John Ioannidis is one of the ten most cited scientists globally and is generally recognized as one of the best.

His best-known work is Why Most Published Scientific Results Are False, which has helped revolutionize how people think about the incentives in science. A researcher at Stanford who is a member of 5 departments, including Medicine, Epidemiology, Statistics, Biomedical Data Science, and Innovation in Research, when he publishes, he tends to get the attention of many.

So when he co-authored a paper titled “Is society caught up in a Death Spiral? Modeling societal demise and its reversal,” I immediately decided to read it. The primary author is Michaéla C. Schippers, and Matthias Luijks is a contributing author. I refer to Ioannidis mainly because his is the most recognizable name rather than because he is the only or primary author.

Fresh Ioannidis co-authored paper. How relevant to the the present moment in all of our institutions. Must read. pic.twitter.com/zhAC0e21iA

— J.D. Haltigan, PhD 🏒👨💻 (@JDHaltigan) March 24, 2024

If you have a taste for social science research, by all means, dive in, but I warn you that if you have an allergy to academic papers filled with citations (I read innumerable ones in grad school), it will be a bit of tough sledding.

Not because the concepts are difficult to grasp–take out the citations and the argument is clear enough. But there is a reason why all those Harvard profs plagiarize–citing things can be a drag. It must be done, of course, but it takes as much work (or more) than expressing your argument.

You can’t fault the argument for failing to tackle a tough subject: what makes societies fall and how a failing society might recover before it is too late to avoid disaster.

The topic is fascinating in itself but is particularly relevant because Ioannidis thinks the West may be in a death spiral, and suggests ways to reverse this trend.

Just like an army of ants caught in an ant mill, individuals, groups and even whole societies are sometimes caught up in a Death Spiral, a vicious cycle of self-reinforcing dysfunctional behavior characterized by continuous flawed decision making, myopic single-minded focus on one (set of) solution(s), denial, distrust, micromanagement, dogmatic thinking and learned helplessness. We propose the term Death Spiral Effect to describe this difficult-to-break downward spiral of societal decline. Specifically, in the current theory-building review we aim to: (a) more clearly define and describe the Death Spiral Effect; (b) model the downward spiral of societal decline as well as an upward spiral; (c) describe how and why individuals, groups and even society at large might be caught up in a Death Spiral; and (d) offer a positive way forward in terms of evidence-based solutions to escape the Death Spiral Effect.

Much of the paper is developing a theory of how death spirals develop, and the rest is about potential ways to use management theory to help break the vicious cycle. But underlying the entire effort is a recognition that recent failures in policy are indicative of a societal sickness that threatens our civilization.

Needless to say, I am sympathetic to this diagnosis and have said so often enough.

Ioannidis doesn’t date the societal problems to the pandemic per se, but points to the decision-making as indicative of a broken policy-making apparatus that had been making serious errors for a long while.

While the period before the COVID-19 crisis may have been characterized by relative policy underreaction to complex social problems, also referred to as “wicked problems,” such as hunger and poverty (Head, 2018; Head B.W. 2022), the current times may be characterized by overreaction to certain problems. The COVID-19 crisis seemed to be characterized by groupthink and escalation of commitment to one course of action, at the expense of other possible solutions (Joffe, 2021; Schippers and Rus, 2021). Initial low-quality decision-making was followed by decisions that made things worse (Joffe, 2021; Schippers and Rus, 2021). The sheer scale and severe disruption caused by these policies has increased inequalities (Schippers, 2020; Schippers et al., 2022), an important marker of societal decline (Motesharrei et al., 2014).

The paper specifies a set of conditions that mark societal decline. In social science-speak, the paper “operationalizes” the term to include measurable variables. I will forgo giving all that to you because if you like, you can read the paper.

But the description of what happened during COVID and the diagnosis for why it did are worth paying attention to. Ioannidis et al. didn’t just say “Hey, they screwed up!” They explained why they screwed up and how the systemic errors point to an unhealthy policy-making dynamic that threatens everything.

