In his last moments, Brutus voiced a sentiment about the ultimate tragedy of the virtuous life in those evil days, in which the good was punished and the evil rewarded. This does not make virtue worthless for the individual; it just may place him on the losing side.

[E]veryone knows that some young bucks among the epicures, by continually dining on calves’ brains, by and by get to have a little brains of their own, so as to be able to tell a calf’s head from their own heads; which, indeed, requires uncommon discrimination. And that is the reason why a young buck with an intelligent looking calf’s head before him, is somehow one of the saddest sights you can see. The head looks a sort of reproachfully at him, with an “Et tu Brute!” expression. –Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, Chapter 65 (“The Whale as a Dish”)

[E]veryone knows that some young bucks among the epicures, by continually dining on calves’ brains, by and by get to have a little brains of their own, so as to be able to tell a calf’s head from their own heads; which, indeed, requires uncommon discrimination. And that is the reason why a young buck with an intelligent looking calf’s head before him, is somehow one of the saddest sights you can see. The head looks a sort of reproachfully at him, with an “Et tu Brute!” expression. –Herman Melville, Moby-Dick, Chapter 65 (“The Whale as a Dish”)

Brutus was, as we all know, an honorable man. Or, at least, most of us know it. There have been a few exceptions: Dante (who, to his undying shame, placed Brutus next to Judas Iscariot in Satan’s maw; “Julius Caesar” and “Jesus Christ” can both be abbreviated “J.C.,” but I’m afraid the likeness stops there); Shakespeare’s Mark Antony; and, it turns out, Ralph Waldo Emerson. Consider this an amusing foray into the res publica litterarum that spans several centuries, tongues, and continents, from the Greek tragedians to nineteenth-century America, as well as a reminder of the intellectual dynamism that once existed in the West and may someday exist again.

The outlines of the life of Marcus Junius Brutus are known well enough, as they were delivered to posterity by Plutarch and immortalized in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. A Roman senator alarmed by the tyrannical pretensions of Julius Caesar, he helped to lead a conspiracy that led to Caesar’s assassination on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. Civil war followed, with the opposition led by the Second Triumvirate of Caesar’s grand-nephew Octavian, Marcus Antonius, and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. This opposition eventually prevailed at the Battle of Philippi in October of 42 B.C., upon which denouement Brutus dispatched of himself Catonically.

Sing in me, Muse, and pick it up right around here, more or less, if you would.

Plutarch is not our only ancient source for Brutus’s demise. One of the others, Cassius Dio, tells us in Book 47 of his Roman History that the end went something like this:

Now Brutus, who had made his escape up to a well-fortified stronghold, undertook to break through in some way to his camp; but when he was unsuccessful, and furthermore learned that some of his soldiers had made terms with the victors, he no longer had any hope, but despairing of safety and disdaining capture, he also took refuge in death. He first uttered aloud this sentence of Heracles:

O wretched Valour, thou wert but a name,

And yet I worshipped thee as real indeed;

But now, it seems, thou wert but Fortune’s slave.Then he called upon one of the bystanders to kill him.

Brutus uses his last breath to quote a bit of a lost Greek tragedy (What presence of mind! What an artist dies with him!), by which he figures himself as the great mythological patron saint of mankind. (Cassius Dio isn’t our only source for the quotation; most of it is also found in Plutarch, who quotes it critically at the beginning of On Superstition.)

Plutarch does not report Brutus’s tragic swan-song in his Life of Brutus, which Shakespeare read carefully, and it does not appear in Shakespeare’s play. For a time, the lines are gone but—my my, hey hey—they are not forgotten.

They re-emerge in 1841 in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s First Series essay “Heroism,” where they are attributed to Euripides. Thus Emerson:

It is told of Brutus, that when he fell on his sword, after the battle of Philippi, he quoted a line of Euripides,—’O virtue! I have followed thee through life, and I find thee at last but a shade.’ I doubt not the hero is slandered by this report. The heroic soul does not sell its justice and its nobleness. It does not ask to dine nicely, and to sleep warm. The essence of greatness is the perception that virtue is enough. Poverty is its ornament. It does not need plenty, and can very well abide its loss.

Emerson thinks that Brutus could not have said this because it would diminish his “heroic soul.” He would have made himself smaller by proclaiming the insufficiency of virtue. But insufficiency for what? For himself, Emerson seems to think.

But is that what Cassius Dio meant in his narrative quoted above? At least one of Emerson’s contemporaries thought not: Herman Melville. We happen to know this because we have his annotated copies of Emerson’s Essays, which you can peruse at Melville’s Marginalia Online. (Incidentally, this site is a treasure chest for those who are fascinated by Melvilliana, about which I hope to have more to say anon.)

Melville read Emerson’s First Series in the fourth edition published by James Munroe and Company in Boston in 1847. “Heroism” and “Spiritual Laws” are the essays Melville annotated most heavily in this volume. Here is his comment on the passage in question:

The meaning of the exclamation is here wrested from its obvious import. The struggle in which he was foiled was for mankind, & not for himself.

This is almost certainly correct. Brutus was not renouncing the worth of virtue and courage for the individual, moping shoegazer-like in his last moments. He was instead voicing a sentiment about what Cassius Dio would have us believe Brutus saw as the ultimate tragedy of the virtuous life in those evil days, in which the good was punished and the evil rewarded. This does not make virtue worthless for the individual; it just may place him on the losing side. Advantage Melville.

Given that all that is the case, it is tantalizing to wonder about what Melville would have thought about Dante’s Satanic Brutus. We do have his copy of Dante’s Comedy: He read it in the version translated by the Rev. Henry Francis Cary. Unfortunately, Melville did not comment on Inferno 34 and the Third Triumvirate of Brutus, Casscius, and Judas. But Cary’s note on Brutus is perhaps instructive for how Melville might have thought about him. Cary writes:

Cowley, as conspicuous for his loyalty as for his genius, in an ode inscribed with the name of this patriot, which, though not free from the usual faults of the poet, is yet a noble one, has placed his character in the right point of view—

Excellent Brutus! of all human race

The best, till nature was improved by grace.

One last thing. We can catch a further glimpse of what Melville thought of the noble Brutus vis-à-vis populist, mob-backed Caesarism from a comment he makes on Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. In the second scene of that play, the conspirator Casca says scornfully to Brutus and Cassius, “If the tag-rag people did not clap [Caesar] and hiss him, according as he pleased and displeased them, as they use to do the players in the theatre, I am no true man.” In the margin of his copy, Melville wrote two words: “Tammany Hall.”

This essay was first published here in April 2021.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

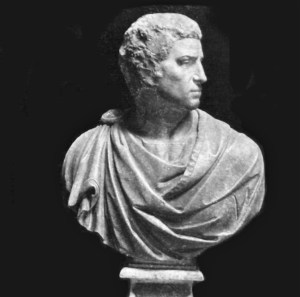

The featured image is “Michelangelo’s Brutus” by Giorgio Sommer (1834-1914) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. It has been brightened for clarity.