conclusion: “Know Thyself” and the Power of Metaphysics

The counterbalance of Wesley, Nevin, and Grimke require us to let the uncomfortable reality remain. And we must let this tension remain, for if not, we turn a blind eye to evil, and the evil within ourselves. Edwards and Thornwell made a fatal mistake in their understanding of the Bible and slavery, one that just so happened to conveniently justify their current behavior.[39] The famed Old School Princeton Theologian Charles Hodge argued this exact point “when he said that Thornwell was using the spirituality of the church as a cover for his errors.”[40] This reality does not require us to dismiss the rest of their worldviews, but reminds us of their humanity, and ours. We see great glimpses of Christianity in its fullness in both Edwards and Thornwell, but also deep failures. Self-interest and self-deception run deeper than we’d like to think, and this temptation spans both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line, beyond that into all of time and place, yea, even into the hidden corners of our own hearts. This is perhaps no better encapsulated than in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s convicting insight from behind GULAG barbed wire:

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart? During the life of any heart this line keeps changing place; sometimes it is squeezed one way by exuberant evil and sometimes it shifts to allow enough space for good to flourish. One and the same human being is, at various ages, under various circumstances, a totally different human being. At times he is close to being a devil, at times to sainthood. But his name doesn’t change, and to that name we ascribe the whole lot, good and evil. Socrates taught us: Know thyself![41]

The depths to which Solzhenitsyn witnessed human depravity, corruption, and evil in the GULAG led him to such potent conclusions and provides hard evidence of original sin and the fallenness of humanity. This brokenness is not a Northern problem nor Southern problem; white problem nor black problem; it is a human one. Yet even more relevant to the issues at hand in this essay are the similar reflections of Albert Morgan, former Republican state senator and then sheriff in Mississippi during Reconstruction who was deposed from office in a coup of sorts.[42] His stinging insight into this human self-interest problem in relation to race and slavery, always stuns me.

The immortal few who dared to oppose slavery left their work less than half done. I write as a man for whom practical politics has utterly failed & who now in my later years is seeking to salvage some meaning for all I had been through. I have grasped at and sensed a hope of spiritual revolution for all mankind, but now I feel that the evils I had fought in Mississippi had roots far deeper in the soul of man than the question of race alone; they came at heart from the greed that makes men exploit others for their own gain. The negroes’ color & physical peculiarities make it easier to defend encroachments upon his inherent right to life, liberty & the pursuit of happiness. In this fact we find the mirror of our own souls, and show the full measure of our own baseness when we put the blame on God.[43]

Morgan is on to something here—the issue goes deeper than race into the human condition itself, and the temptation to find convenient excuse in anything, racial theories included, in the pursuit of self-interest. He argues that claiming religious authority for such justification provides the clearest evidence of the self-deception that runs deep into humanity’s core.

In the years since the giants Edwards and Thornwell walked the earth, evidence still clearly shows a broken world, and in this simple fact we find the great unity of the human race, grounded in a shared metaphysic, without which divisions drive even deeper. Weaver argued the same: “the challenge is to save the human spirit by re-creating a non-materialist society. Only this can rescue us from a future of nihilism, urged on by the demoniacal force of technology and by our own moral defeatism.”[44] What most transcends the North-South divide, and any divide for that matter, is the ideational reality of a shared human narrative, lived out in the shared human experience of fallenness and the common desire for redemption. It is here we find our need for each other, and for the One who came into the flesh, overcoming death to reverse the fall by the power of his indestructible life. In one another we find a true counterbalance to our own blind spots and find empathy in our shared experiences of human frailty and suffering, and in Christ we find the true solution to these deepest human groanings for restoration. Which brings us full circle, back to the old Puritan alphabet rhymes that both Edwards and Thornwell held so dear, and that encapsulate the core non-materialist foundation for their worldviews: “In Adam’s Fall, we sinned all . . . Christ crucified, for sinners died.”[45] After all, Edwards and Thornwell both certainly agreed on that doctrine.

This essay was first published here in May 2020.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence (New York: Harper Perennial, 2001), 654.

[2] Jonathan Edwards, Edwards on Revivals (Massachusetts: Dunning and Spalding, 1832), 233.

[3] Edwards is hard to fully categorize in either camp. His critics categorized him as a “New Light,” but doctrinally he was of “Old Light” persuasion. He also defies easy categorization because he himself was critical of the excesses of the movement he participated in. See Collin Hansen, “Revival Defined and Defended: How the New Lights Tried and Failed to Use Religious Periodicals to Quiet Critics and Quell Radicals,” Themelios, 39, no. 1 (2014): 29-36.pdf .

[4] “Religion and Society, Jonathan Edwards and the Great Awakening in Colonial America,” Bill of Rights in Action, 20, no. 4.

[5] William Frankena, Foreword to The Nature of True Virtue, (Michigan: Ann Arbor Paperbacks, 1969), v.

