Going back to the first principles of the Founding, one finds that the Founders talked unceasingly about rights. Rights language became a critical part of the cultural landscape when James Otis delivered his oration on the nature of rights, the common law, and the natural law.

Feel free to call me a conservative (I won’t object), but my response to a crisis is always to go back to first principles. I feel like I’ve been going back to first principles repeatedly over the past eleven months. Lockdowns, riots, more lockdowns, more riots, election confusions, more lockdowns (remember, I live in Michigan—no state has been more locked down) and—lo and behold—another riot. This last one, though, was the real doozy. Since 1968, those of us not on the left have been able to blame civil unrest on the left itself. Those days, it seems, have finally ended. Regardless, let’s return to first principles.

Feel free to call me a conservative (I won’t object), but my response to a crisis is always to go back to first principles. I feel like I’ve been going back to first principles repeatedly over the past eleven months. Lockdowns, riots, more lockdowns, more riots, election confusions, more lockdowns (remember, I live in Michigan—no state has been more locked down) and—lo and behold—another riot. This last one, though, was the real doozy. Since 1968, those of us not on the left have been able to blame civil unrest on the left itself. Those days, it seems, have finally ended. Regardless, let’s return to first principles.

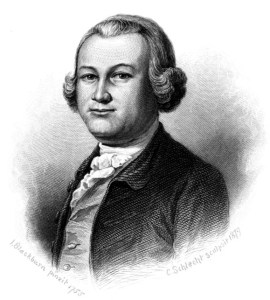

In particular, since the Capitol Hill unrest, I’ve been thinking about the nature of rights and duties. Going back to the first principles of the Founding, one finds that the Founders talked unceasingly about rights. While rights language appears before the 1760s, it becomes a critical part of the cultural landscape in February 1761 when James Otis delivered his five-hour oration on the nature of rights, the common law, and the natural law. The basis of the argument came from Otis’s denial of the writs of assistance—which had, in violation of the common law, allowed for an open-ended search and seizure by government agents. They did not have to prove guilty, but merely presume it. They did not have to have probable cause, only instinct. Thus, armed with the writs of assistance, they could search any man’s property for any reason at any time and without impediment.

Although we do not know exactly what Otis said that day, we have some good indications from his writings following that speech. “I say men, for in a state of nature, no man can take my property from me, without my consent: If he does, he deprives me of my liberty, and makes me a slave,” Otis argued. “If such a proceeding is a breach of the law of nature, no law of society can make it just—The very act of taxing, exercised over those who are not represented, appears to me to be depriving them of one of their most essential rights, as freemen; and if continued, seems to be in effect an entire disfranchisement of every civil right.” While God demands that men govern themselves, the laws of nature and the common law prevent one man from controlling another man. Slavery, thus, in any form is forbidden, whether it be chattel slavery or the taxation of a person without his consent.

Otis’s speech riveted the American colonies, and many revolutionaries—such as the brilliant John Adams—claimed that the revolution began at that moment in February 1761.

But Otis was a flame of fire!—with a promptitude of classical allusions, a depth of research, a rapid summary of historical events and dates, a profusion of legal authorities, a prophetic glance of his eye into futurity, and a torrent of impetuous eloquence, he hurried away every thing before him. American independence was then and there born; the seeds of patriots and heroes were then and there sown, to defend the vigorous youth, the “non sine Diis animosus infans.” Every man of a crowded audience appeared to me to go away, as I did, ready to take arms against writs of assistance. Then and there was the first scene of the first act of opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain. Then and there the child Independence was born. In fifteen years, namely in 1776, he grew up to manhood, and declared himself free.

Yet, Otis himself seems to have believed strongly in a decentralized British commonwealth, not an independent America.

The sum of my argument is, That civil government is of God: That the administrators of it were originally the whole people: That they might have devolved it on whom they pleased: That this devolution is fiduciary, for the good of the whole; That by the British constitution, this devolution is on the King, lords and commons, the supreme, sacred and uncontroulable legislative power, not only in the realm, but thro’ the dominions: That by the abdication, the original compact was broken to pieces: That by the revolution, it was renewed, and more firmly established, and the rights and liberties of the subject in all parts of the dominions, more fully explained and confirmed: That in consequence of this establishment, and the acts of succession and union his Majesty GEORGE III. is rightful king and sovereign, and with his parliament, the supreme legislative of Great Britain; France and Ireland, and the dominions thereto belonging: That this constitution is the most free one, and by far the best, now existing on earth: That by this constitution, every man in the dominion is a free man: That no parts of his Majesty’s dominions can be taxed without their consent: That every part has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature: That the refusal of this, would seem to be a contradiction in practice to the theory of the constitution: That the colonies are subordinate dominions, and are now in such a state, as to make it best for the good of the whole, that they should not only be continued in the enjoyment of subordinate legislation, but be also represented in some proportion to their number and estates, in the grand legislature of the nation: That this would firmly unite all parts of the British empire, in the greatest peace and prosperity; and render it invulnerable and perpetual.

In other words, for Otis, the empire worked best when it was not an empire, but a sort of libertarian commonwealth, decentralized but interdependent.

While the analogue isn’t perfect, one can make a similar argument about the current state of the United States. There is no need for us to break apart, but there is a great need for us to behave in a fashion that respects those parts of the country that are different from our own. We do not need to break apart the country, but we do need a sort of libertarian commonwealth, decentralized but still interdependent. As it is, we have placed far too much power in Washington, far too much power in the presidency, far too much power in the Supreme Court, far too much power in Congress, and, especially, far too much power in the bureaucracy.

Now, more than ever, it’s time to return to first principles.

This essay was first published here in January 2021.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is an engraving of James Otis (1879) by C. Schlecht and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.