Lawrence Summers, Treasury Secretary under Clinton and economic advisor to Obama, is likely getting himself into trouble once again with the Left.

While president of Harvard, he blurted out the obvious fact that men and women may be different, leading to a vote of no confidence by the faculty of Harvard, and since Biden’s election he has been critical of the president’s economic policies, warning that they were harming the economy.

Well, he’s done it again, this time in an economic paper that provides the explanation for what the Left calls the “vibesession”–the persistent belief by Americans that the economy is much worse than the official statistics indicate.

With higher rates, mortgage payments, car payments, and other credit payments required to finance everyday purchases have risen as well. It is not surprising that this would affect how consumers feel about the economy. 2/N

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) February 27, 2024

No doubt you have seen all the arguments from the pundits that Americans are somehow wrong to believe that the economy sucks for them. Panicked administration officials and MSM folks keep telling everybody that things are great and point at all the economic numbers to prove that to be the case, yet nobody is buying what they are selling.

Summers explains why: the way the numbers have been calculated has changed so much since the 1970s and 80s that they don’t capture the true misery that people are feeling anymore.

The difference? Rises in interest rates, which increase the cost of purchasing goods, if not the goods themselves, are no longer measured as part of inflation.

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed. This has confounded economists, who historically rely on these two variables to gauge how consumers feel about the economy. We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap. The cost of money is not currently included in traditional price indexes, indicating a disconnect between the measures favored by economists and the effective costs borne by consumers. We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era. We then develop alternative measures of inflation that include borrowing costs and can account for almost three quarters of the gap in US consumer sentiment in 2023. Global evidence shows that consumer sentiment gaps across countries are also strongly correlated with changes in interest rates.

People aren’t upset about economic conditions because of undefined “vibes” after all. It turns out that increasing the cost of borrowing increases the cost of living, and if that isn’t measured as part of inflation (it used to be), then the statistics simply miss out on vital data and mislead. It doesn’t even take juking the numbers to come up with an entirely misleading picture; you don’t see what you don’t measure.

Pre-1983, mortgage costs were in the CPI as were car payments pre-1998. Now, price indexes do not include borrowing costs. Thus, when interest rates jumped last year, official inflation did not fully capture the effects it would have on consumer well-being. 4/N pic.twitter.com/xQc2bvpdYI

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) February 27, 2024

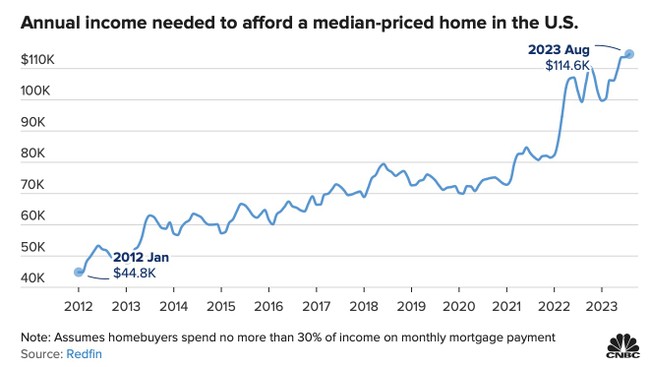

Many people have seen their mortgage payments skyrocket, and anybody who needs a mortgage to buy a home today is absolutely screwed, as the cost of the money they are borrowing is more than double what it was just a few years ago, and house payments are determined by interest rates more than anything else.

This means that the income necessary to buy the same home has jumped dramatically along with interest rates. People will be paying a lot more for the same home, or buying a smaller home in a worse neighborhood for the same money. Assuming a home can be found–people with low mortgage rates don’t want to sell because they have a good rate locked in and don’t want to get a new mortgage at a higher rate.

You can add to this already miserable situation the fact that price spikes stretched budgets for many people, and they started using credit cards at high interest rates to make purchases, adding again to their payments to interest alone.

We also show that the underlying questions in the survey provide direct evidence that concerns of consumers about borrowing costs are at historic highs, surpassed only by the Volcker-era. 6/N pic.twitter.com/zlJo6ter1j

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) February 27, 2024

If you add it all up it turns out that many consumers are in the same boat that people were in at the time Paul Volcker was crushing inflation in the late 70s and early 80s. If we measured inflation the same way we did back then, the misery index would begin to look much more like it did back then.

We show that if we make an effort to reconstruct the CPI of Okun’s era—which would have had inflation peak last year around 18%, we are able to explain 70% of the gap in consumer sentiment we saw last year. 8/N pic.twitter.com/ZuXcck68LK

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) February 27, 2024

You can see how not measuring the price of money dramatically changes things. If you don’t add in the borrowing costs, you completely miss what can be a huge, at times dominant part of the actual price of a good. Even modest changes in interest rates can dramatically alter the final price of a good, and we have seen much more than modest changes in interest rates.

U.S. economy faces 1970s-style stagflation as inflation sticks around https://t.co/0zNQAGG8Fd

— MarketWatch (@MarketWatch) March 16, 2024

It doesn’t even require a conspiracy theory to explain how even innocent changes in the statistical measures of phenomena like inflation can dramatically change our perceptions and make apparently similar measurements wildly different in reality. The “Misery Index” of today measures an entirely different set of data than that when it was invented. Different data is collected and analyzed, meaning that today’s Misery Index doesn’t capture what it once did.

Whether the changes to how inflation is measured were done innocently or were part of a strategy to bury inconvenient data is, in the end, not relevant to consumers. We know what we experience, and since most people depend on borrowing money for big purchases, the cost of money can’t be ignored. For people living in a cash economy, inflation has subsided quite a bit; for people who pay mortgages or are looking to buy a house, not so much.

No doubt Summers’ analysis will annoy a lot of people, not because it is a partisan explanation, but because it isn’t. It makes sense, explains an unexplained phenomenon, and is an inconvenient truth.