The late Steve Masty’s “The Test of the Magi” is a novel that displays a powerful religious imagination and a profound knowledge of the history and cultures of the ancient world, as well as personal experience with the geography and anthropology of the middle east.

The Test of the Magi, by Johannes Bergmann (254 pages, Angelico Press, 2014)

The Test of the Magi is, of course, written by Stephen J. Masty, late of London and Kathmandu, now of Heaven. Steve left us poorer in this world on the Feast of St. Stephen, and his last (published) novel is about what happened on The Epiphany of the Lord, traditionally celebrated in the west as the manifestation of Christ to all peoples. Just as Epiphany shows Christians the universality of Jesus’s life and message, The Test of the Magi gathers much of Steve Masty’s life’s work into one story, and does it in a way that intentionally takes attention away from the author. “To begin with,” said Bishop Fulton Sheen, “have a story where you come out second best.” Johannes Bergmann (a composite lowlander associated with the world of books) makes Steve Masty “second best,” in keeping with the humility that characterized his entire career.

The Test of the Magi is, of course, written by Stephen J. Masty, late of London and Kathmandu, now of Heaven. Steve left us poorer in this world on the Feast of St. Stephen, and his last (published) novel is about what happened on The Epiphany of the Lord, traditionally celebrated in the west as the manifestation of Christ to all peoples. Just as Epiphany shows Christians the universality of Jesus’s life and message, The Test of the Magi gathers much of Steve Masty’s life’s work into one story, and does it in a way that intentionally takes attention away from the author. “To begin with,” said Bishop Fulton Sheen, “have a story where you come out second best.” Johannes Bergmann (a composite lowlander associated with the world of books) makes Steve Masty “second best,” in keeping with the humility that characterized his entire career.

He once wrote in response to an essay on The Imaginative Conservative, “I’ve spent my working life chiefly in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, quite a bit of Africa and the Caribbean, working among Muslims, Christians and Hindus many of whom are traveled and educated but many who are not,” and unlike so many westerners “who are unwittingly decadent and confused by ideology, defecated Reason and make-believe, my friends (even if western-educated) come from ancient and traditional societies and they know wherein their cultural strength lies.” Test of the Magi embodies what he learned from real diversity, not the kind imposed by “free” societies. Steve wrote to me, a year or so ago, that “Afghans are discomfited by the word freedom, fearing it as mere camouflage for license, selfishness and violent chaos.” This, he said, is also true of tribal and traditional cultures around the world.

The epiphany story arrives in Christian culture in Matthew 2:1-12, seen as the fulfillment of promises made in the Old Testament (as in Ps. 70:10 and 60:3-6; Mic. 5:2 and 2 Sam. 5:2 and elsewhere), and from our knowledge of Roman rule, Herod’s regime, Jewish sects, and conditions in Egypt during the years surrounding Jesus’s birth. In a succinct prologue, “Bergmann” provides us with historical and cultural context from which we can re-imagine the journey of the magi. Persia, seized by Parthians a century before Christ, was in a period when its “exquisite culture,” a blend of ancient Classical Persian and Greek Hellenism, was threatened by the coarser and less-educated Parthians, resulting in much court intrigue and dangerous maneuvering for power. Rome, in a frenzy of expansion after the overthrow of the Republic, threatened Persian independence, seeking territory and trade with the east. A massive Roman army led by the greedy Crassus was badly defeated in the Battle of Carrhae (53 BC), setting off a cold war that dominated politics and strategy in the east for decades.

A chief point of contention was the Silk Road. Carrhae came to symbolize for Rome not only imperial humiliation (before the battle, Romans had never seen silk, and legend said that the colorful banners of the Parthian archers confused and bedazzled the mighty Roman legion) but the emergence of a caravan-based trade with the east that changed Rome’s economy forever. The Jerusalem of King Herod stood between the superpowers, a Jewish kingdom whose leader wanted to adopt Roman culture, to the dismay of most of the Jewish sects—an internal problem that went all the way back to the Maccabean revolts against Hellenism. All of this geopolitical, cultural, and economic turmoil was further complicated by a strong messianic religious impulse shared by Jews and Zoroastrian believers. The times were tempestuous, indeed.

