Coming soon, as they say, to a theatre near you, but maybe not for long, is A Hidden Life, the latest work of American filmmaker Terry Malick. Not for long, despite positive reviews from Cannes and Toronto film festivals because it is so long like, Malick’s previous works such as A Thin Red Line, Tree of Life, and Badlands, only longer: three hours plus.

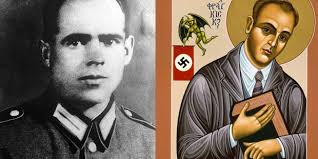

It’s about Hanz Jagerstatter, lately, the Blessed Hanz Jagerstatter, a Catholic conscientious objector in Nazi Germany beheaded in 1943 by the German Army for refusing to serve, and beatified in 2007. It’s also likely to be a frank exposure of how little support the Catholic Church gave him in his resistance.

Peace activist Jim Forest, calls him “one of the least likely persons to question” service to his country, but though I recommend Forest’s free and excellent biography on jimandnancyforest.com, I think he overstates his case. My other readings on those who opposed the Nazis suggests they were oppositional types from the get go. Jagerstatter was always a standout: the illegitimate son of a farm labourer and servant too poor to marry; as a young man he fathered an illegitimate daughter of his own (but always maintained a connection with her and the mother).

All this in the mountain village of Saint Radegund, in Austria hard by its border with Germany. Though a Sunday massgoer, he liked to drink, led a small gang of village youths into fights in area taverns. He went off to make some money in the mines, did so but had a crisis of faith and started sleeping in Sunday mornings. This didn’t last. Jaggermaster returned to his village—on the community’s first motorcycle, met the love of his life, Franziska Schwaninger, and underwent a transformation. His mother had married a successful local farmer who had adopted him, then died, leaving him the farm.

His new wife, as of 1936, was a devout girl from a devout family who soon had Franz reading the Bible daily with her. Villagers later credited( or blamed) her for his devotion and, later, war resistance. But biographer Forest notes that Jaggermaster was earlier contemplating joining a monastery, just as she considered becoming a nun. Given that he had his mother to support, his stepfather’s prosperous farm seemed his destiny, however, not a monk’s habit. He became a daily massgoer and sacristan at the village church. Village opinion seemed to be that Franz became too Catholic, to a degree unseemly in a man. By all reports, they were deeply in love

Though the 100 per cent Catholic village was far off the beaten path, it staged Easter pageants akin to Oberammergau’s drawing pilgrims from Germany. Jagerstatter played a Roman soldier in one in 1933, the last on record.

Nor were villagers oblivious to the rise of Adolf Hitler (born not too far away) and his ambition to annex Austria to Germany, which lay just across the river. In 1933 their bishop, Johannes Gfollner, issued a frank letter read aloud in every church in the diocese. It stated in party, “Nazism is spiritually sick with materialistic racial delusions, un-Christian nationalism, a nationalistic view of religion, with what is quite simply sham Christianity.” Hitler’s obsession with Aryan racial purity, the bishop described as “backsliding into an abhorrent heathenism.”

Prescient but as it turned out, an exception among Austrian bishops.

Other church leaders approved as did many if not most Austrians when Hitler’s German army swiftly occupied their country in 1938. When Hitler ordered a vote to ratify it, everyone in St. Radegund voted for it, except Jagerstatter. But either to protect him or themselves, the village contrived to lose his negative vote. By now the father of three daughters, Jagerstatter had a powerful dream of a glittering train carrying countless multitudes of happy people, especially children, away. Perhaps triggered by reports of hundreds of thousands of Austrian boys lining up for the Hitler Jugend corps, the dream spoke to Jagerstatter of these multitudes: “These people are going to hell.”

He made no secret of his opposition to the Nazis, to Hitler and to the war, when it began. If anyone greeted him with a “Heil Hitler” he would respond with “Phooey Hitler.”

His village protected the dissident at first When the local public health nurse was asked by the Nazi Party organizer in a nearby town to make a list of anti-Nazis, Jagerstatter’s name was on it. Happily for him, the local mail lady opened the health nurse’s outgoing letter and took it to the mayor who destroyed it. When Jagerstatter was ordered to report for military training, and he grudgingly departed, the major got him back by declaring his farm work an essential service.