For the current review, we feel that the handling of the COVID-19 crisis may have been an example of overreaction making use of non-pharmaceutical interventions that accelerated existing societal problems, such as inequalities (Schippers, 2020; Schippers et al., 2022). Most countries opted for very similar solutions, with forced lockdowns and aggressive restrictions. Countries that chose a different course of action were highly criticized (Tegnell, 2021). Many countries eventually faced excess mortality rates that were highly unequal across groups, exacerbating preexisting inequalities (Alsan et al., 2021; Schippers et al., 2022). Over-reaction was fueled by (unreliable) metrics (Schippers and Rus, 2021; Ioannidis et al., 2022) and groupthink, resulting in irrational or dysfunctional decision making (Joffe, 2021; Hafsi and Baba, 2022). Furthermore, emotions during crises tend to run high, escalating the risk of harmful overreaction both by policy makers and the general public (Sunstein and Zeckhauser, 2010). Governments may suffer from an action bias, a tendency to take action whether it is needed or not, including excessive actions (Patt and Zeckhauser, 2000) despite information that the policies may do more harm than good (for reviews see Joffe and Redman, 2021, Schippers and Rus, 2021; Schippers et al., 2022). Unnecessary crisis response as a form of policy overreaction may sometimes occur as a way to shape voters perceptions of a decisive and active government (Maor, 2020). Excessive action and exercise of control over societal structures, e.g., public health, may enhance centralization of power and decision-making, and authoritarianism (Berberoglu, 2020; Desmet, 2022; Schippers et al., 2022; Simandan et al., 2023). When governments make use of mass media to spread negative information, a self-reinforcing cycle of nocebo effects, “mass hysteria” and policy errors can ensue (Bagus et al., 2021). This effect is exacerbated when the information comes from authoritative sources, the media are politicized, social networks make the information omnipresent (Bagus et al., 2021), and dissenting voices are silenced (Schippers et al., 2022; Shir-Raz et al., 2022). This may lead to a vicious cycle of ineffective dealing with crises, low-quality decision-making and dysfunctional behavior, intensifying the current crises and leading to new ones, and eventually societal decline and even collapse.

Sound familiar? Now ask yourself whether the same dynamic is at work with the elite reaction to Trump, which follows exactly the same pattern. Even if you think Trump is bad for the world, is the elite reaction and propaganda campaign in proportion to the harm that he could possibly do? All that “threat to democracy” and “insurrection” BS is being used to justify an overreaction that is threatening our society.

In other words, the out-of-proportion reaction to Trump threatens everything that it claims to be protecting. Kicking the leading candidate off the ballot is what Maduro just did in Venezuela, and they are trying to do the same here. As well as bankrupt him. And put him in jail. And silence his supporters (Chuck Todd/NBC, anyone?)

It is exactly the same phenomenon. Elite hysteria.

An important problem that the US are dealing with is not only the growth of economic inequalities, which are huge, but also political division of society, military overreach and financial crises (Peters et al., 2022). The power elite have positions that enable them to make decisions that have far-reaching consequences for ordinary men and women. They are also often in a position that they can influence politicians an pressure groups (Mills, 2018). At the same time, some authors refer to a netocracy, a global upper-class with a power-base derived from technological advantage and networking skills. The new underclass, or masses, is called consumtariat, whose main activity is consumption, regulated by those in power (Bard and Söderqvist, 2002). Generally, what becomes apparent in the literature is that rising inequalities, which represent basically a growing divide between elite and masses, are an important and potentially reversable marker of societal decline (Moghaddam, 2010; Diamond, 2019).

The pandemic response has led to the single-largest mass shift of wealth in human history. The middle classes have been immiserated, while the wealthy saw their resources expand by trillions of dollars. Small businesses were killed, while tech companies and mega-retailers benefited, especially Amazon.