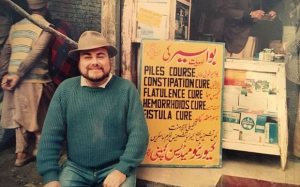

Religious texts say very little about the “wise men” whose journey following a star that seemed to herald a new and mysterious king of the Jews. Strong traditions have given them names—Melchior, Caspar, and Balthazar—and have assigned intriguing roles for them in the great events surrounding the rise of Christianity. A novel such as this requires a powerful religious imagination as well as profound knowledge of the history and cultures of the ancient world, and personal experience with the geography and anthropology of the middle east. Steve Masty is perhaps one of a handful of persons capable of imagining this exciting, nuanced, and sometimes funny story of the magis’ “test.”

The test is actually plural. It is a spiritual journey, organized and conducted by Melchior, an Achaemenid Persian astronomer and philosopher with ties to the highest places in government and the Zoroastrian religion; his devoted student Caspar, a young Parthian destined to succeed the master; and Balthazar, an Ethiopian warrior-king (in exile) who has a great heart and enormous capacity for loyalty. Balthazar is tied into the group by his ancestor, the Queen of Sheba, and the biblical stories of her relationship with King Solomon. Her supposed name was Bilquis, also the name of Melchior’s niece who stows away on the caravan that takes them all to Jerusalem. They are each deeply affected by the journey and especially by their encounter with the Holy Family.

Melchior is a kind of Socrates, at home with reason and faith, an accomplished military strategist who fought in the Battle of Carrhae, and who negotiates court intrigue with calm courage. He is ultimately forced to undergo a trial for his life, caught between the sinister forces of Persian state power and the most profound spiritual test in human history. He also devises a test for the baby Jesus (an ingenious idea mentioned in the journal of Marco Polo): If the new king reaches for the gift of gold, then he is likely a powerful king or emperor; if he is attracted to the frankincense, then perhaps a great religious leader; if the myrrh, a healer. These “were the greatest types of men known to history.”

Caspar tells the story. He adores his teacher (the relationship between professor and student is another test, one that had meaning for Steve Masty’s own life) and meticulously tries to chronicle not only the details of their adventures but to discern the meanings of events as they unfold, even those between heaven and earth. His interaction with Bilquis allows a view into the structure of a traditional society. Because Caspar is so much younger than the other magi, how he accepts the meaning of the test has important implications for the future.

Balthazar is a type of David, except that in the framework of the story we do not see him exercising power. He is strong and athletic, musical and a fine story-teller, able to accept the reality of everyday events more quickly than his friends. At the same time he recognizes the importance of his larger loyalties and duties as the tests challenge him, and he eventually has to decide whether his kingdom is worth having.

They travel together and conspire together, always bearing the burden of being noticed. At one point in Jerusalem, about to have to deal with the nasty tyrant Herod, Melchior remarks: “This is not a town accustomed to visiting Persian academics and their elegant young nieces or well-bred, young Gandharan students or, for that matter, enormous, liquorice-bearing African monarchs.” It may be exactly that quality of their journey that caused Matthew later to write about them, or for (legend, again) the Apostle Thomas to stop off to see Caspar in Persia, on his way to evangelize India.

Their great test, of course, is what they saw in the stable. Steve Masty lets their reactions develop slowly, in both confusion and insight, as the greatest lie or the greatest truth in all of human history; “a great birth and a great death.” And all played out in complicated cultures of real people who could not, as Bilquis put it, “bring the courtroom there or bring Bethlehem here.” Their test, eventually, is for all of us. It is the very test of Epiphany.

Perhaps we can end this part of “Stephen J. Masty, R.I.P.” with another quotation from him—again in a letter to me. More needs to be said about the things he saw, and the adventures he had on his own journey following the star, but for now:

“They [meaning the Afghans and others he has seen] have experienced anarchy in person or close by and they do not like it. Constrained by tradition, family and faith they are comfortable for the most part within their ancient limits, and these are more important to them than economic opportunity or social mobility. When they hear (usually) Americans lecture them on freedom, from college professors to illiterate herdsmen they shake their heads sadly…in limits they find comfort and stability.”

Stephen Masty, Senior Contributor to The Imaginative Conservative, passed away on December 26, 2015 at the age of sixty-one. We pay tribute to him with this essay by John Willson, who was Mr. Masty’s teacher at Hillsdale College and who eventually became Mr. Masty’s student. —Editor

This essay was first published here in January 2016.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is a photo taken by Nina-no. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.