[6] Mark Noll, “Jonathan Edwards, Moral Philosophy, and the Secularization of American Christian Thought,” Reformed Journal, February (1983): 26.

[7] John Bombaro, “Defender of the Faith,” Evangelical Magazine of Wales, March-April (2003): 14-16.

[8] Walter Brian Cisco, Taking a Stand: Portraits from the Southern Secession Movement (Pennsylvania: White Mane Books, 1998), 49.

[9] Ibid., 50.

[10] Ibid., 45-81.

[11] Ibid., 60.

[12] James Farmer, The Metaphysical Confederacy: James Henley Thornwell and the Synthesis of Southern Values (Georgia: Mercer University Press, 1986).

[13] Thomas Law, Thornton Whaling, and A.M. Fraser, Thornwell Centennial Addresses (South Carolinas: Band & White Printers, 1913), 24.

[14] James Henley Thornwell, The Collected Writings of James Henley Thornwell, Volume 4: Ecclesiastical (Massachusetts: Applewood Books, 2009) 405-406.

[15] James Farmer, The Metaphysical Confederacy: James Henley Thornwell and the Synthesis of Southern Values (Georgia: Mercer University Press, 1986), 10.

[16] Walter Brian Cisco, Taking a Stand: Portraits from the Southern Secession Movement (Pennsylvania: White Mane Books, 1998), 50.

[17] Ligon Duncan, “Defending the Faith; Denying the Image – 19th Century American Confessional Calvinism in Faithfulness and Failure,” Ligon Duncan, April 27, 2018.

[18] Edward Sebesta and Euan Hague, The US Civil War as a Theological War: Confederate Christian Nationalism and the League of the South, Canadian Review of American Studies, 32 (2002), 254.

[19] W. Barksdale Maynard, “Princeton and the Confederacy,” Princeton and Slavery, access date: January, 12, 2020.

[20] Sean Wilentz, “Princeton and the Controversies over Slavery,” Journal of Presbyterian History 85 (Fall/Winter 2007): 102-111.

[21] Gordon Arnold, “Jonathan Edwards: Founding Father of American Political Thought,” The Imaginative Conservative, August 26, 2017.

[22] Richard Weaver, “What Can the Southern Tradition Teach Us?,” The Imaginative Conservative, April 25, 2017.

[23] Fred Young, Richard Weaver: A Life of the Mind (Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1995).

[24] C.S Lewis, Preface to Athanasius’ On the Incarnation, (New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2012), 1-2.

[25] Edmund Morgan, “The Puritan Ethic and the American Revolution,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 58, no. 1 (1967): 3-43.

[26] Calvin Coolidge, “The Inspiration of the Declaration,” in The U.S. Constitution: A Reader, ed. Hillsdale College Politics Faculty (Michigan: Hillsdale College Press, 2012), 711.

[27] Walter Edgar, Partisans and Redcoats: The Southern Conflict That Turned the Tide of the American Revolution (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), 127.

[28] Walter Brian Cisco, Taking a Stand: Portraits from the Southern Secession Movement (Pennsylvania: White Mane Books, 1998), 77-81.

[29] Consider also the powerful stories of Puritan missionaries David Brainerd and John Eliot.

[30] Jason Meyer, “Jonathan Edwards and His Support of Slavery: A Lament,” The Gospel Coalition, February 27, 2019.

[31] David Calhoun, The Glory of the Lord Risen Upon It (South Carolina: R.L. Bryan Company, 1995), 72.

[32] Ibid., 72-73.

[33] See recent book, Irv Brendlinger, Social Justice Through the Eyes of Wesley: John Wesley’s Theological Challenge to Slavery (Ontario Canada: Sola Scriptura Ministries International, 2006).

[34] Theodore Appel, Life and Work of John Williamson Nevin (Pennsylvania: Reformed Church Publication House, 1889).

[35] Sarah White, “Sarah and Angelina Grimke,” Modern Reformation, November 26, 2019.

[36] David Field, “John Wesley as a Public Theologian: The Case of Thoughts Upon Slavery,” Scriptura 114, no. 1 (2015): 1-13.

[37] Angelina Emily Grimke, Appeal to Christian Women of the South (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836).

[38] Ibid.

[39] Eugene Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Fatal Self-Deception: Slaveholding Paternalism in the Old South (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[40] “Two Kingdoms and Slavery,” Modern Reformation, September 6, 2013.

[41] Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, Parts I-II, trans. Thomas Whitney (New York: Harper and Row 1974), 168.

[42] Stephen Budiansky, The Bloody Shirt: Terror After the Civil War (New York: Penguin, 2008) 198-200.

[43] Ibid., 259.

[44] Richard Weaver, “What Can the Southern Tradition Teach Us?,” The Imaginative Conservative, April 25, 2017.

[45] John Cotton, The New England Primer (Massacusetts: Edward Draper Printing Office 1777).

The featured images are portraits of Jonathan Edwards (left) by and James Thornwell (right), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and The Southern Presbyterian Review respectively.