But this could only work so long. Other men, at first single, but then married, fathers, brothers, sons, were being conscripted. Why not Jagerstatter? He, meanwhile, was hardening in his resolve to resist, boosted by reading between the lines of news reports and by his experience with military training and reports from friends and cousins on the Eastern Front. Special units were rounding up exterminating Jews and gentile villagers.The war was clearly unjust to him: he would not be fighting in defence of the fatherland, clearly, but to conquer other fatherlands, killing other farmers’ sons defending them.

His mother, his new parish priest, and ultimately his bishop (Gfollner had retired), all advised him to join the army, which he might survive, rather than refuse service, bringing certain death. His bishop told him it was not his job to decide on the sinfulness of lawfully-given orders. If the orders forced him to commit a mortal sin, it would damn the officers issuing the order, not him. This Jagerstatter did not accept. Giving his bishop the benefit of the doubt, he told his wife the cleric was probably hiding his real opinion for fear Jagerstatter was a Nazi provocateur. (The Nazis did use agents to extract incriminating statements).

Jagerstatter even tracked down his former parish priest, Father Kartobath,who had been imprisoned for a while for anti-Nazi statements and exiled from the parish when freed. He too told him to accept military service in order to protect his family and ultimately return to them. But the priest later said, “He defeated me again and again with words from the scriptures.”

Franziska supported him. She too, she later admitted, preferred he join up, but believed she owed him her complete support, knowing how seriously he had considered the issue.

A cousin who was a Jehovah Witness also supported Jagerstatter. Several hundred Witnesses would ultimately be executed for refusing military service.

Finally, the stubborn farmer was called up again. After a tearful farewell to his wife and family, he reported for duty, but only to state his refusal to serve. A lengthy imprisonment followed and more attempts to dissuade him. Finally his lawyer persuaded him to offer to serve as a medic. This was a compromise extended to conscientious objectors on the Allied side, but the army rejected the offer. A prison chaplain who had also tried to get him to serve, at last told Jagerstatter of a priest who had been executed for refusing military service. This, the chaplain later recounted, was a big encouragement to the dissenter: virtually the sole encouragement he received from the Church.

Ultimately he was guillotined. And rightly so, was the thinking in his village and newly recreated , postwar Austria.

Jagerstatter’s story remained something of a secret until an American sociologist, writer and pacifist named Gordon Zahn learned of him while researching a controversial book titled German Catholics and Hitler’s Wars: A Study in Social Control, published in 1962 It was condemned by the German and Austrian Churches even before its release. Zahn discovered that after Hitler’s rise to power and crackdown on Catholic dissent, there was virtually no Church opposition to Nazi militarism and to Hitler’s foreign wars.

Individual Catholics and the Church hierarchy ignored the Church’s just war teaching requiring Catholics to oppose unjust wars. The Church did oppose Hitler’s shutting down of Catholic institutions such as seminaries and schools, and its policy of euthanizing the unfit, but faced with war, the Church urged loyalty and patriotism first. In 1962, the Church was making much of what opposition it did show to Hitler, and did not welcome Zahn’s exposure.

However, when Zahn decided to devote his next book to the exception that did not prove the rule, Jagerstatter, the Church was at least open to it. Jagerstatter’s example became an inspiration at the Second Vatican Council to a much stronger support for conscientious objection. Zahn’s book, pointedly titled In Solitary Witness, was published in 1967. Public opinion, even in his village, softened towards him enough to add his name to the cenotaph. His diocese eventually began examining him as a candidate for beatification.

The story raises the question, What if the Church had told all Catholics to resist? The answer seems clear: the German Church was incapable of such an instruction, so thoroughly was patriotism engrained in the German and Austrian psyches. The people in the pew would have simply thought the Church was deranged.

More power, more praise to Blessed Hanz Jagerstatter and his supportive wife, and to other Austrians like Sophie and Hans Scholl, who worked out their moral duty with God’s help only.