FARMING in England is facing a crisis as thousands of farmers have accepted government payments of up to £100,000 to leave their land. The Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) say that their ‘Lump Sum Exit Scheme’, launched in 2022 by Boris Johnson, aims to ‘support farmers in England who wish to leave the industry’.

It has been successful. Last month Defra told me they had received ‘just over 2,200 eligible applications’. Approved farmers who want to throw in the towel have until May 31 of this year to transfer their land, but there is no rule that says it must remain as farmland.

Contrary to a previous statement, Defra said: ‘The scheme itself doesn’t have any specific restrictions – however, we expect that most of the surrendered land will stay as agricultural land.’ Earlier they had said: ‘In return for signing up to the scheme, farmers need to either rent out or sell their land or surrender their tenancy in order to create opportunities for new entrants and farmers wishing to expand their businesses.’

‘Expect’ is the key word here, but is there anything to stop wheat fields being turned into caravan parks, solar or battery farms or any other development?

Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Minister Steve Barclay claims to support the farming community, but his department’s Agricultural Transition Plan 2021 to 2024 is vague. Defra are phasing out subsidies in England which will be replaced by what seem to be performance-based grants. Barclay said: ‘We are investing the money in productivity, innovation and environmental management.’

The report asserts that AI and technology will help improve livestock health and land management and the words ‘biodiversity’, ‘net zero’ and ‘biosecurity’ appear often. It does not refer to cow farts but states that farmers need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from livestock, which presumably means reducing livestock.

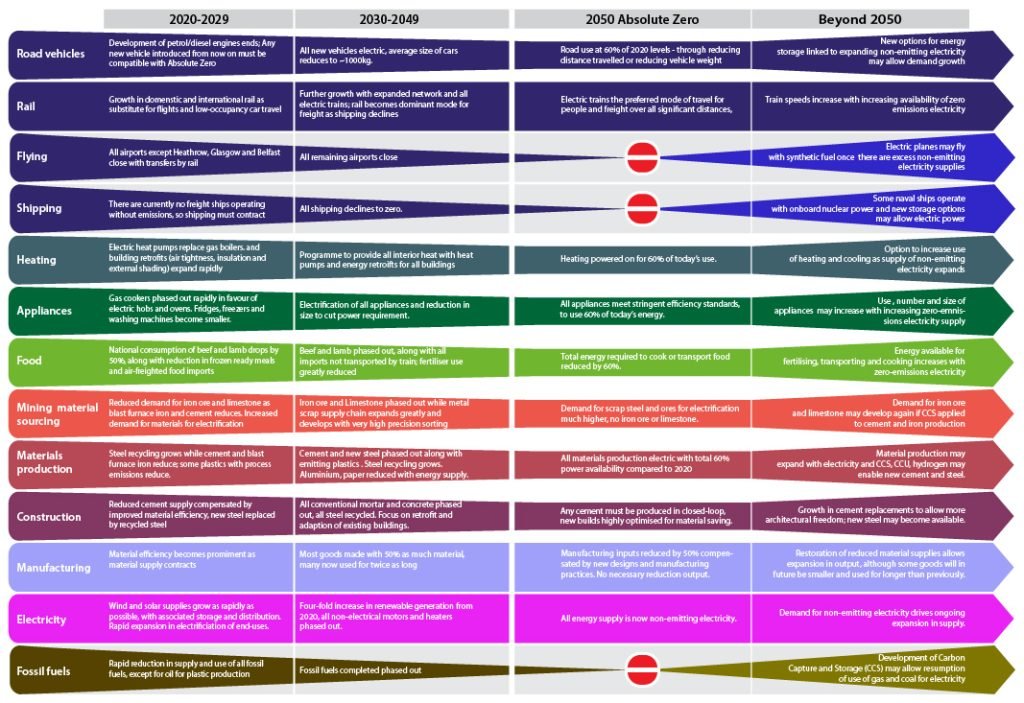

The result is a war of attrition against the farmer as this Net Zero roadmap shows.

It comes from the Absolute Zero report produced by six of our universities, Cambridge, Oxford, Bath, Nottingham, Strathclyde and Imperial College, and funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), a government agency. The research programme goes under the name UK FIRES with the convoluted slogan Locating Resource Efficiency [RE] at the heart of the UK’s Future Industrial Strategy [FIS].

They suggest drastic measures. By 2029 (five years from now), they aim to reduce beef and lamb consumption by 50 per cent. By 2030, they recommend that fertilisers are phased out, by 2050 all beef and lamb production should end and energy used to cook and transport food should be reduced by 60 per cent.

Thus farmers are gradually but surely being sidelined. This is also the subtext of the Sainsbury’s Future of Food Report which is preparing to sell both staple foods and novel foods not produced by farmers. It predicts that from next year, 2025, Sainsbury’s expects to be growing micro and leafy greens hydroponically in store all year round – no farmer needed.

Its ‘vision’is evengrander thanthe government’s, looking forward from 2025, to 2050 and 2169. The report says that in 30 years, jellyfish and other ‘invasive species’ could be found on the fish counter and there could be a ‘lab grown’ aisle, where people can pick up cultured meats and kits to grow meat at home: ‘Meat, as we know it today, could instead start to become a luxury product.’