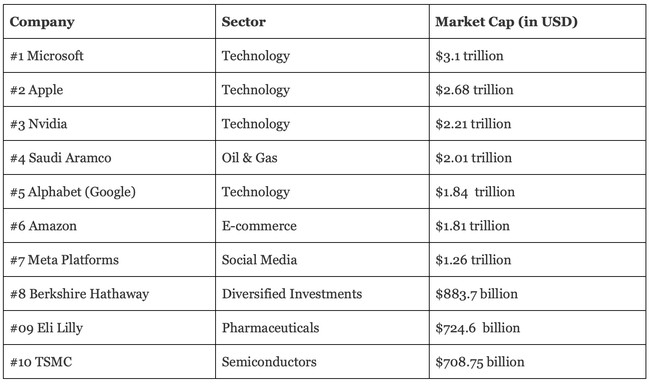

Currently, 7 out of the top 10 companies in market capitalization are technology-related. While Microsoft may do wonderful things, it is hard to say that its contributions to overall human well-being is reflected in its leading position. I love my Apple products, but…really?! Saudi Aramco at least produces a product without which society couldn’t exist.

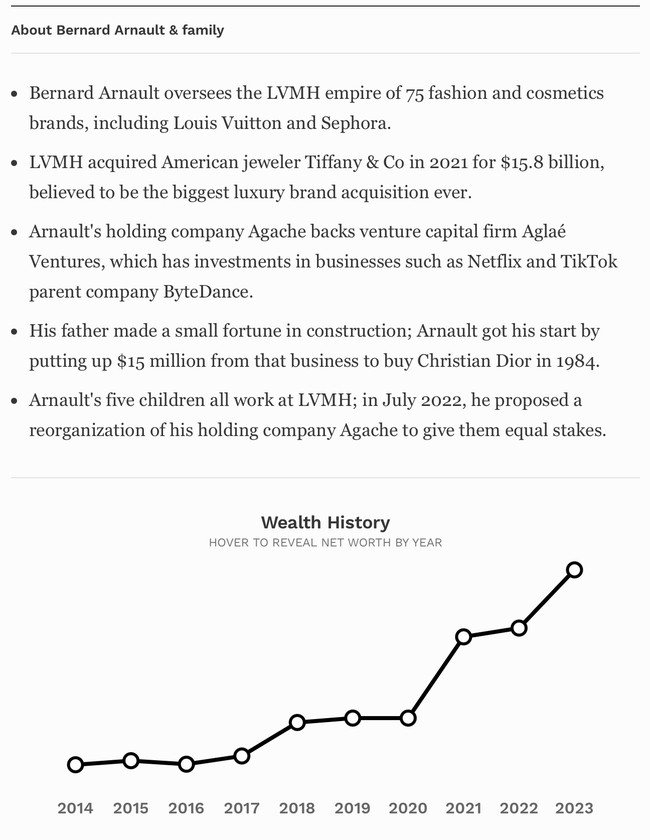

Pandemic-era policies shifted enormous resources to the world’s wealthiest. Currently, the wealthiest man in the world owns Hennessey and Louis-Vuitton, along with other luxury brands.

Notice the jump that began in 2020? It is duplicated among all the billionaires.

The rise in prominence of the WEF and other transnational entities to the point that they can command the attention of every world leader, the explosion of power at the WHO and UN, and the burgeoning censorship complex all fit Ioannidis’ diagnosis.

None of this is healthy, and all are directly related to the steady stream of moral panics that grip our society. COVID, DEI, alphabet ideology, the outsized reaction to Israel’s war are all characterized by elite-driven hysteria.

Action bias, along with escalation of commitment and sunk cost fallacy may have played a role in the suboptimal decision-making processes surrounding the COVID-19 crisis (Schippers and Rus, 2021). Combined with the (in hindsight) overestimation made by experts of the expected infection fatality and of the buffering effects of several aggressive measures (Chin et al., 2021; Ioannidis et al., 2022; Pezzullo et al., 2023) led to a disastrous chain of self-perpetuating decision-making (Magness and Earle, 2021; Murphy, 2021). Instead of dialing back, the general political climate and response doubled down on the measures and on defending a narrative in their support, leading to a Death Spiral of low-quality decision making and serious consequences.

The paper is long (as you would assume, given that my precis itself is long), and well worth a read if you can deal with the academese that creeps in.

But the bottom line is this: society is in a death spiral, and unless we stop it now, collapse is coming.

I told you so.