Many in our society consider religion merely an instrument of power, and they believe that the “correction” of inherited beliefs and practices can be forced upon the unwilling. But there’s an enormous difference between people who choose the real common good and people forced to submit to a state ideology.

When I went into the kitchen yesterday morning to get some coffee, my wife looked up from the sofa and said, “You have to listen to this.” It was an op-ed piece about the Dalai Lama by Walter Russell Mead in Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal, and she just read me one sentence: “Beijing has declared that any attempted reincarnation must ‘comply with Chinese laws.’ ” I laughed out loud. The struggles of Tibet aside, the question of whether the Dalai Lama is actually “an emanation of the bodhisattva of compassion” even farther aside, it struck me as another comical example of state overreach (not that there’s anything funny about China’s ambitions). Solemn Beijing was entirely at odds with what our freshmen have just undergone in their 21-day backpacking expedition, which was a full-bore encounter with realities outside their control.

When I went into the kitchen yesterday morning to get some coffee, my wife looked up from the sofa and said, “You have to listen to this.” It was an op-ed piece about the Dalai Lama by Walter Russell Mead in Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal, and she just read me one sentence: “Beijing has declared that any attempted reincarnation must ‘comply with Chinese laws.’ ” I laughed out loud. The struggles of Tibet aside, the question of whether the Dalai Lama is actually “an emanation of the bodhisattva of compassion” even farther aside, it struck me as another comical example of state overreach (not that there’s anything funny about China’s ambitions). Solemn Beijing was entirely at odds with what our freshmen have just undergone in their 21-day backpacking expedition, which was a full-bore encounter with realities outside their control.

To declare what the Chinese declared is a little like Wyoming Catholic College saying that, from now on, the timing of storms, the placement of boulders after landslides in the mountains, and the behavior of wild animals must “comply with the rules of Wyoming Catholic College.” If the Romans in Jerusalem had just been as savvy as the Chinese, they would have insisted that the triumph over death in the Resurrection comply with Roman law.

It’s almost impossible to keep from coming back to the theme of power over God and nature, because it seems so distinctively modern in the pejorative sense of that word—that is, modern in thinking that the complex-of-things-formerly-

“We relate to man-made environments as gods to our creation, as masters to our slave,” writes Dr. Jeremy Holmes, explaining the rationale behind our Outdoor Leadership Program. On Monday, as part of their orientation to WCC, the freshmen read Dr. Holmes’s addendum to the Philosophical Vision Statement and are divided into four seminar groups to discuss this text that distinguishes between the manmade world and the natural one. Dr. Holmes emphasizes the stark difference. “Those who live all of their lives in the posture of gods may understandably come to think of themselves as lords of all, unaccountable to anyone and free to dispose of the world as they will. What man has made is, by that very fact, lower than man and subject to him.” The natural world, on the other hand, cannot be ascribed to human making. The Grand Tetons sublimely touch upon the mystery of being itself; so does the intricate architecture of a dragonfly’s wing.

Strangely, the question at large these days in secular culture is whether God and nature are themselves man-made. The flat assumption of Beijing is that any religion is merely an ideology, a mode of power; it makes perfect sense within such atheistic thinking to insist that future reincarnations of the Dalai Lama comply with Chinese law. Beijing’s attitude toward the Catholic Church follows the same logic. As an article in the South China Morning Post put it last year, “President Xi Jinping has launched a sweeping campaign to ‘sinicise religion,’ which demands all religious groups practice their faith in a Chinese way.” Enough said.

With high technological rigor, the Chinese are attempting the kind of total indoctrination—erasing any distinction between state aims and personal desire—whose possibility has fascinated and appalled Western thinkers from Plato to Orwell. As Walter Russell Mead puts it in his commentary on the Dalai Lama, “The technology of surveillance, including biometrics, has given Chinese authorities unprecedented hard power in places ranging from Beijing to the Han Chinese heartland. China’s rulers are in a position to know more about what their subjects do, where they go, and what they think than any rulers in the history of the world.” It’s reasonable to ask why. It does not bode well.

In this country, we are still a few removes from the total surveillance state that China has already achieved, though there are other kinds of unnerving developments going on here—for example, what Jordan Peterson experienced recently.[*] (Our technology policy at WCC looks wiser than ever.) But many in our society hold underlying modern assumptions in common with Beijing: they consider religion merely an instrument of power, and they believe that the “correction” of inherited beliefs and practices can be forced upon the unwilling.

There’s an enormous difference between people who choose the real common good and people forced to submit to a state ideology. In a famous passage of Paradise Lost, Milton’s God acknowledges that He could have created Adam and Eve without freedom. But what would there be to praise? “Not free, what proof could they have given sincere / Of true allegiance, constant faith or love, / Where only what they needs must do appeared, / Not what they would?” True communities like ours are built upon trust of each other and love of God. We are grateful here at Wyoming Catholic College to provide an education that acknowledges, first and last, that reality has never been ours to invent. That recognition itself, as Dr. Holmes says in his piece on the outdoor program, opens us to wonder, which is not available to those who think they made the world.

Republished with gracious permission from Wyoming Catholic College‘s weekly newsletter.

This essay was first published here in August 2019.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

* Peterson, Jordan. “I Didn’t Say That.” Jordan B. Peterson, 22 August 2019.

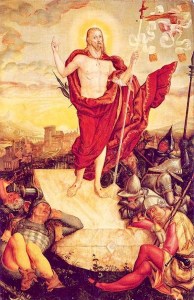

The featured image is “Der-Auferstandene” (1558) by Lucas Cranach (1472-1553), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.