By 2050, Sainsbury’s expects to be printing meat in store using 3D printing technology. No farmer needed.

Many farms are already struggling. Celebrity farmer Jeremy Clarkson says: ‘I don’t know how anyone can make farming pay. I genuinely haven’t got a clue.’ Last week Farmers Weekly reported that a Kent farmer had given up his dairy herd, despite celebrating 100 years of heritage on the family farm last year. The unnamed farmer said: ‘I’m losing money fairly rapidly on the low milk prices. I am a cattle farmer, I love my cattle, and I’ve spent the last 30 years on the farm trying to sustain the dairy side of things. The milk price means that there’s not the money to invest back into the farm needed for infrastructure improvements. I’ve been told for a long time to get rid of the cows, because storing cars and caravans on the farm will be more profitable. How is that allowable?’

Welsh dairy farmer Steve Evans receives 40-45p per litre for his milk which is used to make cheese, some of which the supermarket Morrisons sell as their own brand. He described Morrisons as one of the fairer paying supermarkets but said: ‘The cheese Morrison’s sell works out at £5 per litre’ – a difference of £4.55.

Currently Tesco’s whole milk sells at £1.06 per litre while a litre bottle of Evian water is £1.15, 9p more than the milk.

A National Farmers’ Union survey – the Dairy Intentions Survey – showed that 10 per cent of respondents intend to stop producing milk by next year, 2025, and that the number of dairy farmers had already fallen by almost 5 per cent in 2023.

Meanwhile, the sharks are circling and see nothing but business opportunities as our food production is transferred from farmers, who know and care about the land but have been victim of so many ‘innovations’ now deemed harmful, to big business and billionaires.

Campaigner Guy Shrubsole, the author of Who Owns England, says that land ownership traditionally dominated by the aristocracy is increasingly the domain of big corporations,who may have invested in land for its tax-saving opportunities, followed by tycoons and the public sector.

This trend is even more evident in the US,where the ‘philanthropist’ Bill Gates, according to the 2022 edition of the Land Report 100, is the biggest private landowner in the US with roughly 275,000 acres of farmland. Gates claims this is to ‘help the agriculture sector become more productive’. He is also reported as saying: ‘I’ll make more money from lab-grown food than all my other investments.’

Gates pushes chemical fertilisers to poor farmers in Africa while backing the Net Zero climate agenda which is against such fertilisers. This makes no sense. In his book How To Avoid A Climate Disaster, he fails to mention that hunger in Africa is largely due to poverty and inequality, not scarcity.

He also promotes the idea that we should eat less meat. Gates is known to be excited about the prospect of fake meat, an initiative backed in the UK by Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and our Food Standards Agency (FSA), who will put forward the option for a streamlined system of testing at their next meeting on March 20. They say a raft of novel food companies are ‘queueing up’ to get involved as they move to ‘slash’ red tape.

Novel food technologies include insect-based food. As of August 2023, four species – the house cricket, the larvae of the grain mould beetle, locusts, and the dried larvae of the flour beetle, have been approved as novel foods by the EU.

Accountants Deloitte said the move could help the UK meet its carbon reduction targets. Deloitte recommended the FSA could allow products such as lab-grown meat to reach the market faster by scrapping existing novel food laws.

Without proper long-term studies and safety checks into how this could affect our health, this is a potential disaster. Yet ‘open- minded’ children are being co-opted to push the ‘let’s eat bugs’ narrative while Wales has the UK’s first edible insect farm: Bug Farm.

The Food Standards Agency’s deputy director of food policy, Natasha Smith, said: ‘The FSA is committed to supporting business innovation in new markets like that of cell-cultivated products, while making sure food is safe and is what it says it is . . . we must balance fast-paced technological advances and industry demands for rapid approval processes with protecting public health.’

Meanwhile, thousands of tractors have taken to the streets in protests across Europe, Ireland, and India, mainly because of unachievable Net Zero targets which could bankrupt many. The Netherlands, a country based on agriculture, led the protests. They are the second biggest exporter of farm produce, yet the Dutch government want them to reduce 95 per cent of their nitrogen emissions, which could force 11,200 farms to close, and 17,600 farmers to significantly reduce their livestock. Six farmers have committed suicide over what they say are unrealistic policies.

In the UK the suicide rate for male farm workers is three times the male national average and every week, three people in the British farming and agricultural industry kill themselves. Young farmers are being encouraged to join the profession but four out of five farm workers under 40 cite poor mental health as the biggest problem they face today.

Farming in England is in decline and jobs are being lost, both regular and casual. According to the government, the total number of people working on agricultural holdings in England was 292,000 in June 2023, a decrease of 2.9 per cent since 2022, while regular workers decreased by 4.2 per cent in 2023 and casual workers fell 11 per cent between 2022 and 2023.

Yet again, profit and green zealcome before people in the most important area of our lives. As Welsh farmer Gareth Wyn Jones said: ‘You might need a doctor or dentist once or twice a year, but you need farmers three times a day.’